The Invaders

Air Date: Week of April 10, 2015

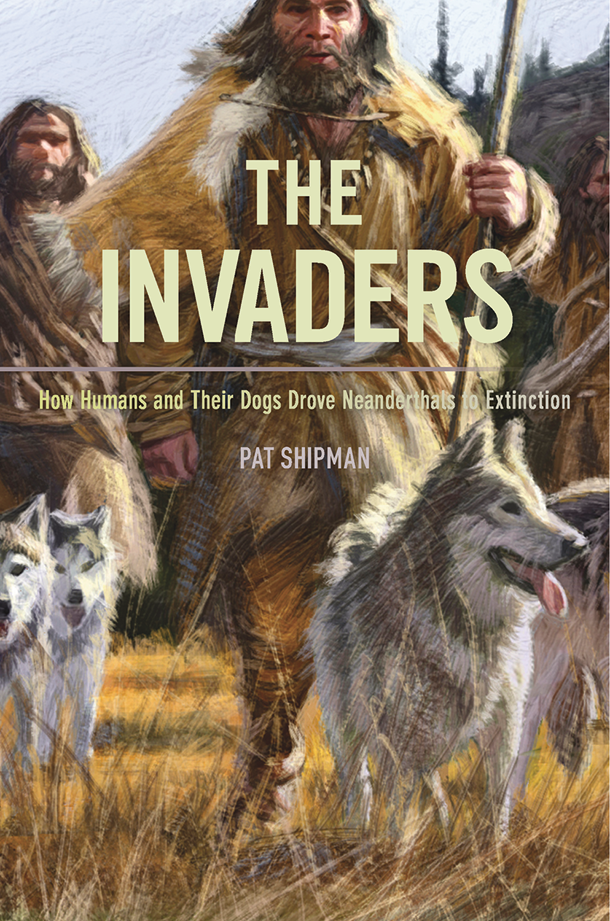

Pat Shipman, a retired Professor of Anthropology at Penn State, used new anthropological findings to argue in her book The Invaders that modern humans and their canids drove Neanderthals to extinction. (Illustration: © 2014 Dan Burr)

There are many theories as to why our ancestral cousins, the Neanderthals, died out: everything from climate change to lack of intelligence. Pat Shipman, a retired Professor of Anthropology, has a new theory, explained in her book The Invaders, and in conversation with host Steve Curwood. She argues that modern humans, the most successful invasive species of all time, can thank our canine companions for this competitive edge over Neanderthals.

Transcript

CURWOOD: And now, a provocative view of modern humans.

SHIPMAN: We have been the most successful invasive species as far as I can think of. We have moved out of the place where we evolved, in Africa, into Europe and Asia and now the Americas, and just about every place that it would be possible to live, and we're doing astonishingly, or maybe appallingly, well.

CURWOOD: That’s Pat Shipman, a retired Professor of Anthropology at Penn State University, whose new book "The Invaders" makes the case that our partnership with domesticated wolves gave us a competitive edge over Neanderthals, hastening their extinction. This is a different hypothesis from those previously put forward for why Neanderthals died out, and new techniques of carbon dating suggest this all happened both earlier and faster than previously believed. Pat Shipman, welcome to Living on Earth.

SHIPMAN: Thank you for the invitation.

CURWOOD: So this is a new concept, a new hypothesis. What did we used to think the reason was that Neanderthals went extinct?

SHIPMAN: The dominant theory until lately has been climate change. There certainly was a rapidly shifting climate starting about 45,000 years ago, and it went from colder and dryer to warmer and wetter and back again pretty rapidly by a geological time scale. And it certainly had an impact on vegetation, on the other animals, so of course it had an impact on Neanderthals and modern humans. However, Neanderthals had lived through several episodes like this before, that were as cold and dry as what happened in that crucial time period of overlap. So there's no obvious reason why they would have been unable to cope with it and modern humans would have been less hindered, except, of course, we had dogs. Another one was, oh, they're just too stupid, and we have so much evidence now of some very sophisticated things they did, that I don't think that holds up very well. They had survived for hundreds of thousands of years. They may not have been as adaptable, they may not have been as good at communicating with dogs, but they weren't the old-style Neanderthal saying "Ugg". That's kind of a slander against them. They were better than that. So I think there's something wrong with many of the theories that have been put forward by now that we owe to the new dating improvements and we owe to these very sophisticated techniques for identifying dogs as dogs.

CURWOOD: So, what has changed now that we have the technology that gives us a more accurate view, at least we think we have a more accurate view, of when things happened? What's different now about what happened to the Neanderthals and us for that matter?

SHIPMAN: OK, we now would say based on the dates we have at present that modern humans got into Eurasia perhaps 42,000 years ago, maybe 1,000 or 2,000 years earlier than that. Neanderthals had already been there for a couple of hundred thousand years. What used to be believed with fair reason because that's what the technology of the time told us was that Neanderthals then hung on until about 25,000 years ago when they went extinct, so that would be a 20,000 year period of overlap. The new dates now tell us that 20,000 years may only have been 2,000 years so it's a pretty rapid event after the arrival of modern humans.

A Neanderthal skull (Photo: Paul Hudson; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So some 40,000 years ago, 42,000 years ago you suggest Neanderthals start to go extinct just as little as 2,000 after modern humans show up in Europe. What happened?

SHIPMAN: To try to answer this, I took a look at what we know about the effects of invasive apex predators, that is top predators. And I turned to events in Yellowstone National Park in the American west where 31 gray wolves were released into the park. Now, there had not been gray wolves in Yellowstone National Park in the immediate area since the very early 1900s. So the Yellowstone National Park that most of us have grown up with is actually an impoverished ecosystem because we took out the top predator or certainly one of the top predators. When they came back in to rebalance and restore the original ecosystems some very fascinating things happened. Coyotes, which are of course doggy animals not that different from wolves except primarily in size, got absolutely hammered. The overall population of coyotes in the park dropped by 50 percent. So what that tells us in a very simple analogy is when a new apex predator comes then it strains the whole ecosystem and the predator that's already there that is most like the new one is the one that feels the competition most keenly.

CURWOOD: Oh my God. So, humans, sort of like a well financed person in Manhattan, just simply bid the ecological space up out of sight for the Neanderthals, it sounds like.

SHIPMAN: Yes, basically that's it. It was already a crowded ecosystem with a lot of very able predators and very shortly after we arrived Neanderthals went extinct and you can then tick off different species different kinds of predators and even different kinds of prey that eventually went extinct.

CURWOOD: So what's fascinating about your book is it you say that modern humans move into the turf of the Neanderthals and start to push them out of the way as top predator but physically of course the modern human was perhaps smaller and had a lot less strength that the Neanderthal, and you also say that probably intelligence was comparable. So you came up with a rather interesting hypothesis as to why humans win this battle of being the top predator. What's the core of your idea here and why are wolves, or rather dogs involved in that?

SHIPMAN: In 2009, a Belgian colleague of mine, Mietje Germonpre and group of international researchers worked out a way to tell from the fossils alone what was a wolf and what was a dog. And then once they had established that the system worked, start throwing in canid skulls from the fossil record. One of the first groups of canids they looked at involved a skull from Goyet cave in Belgium and it turned out to classify as a dog. So they had the skull redated with the new dating techniques. It came out to be almost 33,000 years old; it might be as much as 37,000 years old. This was at least 20,000 years older than anybody had expected and as they continued to use this system they found more and more and more of these animals that I call ‘wolf dogs’. And they now have identified over 40 individual wolf dogs from various sites in Central and Eastern Europe. And these turn up very, very shortly after Neanderthals went extinct think so I'm willing to say what that this was a major advance in lifestyle and hunting efficiency for modern humans and all of these wolf dogs turn up in modern human sites. There are none in Neanderthal sites.

Modern humans and early wolf-dogs teamed up and out competed Neanderthals, driving them extinction in possibly as little as 2,000 years. (Illustration: © 2014 Dan Burr)

CURWOOD: So modern humans had domesticated the wolf and turned the wolves into hunting buddies, your book says.

SHIPMAN: Yes, basically. I don't want people to be thinking about hunting dogs now, which have had a long time to evolve and be especially bred for different tasks involved in hunting. But wolves are of course hunters. They are pack hunters. They're used to cooperative hunting, and what I think was going on was that modern humans managed to get at least a somewhat domesticated wolf dog that could live with them, could hunt with them, providing benefits to both partners, but that made them a much more efficient hunter than they had ever been before.

CURWOOD: Explain to me what the deal was for the wolf dog and what the deal was for the human.

SHIPMAN: For the wolf dog there would be several significant advantages. What I believe happened is that wolf dogs would do what wolves often do with big prey, that is they'd isolate one individual, they'd surround it, they'd drive it away from the others and hassle it, threaten to attack it, maybe take a good chunk here and there until the prey animal was exhausted, couldn't run anymore, but was still feisty. Now a wolf would then have to go in and pull that animal down. That's where they get hurt. However, if you have modern humans working with you, at that point the modern humans kill the animal with a bow and arrow or a spear with a spear thrower. Nobody gets hurt and they can actually prevent other predators from coming in and stealing it. But they can share the task. So you get more prey, you get it faster; you get it with less risk and less energy expenditure.

CURWOOD: So if humans and Neanderthals had similar skills and intellect, how come Neanderthals didn't domesticate the wolves?

SHIPMAN: I don't have an answer based on evidence. I can give you some answers based on speculation. Neanderthals appear to have been less adaptable than humans. Another issue is there is a signal that humans can give that is very important in cooperative hunting. We read direction of gaze. We use that without even thinking about it to make predictions about what another person is going to do. We are the only primate in the world that have white sclera, that is, the whites of our eyes surrounding the dark colored iris. If I look at you and I want to signal you something about the animal we’re hunting together I can look at you, look over at the animal, or look at the direction I'm going to go, look at the bush I'm going behind and you can read that from a considerable distance, I don't have to shout and wave my arms and do all kinds of obvious things. Dogs are very, very, very good at reading direction of gaze. Wolves for a nondomestic canid are rather good at reading direction of gaze, but in fact, they're not looking to people for guidance or cooperation or anything else. They would like to get on with their wolfy thing and would like you to get out of the way. So that wolves and animals that hunt in packs like that tend to have not big visible whites of the eyes as we do and as dogs do relative to other dogs, but they have contrasting fur around the eye so that you can see the direction of gaze. One of my speculations is that Neanderthals didn't have this. Maybe they didn't have whites to their eyes. It's such a rare trait in primates maybe they never evolved it.

A map depicting the range of Homo neanderthalensis. (Photo: Nilenbert; CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: This is the same trait that people playing American football -- defenders use. They look where the quarterback is looking to see where he is going to throw the ball.

SHIPMAN: That's exactly it.

CURWOOD: Of course, there's always a question. How does this begin? How did the modern human bring the wolf in and the domesticate the wolf or is it the other way around? Did the wolf domesticate the human?

SHIPMAN: Well, there certainly is a two way relationship going on. The way it probably happened - here's speculation again - is starting with pups. I'm guessing because it's such a normal human thing to do, somebody at some time picked up a lost puppy. It was little, it was cute, it was fuzzy. They took him home; they kept it around. If it got obnoxious they killed it and ate it. If it was a little less aggressive or a little more cooperative, maybe they continued to keep it around and later brought a second one in and so on. And so I think it has to have happened by accident. There was a very dominant theory that wolves might have actually domesticated themselves by hanging around village dumps, garbage dumps when there were first villages and towns. There are two points that mitigate against this idea. One is if they were really, around 40,000 years ago there weren't any permanent settlements. There weren't any garbage dumps so that's not going to work. The other side of it is that in fact wolves who are exposed to humans, who feed off garbage dumps now, who watch humans, those are the ones that are more likely to become aggressive and attack. So my money would be that it started almost accidentally with somebody taking home wolf puppies and over time you got a progressively more and more domesticated animal that understood people better, that communicated with people better and they kind of liked hanging around the campfire with people. So it's that ability to work with us, to work cooperatively, to add their skills to our skills, is a long and ancient story.

CURWOOD: Pat Shipman is author of "The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction". Thanks much for taking time with us today.

SHIPMAN: Thank you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth