February 25, 2011

Air Date: February 25, 2011

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Sometimes Frost

View the page for this story

Scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Snow and Ice Data Center have published a new study with surprising results. They found that the vast frozen tundra in the arctic region could soon defrost and release vast amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Host Bruce Gellerman talks with climate scientist Kevin Schaefer, the lead author on this study. (06:00)

Lessons from surging oil prices

View the page for this story

Global political turmoil is turning oil into an increasingly expensive addiction. Jim Woolsey, former director of the CIA, tells Living on Earth's Steve Curwood that the recent spike in prices at the pump could just be the beginning. (07:00)

Sustainable Science at EPA

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

The Environmental Protection Agency's top scientist says today;s environmental problems require a seismic shift in the way EPA works. Living on Earth's Jeff Young profiles Paul Anastas (uh NAS tus). The green chemistry pioneer wants to put the principles of sustainability at the center of EPA science. (06:00)

Smart Meter, Big Brother

View the page for this story

The goal of smart meter technology is to improve energy efficiency, cut greenhouse gases and save consumers money. But Kevin Doran, a Senior Research Professor at the University of Colorado, tells host Bruce Gellerman that these smart meters raise privacy concerns because they can potentially reveal personal details about customers' at-home behaviors. (06:30)

How Green are E-Books?

View the page for this story

Last year, sales of electronic readers skyrocketed in the U.S. As Raz Godelnik, CEO of Eco-Libris, tells host Bruce Gellerman, e-readers don't use any paper, but they still have a significant carbon footprint. For some readers, traditional books are the greener option. (06:00)

Where the Antelope Played

/ Jason AlbertView the page for this story

Recent natural gas discoveries in the eastern U.S. have changed the country's energy equation. But in the West a major gas rush has been underway for more than decade, and the conversion of landscape from rural to industrial continues there. Reporter Jason Albert tells this story of one corner of western Wyoming. (09:20)

Science Note/Crustaceans in the Reef

/ Sean FaulkView the page for this story

Researchers discover that crustaceans are able to detect and respond to the sounds of the coral reef. The study highlights how important ocean acoustics are to sea creatures, and how noise pollution from our ships could have a major impact on marine ecosystems. Sean Faulk reports. (01:30)

The Fearsome Nematodes of the Dry Valley

/ Glen ZorpetteView the page for this story

One of the driest places on Earth lies at the bottom of the world, the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica. A tiny worm is at the top predator in this desert, and scientists are subtly adjusting water and food levels to learn how food chains adapt to changing conditions. IEEE Spectrum's Glen Zorpette reports. (04:10)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Sounds of Weddell seal mothers and their pups in Antarctica.

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bruce Gellerman

GUESTS: Kevin Schaefer , James Woolsey, Paul Anastas, Kevin Doran, Raz Godelnik

REPORTERS: Steve Curwood, Jeff Young, Jason Albert, Sean Faulk, Glen Zorpette, Douglas Quinn

The Sometimes Frost

Large chunks of soil collapse as a result of permafrost thaw and erosion, as this image taken along the Sagavanirktok River on the North Slope of Alaska near Deadhorse shows. (Photo: Kevin Schaefer)

GELLERMAN: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville Mass, this is Living on Earth. I'm Bruce Gellerman. National security and energy security - a conversation with former CIA chief James Woolsey about the threat posed by our dependence on foreign oil. But first - the scales are tipping: global warming is converting vast carbon sinks into huge carbon emitters.

Two regions that store enormous amounts of climate changing gases are undergoing dramatic changes themselves. In recent years, devastating droughts in the Amazon have killed tens of millions of trees in the world's largest rainforest. As they rot, the dead trees will release 13 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. That's as much as China and the United States emit in a year. Now researchers warn even more CO2 could be released in the coming decades as global warming heats up the ground in the frozen arctic.

A thick layer of ground ice is clearly visible in this image of thawing permafrost taken just south of the Brooks Range in Alaska. (Photo: Tingjun Zhang)

Kevin Schaefer is a climate scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. Dr Schaefer, welcome to Living on Earth!

SCHAEFER: Thank you very much.

GELLERMAN: So, let's talk permafrost. What is it, and why should I care about what happens to it?

SCHAEFER: Permafrost is permanently frozen ground in the high-latitude tundra regions. You imagine on the surface of the ground you've got your vegetation, grasses and mosses. Underneath that you've got a layer of soil that thaws in the summer and freezes again in the winter. And underneath that is the permafrost, permanently frozen ground.

The permafrost starts only about a meter or so from the surface, but it can extend down thousands of feet. We should be concerned about this because the permafrost contains a large amount of frozen organic matter - organic matter that has been frozen since the last ice age, 30-10 thousand years ago.

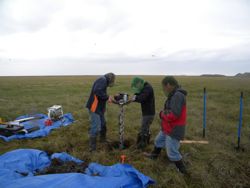

Scientists Tingjun Zhang and Kevin Schaefer explore a typical gully caused by rapid erosion as permafrost thaws on the North Slope of Alaska. Researchers call this landscape ith its irregular hummocks and bogs "thermokarst". (Photo: Lin Liu)

GELLERMAN: So, if I understand your research, what you're saying is that the permafrost is melting, essentially, it's thawing out - and that it's turning from a sink into a source, that is, it stored carbon dioxide and now it's going to be releasing it back into the atmosphere, these greenhouse gasses.

SCHAEFER: The best analogy we like to use is that you have broccoli in your freezer - as long as it stays in the freezer, it will stay stable for very long time, but if you take it out of the freezer, it will eventually thaw out and decay. And that's what we're talking about with the carbon, the organic matter that's currently frozen in the permafrost. This matter has remained frozen for tens of thousands of years. And as temperatures rise, as we put greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, it starts to thaw out. Eventually the thaw layer will reach the frozen carbon. Once it thaws out it will decay and the carbon will end up back into the atmosphere.

GELLERMAN: So, the earth is getting warmer because of greenhouse gasses - this causes the permafrost to thaw, which releases more greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, and that causes more warming, and on and on again.

Thawing permafrost leads to rapid erosion, and subsidence, often with small ponds like this, in a photo taken just south of the Brooks Range in Alaska. (Photo: Lin Liu)

SCHAEFER: Exactly. This is called the permafrost-carbon feedback. And, once the carbon is put back into the atmosphere, it will accelerate the warming due to the release of fossil fuel emissions.

GELLERMAN: So are we talking about a runaway climate change here?

SCHAEFER: No, we're not. We're not talking Venus. But we are talking a significant amplification. Now I can't tell you at this time exactly how many degrees additional warming we would see due to this - that's the next phase of our research - but I can tell you that it's a huge amount of carbon. And, we estimate that the arctic will change from a sink of carbon relative to the atmosphere, to a source, in about 20 years.

GELLERMAN: Well, you don't quantify how much carbon dioxide could be emitted?

SCHAEFER: Well, we do. We estimate by 2200, 190 giga-tons plus or minus 64 giga-tons of carbon put into the atmosphere. Now that's a lot of carbon, and to give a perspective, that's roughly equivalent to half of the total fossil fuel emissions since the dawn of the Industrial Age. Or to put it another way, it's equivalent to the emissions from all power plants in the United States for 80 years.

Expansion and contraction as the surface soil freezes and thaws each year form polygons in the permafrost, as seen here in a photo taken near Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. (Photo: Kevin Schaefer)

GELLERMAN: So, right now we're at, what, 390 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and scientists say that's above the safety level. They'd like to see it at 350. So, where would this put us in 90 years?

SCHAEFER: We estimate - maximum possible - about 80 ppm, roughly an additional 20 percent.

GELLERMAN: Instead of 390, we'd be up to'470?

SCHAEFER: Yes.

GELLERMAN: So, what happens to your numbers now?

SCHAEFER: Well, the next phase of the research is to do many more simulations to try to get a better handle on the uncertainty in our estimates. And also to work with other modeling teams to put this into a fully dynamic climate model, so that we could actually quantify how much additional warming or amplification we'd see due to the release of CO2 from permafrost.

Scientists drilling a permafrost core sample on the North Slope of Alaska near Deadhorse. Mosquitoes form a haze around the drilling team. (Photo: Kevin Schaefer)

GELLERMAN: Your figures have not been used in climate models before?

SCHAEFER: No. Ours is the first study to release how much and when carbon dioxide would be released from the permafrost. None of the other models in the inter-governmental panel on climate change include the permafrost-carbon feedback. I do know that many of the modeling teams are working right now to put permafrost-carbon into their models.

GELLERMAN: So what has to be done is we gotta make even greater cuts than are now being voluntarily agreed upon.

Large chunks of soil collapse as a result of permafrost thaw and erosion, as this image taken along the Sagavanirktok River on the North Slope of Alaska near Deadhorse shows. (Photo: Kevin Schaefer)

SCHAEFER: The release of carbon from permafrost is irreversible. Just like fossil fuels. Fossil fuels - once you drill the carbon, drill the oil and burn it, there's no way to put that oil back into the ground. In permafrost, once you thaw out the organic matter and it decays, there's no way to put that organic matter back into the permafrost.

So what it means is that we have to reduce our emissions even more in order to hit a target atmosphere CO2 concentration. The primary results of our paper is that permafrost can release a huge amount of carbon, and that we really have to account for that carbon when developing our global strategies to reduce fossil fuel emissions.

GELLERMAN: Well, Kevin Schaefer, thank you so very much, I really appreciate it.

SCHAEFER: Thank you.

GELLERMAN: Kevin Schaefer is a climate scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, CO. His study appears in the latest online edition of the journal Tellus.

Related links:

- Visit the National Snow and Ice Data Center's website

- Read the abstract of Dr. Schaefer's article

- Web Extra: Listen to Dr. David Lawrence from the National Center for Atmospheric Research respond to this article.

- Watch U.S. Energy Secretary Steven Chu talk about the warming feedback loop from melting permafrost.

- Read a Climate Progress article about this study.

Lessons from surging oil prices

James Woolsey.

GELLERMAN: Well, our reliance on fossil fuels not only has consequences for climate change but national security as well.

[PROTESTERS CHANTING]

GELLERMAN: Recent pro-democracy demonstrations have destabilized - even overthrown - autocratic governments in North Africa and the Middle East.

[GUN FIRE AND CHAOS]

GELLERMAN: The uncertainty and the sometimes brutal suppression of protesters in these troubled, oil-rich regions have sent the price of petroleum soaring. Since the wave of uprisings, oil has topped a hundred dollars a barrel, and prices at the pump have drivers and the economy hitting the brakes.

Jim Woolsey says for the U. S., the bad economic news could be just beginning. Woolsey directed the Central Intelligence Agency during the Clinton administration. He recently spoke with Living on Earth's Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: So, you have been a long-term advocate for dealing with the question of imported oil, for A) national security, and B) taking care of the environment. So, this has to be a moment that you have long anticipated.

WOOLSEY: Well, I think it's going to happen again and again and again, perhaps not with the revolutions throughout the Middle East, but for one reason or another, we will be in a situation in which we are paying huge amounts of money to other countries, many of which, as several Presidents have said, they don't like us very much - for our ability to transport anything, because transportation is dominated by petroleum products, about 95 percent, and OPEC controls close to 80 percent of the world's proven reserves of conventional petroleum.

Right now they're keeping the price high, even before this last round of revolutions, by pumping only about 40 percent of the world's oil, but holding on to close to 80 percent of its reserves.

CURWOOD: How large is the risk to our economy if there is an oil price shock out of the events now in the Middle East?

WOOLSEY: It's gigantic. At 100 dollar a barrel of oil, we are borrowing well over a billion dollars a day to import oil. Approaching two billion. And, suppose we get a 30-40 percent increase to where it was two years ago, 147 or so, 150, then we'll be borrowing close to three billion dollars a day to import oil.

CURWOOD: Wait a second. Your math is: if there's an oil price shock back to the peak level we saw last time, the U.S. is going to be borrowing three billion bucks a day from the world'that's a trillion dollars over the course of a year.

WOOLSEY: At a hundred dollar a barrel, we're borrowing close to a billion and a half - if you take it up to 150, say, it's two and a half billion a day. And it's one major reason why our debt is so high, and why the dollar is starting to be looked at askance as a reserve currency by some countries. It's stunning how' I mean, our oil debt is much bigger than our trade deficit with China. Everybody is worried about the trade deficit with China - well that's an important thing to worry about, we need to work on that. But the oil, the amount we borrow to import oil, is much bigger.

CURWOOD: So, what you're saying is that our balance of trade deficit, America's debt to the wider world, is going out for oil. At the same time, we're looking at cutting the federal deficit - there are moves there that would reduce federal spending on energy redevelopment, renewables, so on and so forth'in the present circumstances, how wise do you think that is?

WOOLSEY: Well, some of the things that we have done are really focused at electricity not oil, although people like to make speeches saying, 'Foreign oil is a problem, oil is a problem, therefore let's have nuclear power plants.' Well since only 1 to 2 percent of our electricity comes from burning oil these days, you can build all the nuclear power plants you want, but it has virtually nothing to do with getting off petroleum.

The same thing is true of wind farms - those may be two perfectly fine ways to produce electricity cleanly, but they don't really have anything to do with oil, and neither did cap-and-trade. Drill-baby-drill also is not the solution - that helps the balance of payments a bit, but with three percent of the world's oil reserves and 25 percent of the world's oil consumption, we're not going to be able to drill ourselves out of OPEC having effective control of the market.

CURWOOD: So, what's the solution?

WOOLSEY: What we have to do is break that monopoly oil has, and anything we can do to, not only use less of oil - that's not all that useful because the Saudis and others will just cut back production more in order to keep prices high - we've got to get off onto other fuels. And it's not that we're addicted to oil, as it has been said, it's that our cars are.

One thing is: look to Brazil - and require that all of our new vehicles be''flexible fuel, open standard' is the phrase. And what that means is that they can use any mixture of gasoline, or alcohols, and not just ethanol, but methanol, so-called 'wood-alcohol,' which can be made rather inexpensively these days out of natural gas. You can still produce it for two dollars and something a gallon with today's technology. What you can't do is use it in an ordinary car, because the fuel line is the wrong kind of plastic. And, it is a very small change, a hundred dollars or so in the manufacturing process, and what that would do is open up petroleum products, like gasoline, to competition.

CURWOOD: Now you've been making the national security pitch about getting off of oil for a long time - what kind of cultural resistance have you run into?

James Woolsey

WOOLSEY: Normally, what happens is that people say, 'Oh yeah, I know it's a problem, but we can't really spend the money to do it just yet.' It's always, not refutation, but delay. It's one reason why I've gotten particularly interested in Boyden Gray's point, published in a very detailed article a couple of years ago, that what the oil companies use to enhance octane, once we got the lead out back in the 70s, is so-called aromatics - benzene, toluene, xylene - it's that sweet smell that you smell when you're pumping gasoline. Those are highly carcinogenic.

And, Boyden's calculations indicate that well over a hundred billion dollars a year in added health care costs and shortened lives, come from us using that to enhance octane. Well, you could use alcohols instead. You can use methanol made from natural gas and it's not carcinogenic.

So I keep trying with the national security issues, and climate change issues, and pollution issues and now health care issues - whatever will work. I look on oil, sort of, as I guess maybe the G-Men back in the 20's and 30's looked at Al Capone. He's done a lot of things wrong, and if you can't get him for murder, get him for tax evasion. But - whatever works.

CURWOOD: James Woolsey is the former director of the Central Intelligence Agency and now a senior fellow at the Jackson Institute at Yale University. Thank you so much, sir.

WOOLSEY: Good to be with you.

GELLERMAN: There's more of Steve's interview with Jim Woolsey - and more about the melting arctic at our website, L-O-E dot ORG.

Related links:

- Click her for Boyden Gray's paper on the health costs of petroleum.

- More of Woolsey on independence from oil.

- Listen to an extended interview with Jim Woolsey.

[MUSIC: Jeff Beck 'Cause We Ended As Lovers' from Blow By Blow (Sony Music 1975).]

GELELRMAN: Just ahead - smart meters are coming and you may find them too smart by half. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

[CUT AWAY MUSIC: Ernest Ranglin: 'Black Disciples' from Below The Bassline (Island Records 1995).]

Sustainable Science at EPA

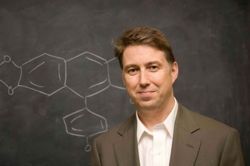

Dr. Paul Anastas pioneered the field of green chemistry, which he calls 'the molecular basis of sustainability. (Yale University Green Chemistry Center)

GELLERMAN: It's Living on Earth, I'm Bruce Gellerman. The Environmental Protection Agency recently turned 40, and like a lot of 40 year olds, the agency is taking a midlife look in the mirror - metaphorically speaking, anyway - and planning some big changes.

The EPA is undertaking what some call a 'seismic shift' in the way it works: making "sustainability" its central goal. To do that, the agency is counting on Paul Anastas. The EPA's top scientist has a long track record of putting sustainability to work. Living on Earth's Jeff Young has this profile.

YOUNG: The Environmental Protection Agency started in 1970, a time when smokestacks belched pollution and rivers occasionally caught fire. The problems were big and plain to see. EPA assistant administrator Paul Anastas says today's problems are big, but a bit murkier.

ANASTAS: When we start looking at complex problems like climate change, subtle problems such as endocrine disrupting chemicals - they are more complex, they are more subtle, and they're going to need a new approach, a new thinking. There's a great quote from Albert Einstein - he said, 'problems can't be solved at the same level of awareness that created them.'

And so when we look at our current state of the environment, one of the things that we're trying to do is say, 'What's our new level of awareness?' That's what we're trying to do at the EPA today.

YOUNG: Anastas leads EPA's office of research and development. He's also the agency's science advisor - in effect its top scientist. EPA's science has long rested on narrowly focused specialists deciding how much harm people and nature can tolerate. Anastas wants his scientists to think more broadly about systems and sustainability.

ANASTAS: Systems thinking means that we're going to be asking questions about how not only can we make things less bad - how do we make things better, more sustainable, more healthful. Sustainability is our true north.

YOUNG: So how might this approach that you're talking about make you better able to address a challenge like climate change?

ANASTAS: Well climate change is a key issue. Climate is inextricably linked to energy, energy inextricably linked to water, water to agriculture, agriculture to health, and we could go on and on. If we start saying that the entirety of our approach to sustainability is simply to reduce our carbon footprint or to look at any one aspect, then we will not be getting the power and the potential of the synergies of looking from a systems approach.

Dr. Paul Anastas pioneered the field of green chemistry, which he calls 'the molecular basis of sustainability.' (Yale University Green Chemistry Center)

YOUNG: Now, forgive me if this is an unfair stereotype, but it's my impression that the agency generally goes about its business by - well, you have an expert who does water, and you have experts who do air. How do you get those different experts to all think horizontally as well as up and down?

ANASTAS: Well, you ask precisely the right question. It's not just bringing together a couple scientists. It's bringing together physical scientists, life scientists, economists, communication specialists, social and behavioral scientists - the broadest spectrum of perspectives. So, we need to understand the underlying nature of our materials and our energy.

Are they depleting, are they degrading of our natural ecosystems, are they benign to humans and the environment or are they inherently hazardous, are they resilient, or are they vulnerable? These kinds of questions are not easy questions. They just happen to be the questions that we must ask and answer if we're going to address these challenges systemically.

YOUNG: Anastas says the EPA is beginning to work this way in its assessment of toxic chemicals. That's the area where Anastas is best known. Terry Collins directs the Institute for Green Science in the Department of Chemistry at Carnegie Mellon University. He first met Anastas in the early 90's during his first stint at EPA.

COLLINS: He was a young chief of toxics at EPA, in his late 20's I think, and he'd been looking at the way the EPA functioned, which is really saying, 'No, you can't do that' or trying to say, 'No, you can't do that.' And he felt that the organization would be so much better off if it was instead encouraging industry to develop products and processes that weren't toxic in the first place. And he coined the name 'green chemistry,' and I really regard him as the father of green chemistry.

YOUNG: Anastas wrote many of green chemistry's most influential books and won the prestigious Heinz award for his vision of chemistry that eliminates toxic risks. He was director of Yale's Center for Green Chemistry and Green Engineering when President Obama tapped him for a return to service at EPA. A talk with Anastas makes clear that the sustainability effort at EPA owes a great deal to green chemistry.

ANASTAS: Green chemistry is the molecular basis of sustainability - recognizing that all we have in this world is energy and matter, energy and material, and how you redesign the material basis of our society and our economy so that they are sustainable and benign.

YOUNG: This does not sound like a tinkering-around-the-edges kind of change. You're talking about real, kind of, fundamental change about the way you guys go about business here.

ANASTAS: Yeah, this is a seismic shift. While I know that the public often doesn't think about the words 'EPA' and 'innovation' in the same sentence, this is not your grandfather's EPA.

YOUNG: Anastas knows the change he's after won't come quickly or easily. EPA has asked the National Academy of Sciences for help. Nearly thirty years ago the Academy helped shape EPA science with a publication called the Red Book.

It was a how-to guide on putting the principles of risk management to work at EPA. Now the Academy is considering a similar guide on how to incorporate the principles of sustainability. The academy's report, expected this summer, is already being called the 'Green Book.' For Living on Earth, I'm Jeff Young.

Related links:

- National Academy of Sciences panel on sustainability at EPA

- EPA bio page for Dr. Paul Anastas

- Yale's Green Chemistry Center

[MUSIC: Captain Beefheart 'When I See Mommy I Fell Like A Mummy' from Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) (Warner Brothers 1978).]

Smart Meter, Big Brother

A smart meter. (Wikipedia Creative Commons)

GELLERMAN: Nearly 9 percent of the electric meters in the U.S. are smart - and more are on the way. These high I.Q. devices are designed to improve energy efficiency, cut greenhouse gases, and save you money.

All good things, but smart meters may be a lot smarter than you think - and know a lot more about you than you might want. Kevin Doran monitors smart meters. He's a research professor at the Renewable and Sustainable Energy Institute at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Welcome to Living on Earth!

DORAN: Thank you!

GELLERMAN: So what makes a smart meter so smart?

DORAN: The idea behind a smart meter is that it communicates information to the utility, and in theory, the utility can also use that pathway, if you will, to send information back to the consumer, in terms of price signals, or in terms of switching off appliances when they're on but not being used and could be saving electricity. So, you think of it like this: you've got your traditional electricity system - transition, distribution - we're all familiar with that. The smartness comes into play when you add information on top of that.

Researcher Kevin Doran. (Photo: Kevin Doran)

GELLERMAN: Well, what can a utility know about me from a smart meter that they couldn't tell from a dumb meter?

DORAN: Well, think of a dumb meter - it just says to the utility, 'This is how much power you're using.' Now think about a smart meter that is hooked up to all of the appliances in your homes. When you're in a certain part of your house and you're turning on lights, the smart meter is knowing that. So all of these things that were kind of hidden to the utility, or to other interested parties, become capable of being discerned because of the information that's being sent through that meter.

GELLERMAN: So it can tell whether I'm toasting a bagel or getting a back massage?

DORAN: Well, no. But certain appliances definitely have certain energy signatures. So it could tell if you were using a microwave, which has a certain kind of signature. It could tell if you're using an oven, which has another kind of signature.

GELLERMAN: So how is this data from a smart grid any different than, you know, smartphones, or the data that comes from my using an E-Z Pass on the road, or Facebook?

DORAN: You know, it's becoming an increasingly transparent society that we live in. One of the concerns, especially with smart grid, is that so much of this is happening inside the home. And we've traditionally viewed the four walls of the home as a sacrosanct place of privacy. What smart grid does is it takes those four walls and it makes them essentially transparent.

And all of the intimate personal details that we assumed are our own, because they happen within those four walls, are now being communicated to utilities. And they're using this information to manage their load better - to make sure that customers are not using power at, let's say, peak power times, but using it at different times in the day so that they can use their system more efficiently. That very beneficial use aside though, there are all sorts of other kinds of information that come through the smart signal that could be capable of being used nefariously.

GELLERMAN: But it gets a lot more specific - you write that it can tell how often you arrive home around bar time, are you a restless sleeper, do you get up frequently throughout the night'they can tell all this from the smart meter's information?

DORAN: Yes and no. The information is just the information about the power usage that's happening in your house, and then potentially, about the kinds of appliances and when they turn on and when they turn off. That said, there's a whole lot of extrapolation that can be done on that data to figure this kind of information out.

So, to give you the example of: do you come home from'around the time when the bars close? So, you pull into your house and you start turning on all your lights. And then it becomes clear that somebody is now home, and let's say that it's around two AM, which is when the bars are closing. An insurance company looking at this information could see a pattern that shows that this person is routinely coming home at this period of time, and then make a correlation or an assumption that says, 'Ah, perhaps they're out there drinking, and we should have higher premiums for them.'

So, it isn't just the data. The data is one thing - but it's also the kind of sophisticated correlations and comparisons and data parsing that can be done on that data to figure out all sorts of things about a person's life.

GELLERMAN: Data mining.

DORAN: Data mining, essentially, yes. And it becomes even more concerning - I think, from a privacy perspective - when you realize it's not just about the smart grid data anymore. You know, our lives are increasingly digitized and placed online for other people to look at.

So it's about the movie preferences that you make at Netflix, or the blogs that you're participating in - and the reason I bring this up is because all of these data sets are floating out there. Now if somebody, for nefarious purposes, wanted to take your smart grid data and start hooking it up with other kinds of data about you online - financial data, for instance - you can fairly quickly see how easy it would be for a sophisticated user to reconstruct virtually everything about you. Your digital doppelganger would become clear.

A smart meter. (Wikipedia Creative Commons)

GELLERMAN: So the real question is: who has access to the smart meter information?

DORAN: Yeah, that is a critical question - and this is up for grabs. This is a battleground between utility companies, third party service providers that would like to be able to use this data to help customers manage their information, and people like marketers and advertisers who would like access to that information, and then consumer privacy advocates and consumers themselves.

And as policy makers figure out how to approach this entire new terrain, they need to be cognizant of the fact that there are serious privacy concerns out there, and much of the legislation and statutes that deal with privacy have no idea what to do when it comes to the smart grid because this is so new.

GELLERMAN: Professor, do you have a smart meter at home?

DORAN: I do not. I live in a town outside of Boulder, which is the subject of an experiment by the local utility here - it's called the Smart Grid Boulder City Experiment. So many of the people in Boulder do have smart meters on their homes.

GELLERMAN: And when a smart meter comes knocking on your door, what are you going to do?

DORAN: I'm gonna say yes. Because I think that we can do this. I think that we can do it in a way that makes sense for environmental, energy efficiency purposes, and that we can also figure out a way to make sure that this data is used appropriately. The critical questions upfront are going to be: who owns the data, and what kind of protections are placed on that data? And, although I'm sure it will not be a pain-free experience as we figure these answers out, I think at the end of the day, we'll be happy.

GELLERMAN: Well, Professor Doran, thank you very much, really appreciate it, learned a lot.

DORAN: My pleasure.

GELLERMAN: Kevin Doran is Assistant Research Professor at the Renewable and Sustainable Energy Institute at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Related link:

Visit the University of Colorado at Boulder's Renewable and Sustainable Energy Institute

[MUSIC: Jason Moran 'Planet Rock' from Modernistic (Blue Note Records 2002).]

How Green are E-Books?

Eco-Libris plants trees throughout Central America and Africa. One of their planting partners in Guatemala, AIR, has already planted tens of thousands of trees.

GELLERMAN: The ebook is writing a new chapter in the way we read. Last year, Amazon - the online retailer - sold 3 times more electronic books than hardbacks'and for the first time, more ebooks than paperbacks. You might think the revolution in reading - replacing paper with electronic digits - saves on greenhouse gases, but Raz Godelnik has measured the carbon footprint of ebooks, and they don't stack up well against the old-fashioned kind.

Raz Godelnik is the co-founder and CEO of Eco-Libris - it's a company working to green up the book industry in the digital age. He joins us by Skype - and Raz Godelnik, welcome to Living on Earth.

GODELNIK: Thank you!

GELLERMAN: I was amazed to read in an article you wrote that the average paperback is a pretty hefty tome - it has a greenhouse gas footprint of, what, four kilos? That's ten pounds! How is that possible that it should be ten pounds worth of carbon from one little book?

Raz Godelnik is the CEO and co-founder of Eco-Libris (Courtesy Raz Godelnik)

GODELNIK: Well, it's true that it looks like a little book, but the whole manufacturing process is a process that includes cutting of trees, and then using a lot of energy in the manufacturing process in paper mills, and eventually transporting the books to warehouses and then to bookstores. It's a long process, but most of the carbon footprint comes from the beginning of the process - more than 80 percent of the whole carbon footprint of the book.

GELLERMAN: Well let's compare that, say, to an Apple iPad, which only weighs in at about a pound and a half. How big is the Apple iPad's carbon footprint?

GODELNIK: Well according to Apple, the iPad has a carbon footprint that is equal to the footprint of about 32 paper books.

GELLERMAN: One Apple iPad equals the carbon footprint of 32 paperbacks?

GODELNIK: That's true.

GELLERMAN: How about other eReaders? Like, the Kindle?

GODELNIK: So, when it comes to the Kindle, which is the main eReader in the market, the problem is that we don't have any data because Amazon doesn't reveal anything. Not only that Amazon doesn't volunteer to do so, they were asked many times to reveal the carbon footprint or other information related to the footprint of the Kindle, and so far, we just don't have anything from them.

Eco-Libris plants trees throughout Central America and Africa. One of their planting partners in Guatemala, AIR, has already planted tens of thousands of trees.

If we want to make the Kindle more eco-friendly, first we have to know, you know, what's the starting point.

GELLERMAN: So, you want the book industry to turn over a new leaf?

GODELNIK: (Laughs.) Definitely! It's true. When you look at eReaders, most readers assume instinctively that they're greener and better from an environmental point of view because, you know, you save paper. But again, the thing is that we see a new product with some new issues. So, usually when I'm asked if e-reading is greener than traditional reading of paper books, my reply is that it depends.

It depends on the profile of the reader. If you're an avid reader and you read many books, probably the eReader is a greener option for you. But, if you read only a couple of books a year, it might be that paper books - that traditional books are still a better option when it comes to the environmental impact of your reading.

So, it definitely depends, and of course, it also depends on how much time are you going to keep the eReader that you're having or that you're planning to buy. Is it only for one year until the next version will be out, or is it for five years? So, there's definitely no one answer for everyone, but it's an individual answer for each and every reader.

GELLERMAN: One of the things that your company Eco-Libris is trying to do is having people contribute a buck to buy a tree - each time they read a book.

GODELNIK: Oh, yes. One of the things we work on is to make reading more sustainable. And part of our operations is a tree-planting program that we have, where we encourage both readers and publishers to plant trees for the books that they either read or publish, and we have these trees planted in Central America and in Africa - places that suffer from deforestation - where these trees benefit both the environment and the local community.

GELLERMAN: How many trees have you bought so far?

GODELNIK: Well, so far we have planted with our planting partners about 180,000 trees, and we look forward to planting many more.

GELLERMAN: Raz Godenik is CEO of Eco-Libris. Read all about it on our webpage, L-O-E dot O-R-G.

Related links:

- See if e-readers or traditional books are the greenest option for you.

- Plant a tree for every book you read.

[MUSIC: Ernest Ranglin 'Congo Man' from Below The Baseline (Island records 1995).]

GELLERMAN: Just ahead - big changes for big sky country as gas wells put pressure on the environment - stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[CUT-AWAY MUSIC: Joshua Redman/Various Artists: 'You've Got A Friend In Me' from everybody Wants To be A Cat (Disney Records 2011).]

ANNOUNCER: Support for the environmental health desk at Living on Earth comes from the Cedar Tree Foundation. Support also comes from the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund for coverage of population and the environment. And, from Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is Living on Earth on PRI - Public Radio International.

Where the Antelope Played

Drill rig and well pad on the Anticline. At night the rigs sparkle like Christmas trees.

GELLERMAN: It's Living on Earth, I'm Bruce Gellerman. Sublette County, Wyoming is the size of Connecticut - but the population: just six thousand residents. Pinedale is the county seat and home to the Museum of the Mountain Man, which chronicles those who explored this vast, rural region in the 19th century. In the 21st century, it's the search for natural gas that draws attention to this part of big sky country.

The Jonah Field and the Pinedale Anticline are two of the largest gas fields in the nation. The deer and the antelope literally play atop the fields but the drilling is changing the landscape where they live'perhaps permanently. Jason Albert reports.

Pinedale welcome sign says it all.

[FEET CRUNCHING IN SNOW TRANSITION FADE INTO WIND]

ALBERT: The mountain and sage lands in this part of western Wyoming are sometimes called the North American Serengeti.

BOTUR: There's a lot of country out there, and a lot of pockets for the antelope, the mule deer, sage grouse. ALBERT: That's Freddy Botur, a ranch owner outside of Pinedale. When winter snows pummel the big hills, herds of pronghorn antelope and deer come down to a broad table, or mesa, here. Winds brush aside the snow, exposing just enough grass and sage to sustain this big game.

BOTUR: It doesn't have trees, it doesn't have lakes, it doesn't look anything spectacular like a national park. But this is that kind of in-between land between the mountains and the desert and that's really important.

ALBERT: Really important for the animals here because they burn crucial fat reserves once the Arctic air moves in. Rollin Sparrowe is a wildlife biologist with over four decades of experience. We meet in his cabin to escape the zero-degree cold.

SPARROWE: Winter concentration areas for mule deer in the Northern Rockies are the key to their future survival. The fate of the herd for that year is going to be determined by the condition of those animals coming off that winter range and heading back up to breed again.

ALBERT: But Sparrowe says he fears for this rhythm of big game that local hunters have tracked for generations. A decade ago, energy companies arrived. They call the mesa the 'Anticline.' It's rich with natural gas.

Some portions of the Anticline are off limits to energy operators during winter range closures. But operators may still drill and conduct maintenance year-round on many wildlife wintering grounds.

SPARROWE: In Sublette County about three years ago, there was 4 billion dollars of revenue from all the oil and gas and a lot of it was coming off the Anticline. And it was pretty clear that that was the big ticket to everybody.

ALBERT: Since then, this place has changed to its core.

[SOUNDS OF MORNING TRAFFIC'DIESEL ENGINES]

ALBERT: On Pinedale's main drag, The Corral Bar and Grill and Stockman's Restaurant tell of the town's ranching roots. Weather, rain, and cattle futures used to be what mattered here - now, it's global gas prices. There's a rush hour here now, as heavy-duty 4x4's haul rough necks to the field.

A frigid Pinedale main street speaks to the town's ranching roots.

[SOUND OF CAR DOOR CLOSING, CAR ON ROAD]

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I'm Kevin Williams - I'm the district manager for QEP in Pinedale.

ALBERT: Williams hops into the company rig and heads to the gas patch. Beyond his windshield, mountains loom over vast sagebrush.

WILLIAMS: Well, the Anticline is basically an underground mountain. It was created when the uplift of the Wind Rivers and the Wyoming Range created a buckle in the crust that allowed for the gas to be trapped and not escape to surface and into the atmosphere.

Sunset on the Wind River Range. A wild backdrop to the Anticline and its gas-drilling industrial din.

ALBERT: Williams says the geology reveals sandbars deposited by ancient rivers.

WILLIAMS: A lot of people liken it to a bowl of potato chips. You stick a straw in it, you only hit so many potato chips. Thus the need to drill more wells to be able to recover all the resource.

ALBERT: What he's alluding to becomes clear in a moment.

WILLIAMS: We're turning on Paradise Road.

[SOUND OF BLINKER, INDUSTRIALS SOUNDS]

Drill rig along Paradise Road.

ALBERT: The sage lands suddenly recede. Drilling rigs tower into a frigid bright blue sky. Four Wal-Mart-sized parking lots swarm with activity.

WILLIAMS: So you can see, you know about a mile and a half up is that rig, kind of same thing over there.

[INDUSTRIAL NOISE]

ALBERT: On squares of flattened earth known as wellpads, work crews drill while others prepare to 'frack' - the controversial practice used to 'fracture' bedrock to enhance gas extraction.

WILLIAMS: Red Halliburton trucks. You can see how they have piping coming off the back. So there's a pump - they're all manifolded together, getting ready to pump a frack job.

ALBERT: From here, it's hard to fathom the Anticline as anything but an energy patch. Yet Callie McKee from Ultra Petroleum has a trained eye.

MCKEE: You see the antelope out there.

Drill rig and well pad on the Anticline. At night the rigs sparkle like Christmas trees.

ALBERT: Energy operators have made concessions to wildlife here. In fact, many people point to this area as a model for progressive practices. One is a liquid gathering system. Wells here produce huge quantities of a gas by-product that liquefies at the earth's surface. This system captures the fluid in a lengthy series of enclosed pipes. Before, all this liquid had to be trucked to tanks - hundreds of them.

WILLIAMS: Between the three operators, we'll eliminate over 165,000 truck trips a year. So I mean that's a lot of trucks. And so you can imagine this is happening 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

ALBERT: Thanks to gas, the coffers of Sublette County are fat. School classrooms are stocked with supplies. There's a gleaming aquatic center. Pinedale also boasts a new 'green' library, where solar panels capture sunlight and where I met Laurie Latta.

LATTA: To me, as a longtime Sublette County person who has watched communities die, when you see those young people coming in that are educated and have new ideas and they have good jobs and they can contribute to this community. I mean there are a lot of things about the oil and gas industry that you can say, 'Ooh that's bad,' but there are a lot of things that are good about it too.

ALBERT: For folks in Pinedale, like Latta, the radical landscape conversion is bittersweet.

LATTA: You know, my husband and my sons are hunters. They used to go south of Pinedale onto what is now the Anticline and hunt antelope, and it was a big family male-bonding experience, and they can't do that anymore. Because of course there's pipelines and roads and everything - it's not the way that it was before. My younger son - it particularly bothers him that he can't do what he loved to do as a child. Um, life is a trade off.

[NOISE FROM GAS WELLS]

ALBERT: Once the wells are drilled and the rigs move on, the long-term tradeoffs are stark. Wellpads are bare. Federal and industry officials say sage-stripped hills will be replanted. Habitat will be returned.

But sagebrush ecosystems take decades to revitalize. Some here say, off the record, this area is a sacrifice zone for natural gas, and may never come back. In October, a report showed the population of mule deer down by more than half in the past decade.

ALBERT: But some places in the region, like that ranch belonging to Freddy Botur, who we heard from earlier, are being set aside.

[SNOW CRUNCHING, FENCE OPENING AND CLOSING, BARN DOOR CLOSING]

Freddie Botur of the Cottonwood Ranches outside Pinedale.

ALBERT: Botur once feared his Cottonwood Ranches would be drilled. He does not own the mineral rights here.

BOTUR: My first year on the ranch, I was negotiating 3-D seismics, 2-D seismics, pipelines - I spent more time with lawyers than I did with anybody else. That was my first awareness that when you don't own mineral rights, you really are subservient to oil and gas companies.

ALBERT: But when the test drilling was done, it turned out there was no major gas on the ranch.

BOTUR: And my argument has always been, well there's very little gas here and so there's low energy potential and high wildlife potential.

[CAR NOISES]

Small town saloon with big ambition.

ALBERT: So Botur protected the ranch with a conservation easement, funded by energy companies. From a high place on the property, he looks down on crescent shaped Muddy Creek and miles of sage uplands.

[CAR PARKING, SNOW CRUNCHING, WIND]

BOTUR: So all this that you're looking at here - all these fingers and benches and draws - we're looking at forever.

ALBERT: In the new west, forever is not limitless. Botur squints and looks to the horizon.

BOTUR: To the east-southeast here, you can see a typical mesa. That's actually the Anticline. And if you were to come out here at night you can definitely see the lights. I mean this used to be one of the darkest places most people have ever been. And now it looks like Denver is on the horizon.

[SOUND FROM GAS WELLS]

ALBERT: Up on the Anticline, a herd of forty pronghorn settle in deep, drifted snow. The reality is this stretch of western Wyoming offers highly concentrated gas under critical winter habitat. The antelope huddle close together. Not fifty yards away, gas wells gurgle and hiss. With a close listen, you can hear the breath of dinosaurs. For Living On Earth in Pinedale, Wyoming, this is Jason Albert.

Related links:

- Wyoming Conservation Group

- Pinedale Anticline Producers Association

- BLM Pinedale Anticline Working Group

- Western Oil & Gas Monitoring Group

[MUSIC: Led Zepplin 'The Rain Song' from Houses Of The Holy (Atlantic Records 1973)]

Science Note/Crustaceans in the Reef

A Coral Crab. (Photo: Jeffrey N. Jeffords - Divegallery)

GELLERMAN: Coming up: a visit to one of the world's most extreme deserts - but first this note on emerging science from Sean Faulk.

[SOUNDS OF A CORAL REEF]

FAULK: A coral reef is a noisy place, filled with sounds of clicking fish and snapping shrimp. That's important for reef-dwelling fish who head towards the noise to find their way back home.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

A Coral Crab. (Photo: Jeffrey N. Jeffords - Divegallery)

FAULK: Now, researchers at Bristol University in the UK think reef noise is also important for crustaceans like shrimp, crabs, and lobsters - creatures previously thought to be deaf. Marine biologists collected almost 700,000 crustaceans from the Great Barrier Reef and put them into a large pool. They set up an underwater sound system that streamed a recording of a coral reef and what they saw surprised them.

Crustaceans like crabs and lobsters that live in reefs scuttled towards the noise, while others, those that eat plankton and have predators in reefs, scurried away. The scientists say their study highlights how important ocean acoustics are to sea creatures and how noise pollution from our ships could disrupt marine ecosystems.

A recent study showed that in the last 50 years, man-made noise in the ocean has increased a hundredfold. If we continue at that rate, our industrial noises may drown out the chirps and snaps that make up the chorus of the coral reef.

[SOUND OF THE CORAL REEF]

FAULK: That's this week's Note on Emerging Science, I'm Sean Faulk.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

The Fearsome Nematodes of the Dry Valley

Scientists look across the Mc Murdo Dry Valleys. (Peter Rejcek)

GELLERMAN: The McMurdo Dry Valleys are more like Mars than any place on Earth - and you have to go to the ends of the Earth to reach them. That's what Glen Zorpette did for IEEE Spectrum. Here's his report from the series: 'Antarctica: Life on the Ice.'

ZORPETTE: The Dry Valleys are among the most arid places on Earth. There's very little snow, and not a lot of ice except for some scattered glaciers. And yet inside the Taylor Valley where I was standing'

[SOUND OF WATER TRICKLING]

A cluster of laboratory huts is perched near Lake Hoare in the Taylor Valley, one of the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica. Scientists at the camp are studying the life cycle of the nematodes in the valley. The nematodes, a kind of roundworm, are the most advanced form of life indigenous to the area. (Photo: Glenn Zorpette)

LEVY: And when I came down into Taylor for the first time and heard that water trickling, it almost brought a tear to my eye.

ZORPETTE: Joseph Levy is a postdoctoral fellow with Portland State University and the McMurdo Long Term Ecological Research group, also known as the LTER.

LEVY: After two months of not hearing any liquid water except for what we have in the pot, and this is just - I love it.

ZORPETTE: Levy knew exactly where that noise of trickling water was coming from.

LEVY: That's the sound of some old ice. That's water deposited 4000 years ago.

[SOUND OF WATER TRICKLING]

ZORPETTE: Up in the accumulation zone of one of the glaciers, apparently.

Researcher Joseph Levy explains the unusual features of the Taylor Valley, in Antarctica, to CBS reporters Edward Forgotson and Josh Landis (in gray jacket). Taylor Valley is one of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, whose unique ecology attracts researchers from all over the world. The valleys are the largest ice-free area in Antarctica. Their cold climate and relative lack of humidity and living organisms makes the valleys the closest terrestrial analogue to Mars. (Photo: Glenn Zorpette)

LEVY: And right now, when the sun shines during the peak summer, it melts, flows down over the frozen ground surface and out into the lakes. So that's why I'm really interested: the ground - it's this big unexplored source for water, for chemistry, for all the things that the LTER is interested in.

ZORPETTE: These little trickles of water sluicing their way through the Dry Valleys can mean the difference between dormancy and animation to some rather well-adapted creatures.

LEVY: The dominant predator here in the Dry Valleys is the fearsome nematode. It's a microscopic worm that eats both algae and also other microbes.

ZORPETTE: Are there nematodes unique to this area? Are there specific adaptations that you've seen with them?

The rugged terrain of the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica offers some of the most breathtaking scenery on Earth. They valleys are the largest ice-free area on the continent of Antarctica, which is 99.6 percent covered by ice. (Photo: Glenn Zorpette)

LEVY: The nematodes - most of them are endemic, so they're from here and unique to here. They adapt to the subfreezing temperatures in the winter by drying themselves out, and as soon as the first trickle of water comes from either melting snow in the spring or a trickle of water off a glacier, or in my interest, the melting of permafrost and the wicking up of water, they snap into activity and start eating, respirating, multiplying, and living their lives in the summer.

ZORPETTE: Nematodes belong to a simple food web to which Levy and his team are making small experimental tweaks. They add some extra water here, some extra food there, and observe how food webs respond to a changing environment.

LEVY: And given that we're part of a larger food web, even just understanding how the nematodes adapt is telling us a little bit about how we adapt as a species.

The mummified bodies of long-dead leopard seals are scattered around the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica. The seals occasionally haul their heavy bodies tens of miles and over rugged mountains into the valleys, and then die there of starvation. With little or no bacteria or humidity in the valleys, the mummified bodies can last for centuries. No one knows why the seals wander into the valleys. (Photo: Glenn Zorpette)

ZORPETTE: Very few critters other than nematodes can live in the Dry Valleys. Take seals, for example. Rae Spain is a Raytheon employee who assists the scientists.

SPAIN: We have a lot of mummified seals up and down the valley. We're not really sure why they come up here. For some reason, they tend to go further and further up valley, which you're gaining altitude, and you're going over big lumpy rocks. It can't be easy travel, because they travel much better in water. And then they die, of course, because they're not going back to sea.

Rae Spain, who assists researchers in Antarctica, walks near a glacier in the Taylor Valley. The valley is part of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, which occupy 4,800 square kilometers, and are the largest ice-free area in Antarctica. The unique ecology of the valleys, which are extremely arid and largely free of bacteria are strictly protected by a United Nations charter. (Photo: Glenn Zorpette)

ZORPETTE: The seals will wander as far as ten or twelve miles away from the sea, hauling their blubbery bodies over rugged mountains and hills.

SPAIN: Long way for a seal. With little tiny flippers for feet. And then they don't - there's no bacteria here to break them down. So they just desiccate. They just dry out and then become a bag of bones with beef jerky around them.

ZORPETTE: Goes to show just how hostile the Dry Valleys can be. Still, Joseph Levy finds the Antarctic, and the Dry Valleys in particular, an endlessly rewarding habitat to explore.

LEVY: On those few occasions when the wind dies, and you're ten or fifteen miles from camp, you're the only soul in the valley, and it's absolutely breathtaking. The opportunity, though, to really study this place - to understand it, to get an appreciation not just of its surface beauty but how it's functioning and how it's changing with time - is really the great opportunity. It is a life-changing experience, and it's a very addictive place to do work. There's a lot of data here, and a lot of information, and it's critical because - as you can hear - it's melting out every day.

[SOUND OF WATER TRICKLING]

ZORPETTE: For Living on Earth, I'm Glenn Zorpette in the Taylor Valley in Antarctica.

GELLERMAN: Glenn's story comes to us from the IEEE Spectrum documentary 'Antarctica: Life on the Ice.'

Related links:

-

- McMurdo Dry Valleys Long Term Ecological Researh (LTER)

-

[MUSIC: Nguyen Le 'Snow On A Flower' from Walking On The Tigers Tail (ACT Music 2005).]

GELLERMAN: From the dry valleys of Antarctica to its wet seashore, we leave you this week at the bottom of the world with Weddell seals.

[CALLS OF THE WEDDELL SEALS]

GELLERMAN: Weddell seals live further south than any other mammal, and are found in the chilly waters all round Antarctica. They can grow to be about nine feet long and weigh as much as thirteen hundred pounds. The seals live on fixed ice that's attached to the coast, but in the winter, they stay in the water to dodge blizzards. Douglas Quin recorded the calls of these mother seals and their pups for the Wild Sanctuary CD, Antarctica.

[SEAL CALLS: Douglas Quin 'Weddell Seals (Mother and Pups) from Antarctica (Wild Sanctuary 2002).]

GELLERMAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, Mitra Taj, and Jeff Young, with help from Sarah Calkins, and Sammy Sousa. Our interns are Sean Faulk and Wynn Tucker. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org. And while you're online, check out our sister program, Planet Harmony. Planet Harmony welcomes all and pays special attention to stories affecting communities of color. Log on and join the discussion at my planet harmony dot com. And don't forget to check out the LOE facebook page, it's PRI's Living on Earth. Steve Curwood is our executive producer. I'm Bruce Gellerman. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science

Foundation supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield farm, organic

yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth

hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from

you, our listeners, the Ford Foundation, the Town Creek Foundation, the Oak

Foundation - supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, dedicated to the idea that all people deserve a chance to live a healthy, productive life. Information at gates foundation dot org. And Pax

World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors

into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at pax world dot com.

Pax world, for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI ' Public Radio International

[All Living On Earth music themes composed by Allison Lirish Dean (2001)]

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth