Chasing Springtails

Air Date: Week of June 28, 2013

(United States Department of Agriculture)

The tiny creatures called springtails used to be described as insects, but were reclassified as a different order altogether called collembola a dozen years ago. There are 8000 species of springtails, and they're ubiquitous in caves, mountaintops, the tropics and the arctic. But Ari Daniel Shapiro reports that some species of collembola are facing extinction due to climate change and habitat loss.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Like them or not, our whole web of life depends, ultimately, on the broad and amazing variety of organisms on this planet, including many science has yet to identify. And among those unrecorded millions of life forms are some that inhabit a peculiar branch of the evolutionary tree that reporter Ari Daniel Shapiro recently had the chance to encounter.

SHAPIRO: Usually it’s easy for Louis Deharveng to step outside onto the back doorstep of his lab in Paris, and find the tiny creatures he’s dedicated his life to.

DEHARVENG: Yeah, yeah, there are many, many.

[RUSTLING LEAVES]

SHAPIRO: But today, outside his lab at the National Museum of Natural History, after rooting around in a pile of leaves...

DEHARVENG: Hmmm...usually they are here.

SHAPIRO: He can’t find any. It’s no big deal. It’s just too hot and dry. They’ll be back. So we head inside the lab. Deharveng brings me over to his microscope, and he pours the contents of a small container into a glass dish.

DEHARVENG: OK, we can have a look.

SHAPIRO: He brings the specimen into focus. I gaze down the twin barrels of the microscope.

SHAPIRO: Oh, wow. It’s...

DEHARVENG: Yellow, black.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, yellow and black, curved on itself.

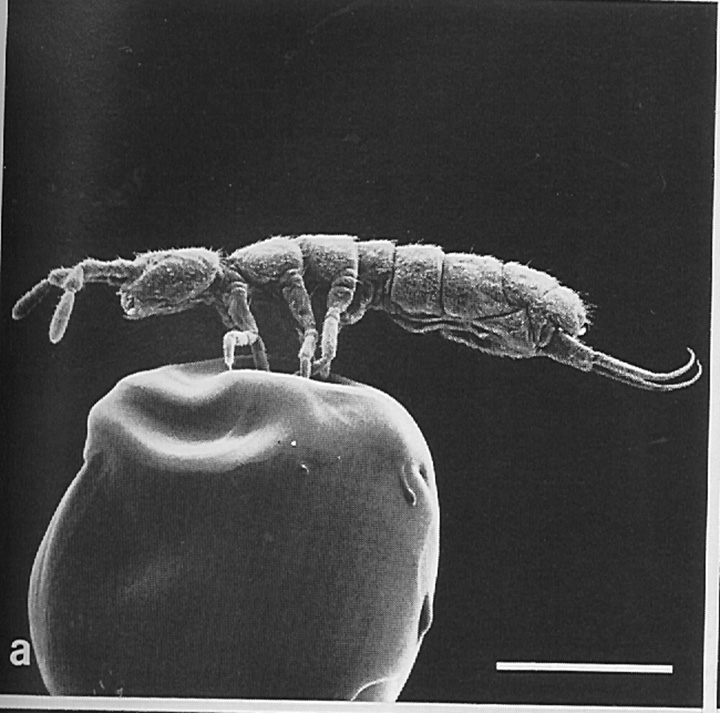

SHAPIRO: It’s got six little legs, a pair of antennae, and it looks like a tiny shrimp or insect.

Springtails get their name from the tail like structure that allows them to spring or jump. (Wikimedia Commons)

DEHARVENG: It was an insect until a few years ago.

SHAPIRO: Meaning that it used to be classified as an insect. Then, around 2000, some DNA work was done on these tiny animals, and they were all re-categorized.

DEHARVENG: It’s not an insect, it’s not a crustacea. It’s a collembola.

SHAPIRO: A massive reclassification like this is common for things like bacteria. But for animals – it’s exceedingly rare. The collembola also go by a more common name – springtails – because a lot of them have a tail-like limb that allows them to spring. To jump.

DEHARVENG: Many collembola have the jumping apparatus, and they can jump many times their own size. And they jump!

SHAPIRO: The feature, though, that really makes a collembola a collembola – is something called a ventral tube. A collembola uses its ventral tube to suck up water, and to attach itself to the ground.

Now, Deharveng hasn’t always been a collembola devotee. When he began his studies as a scientist over 30 years ago, he wanted to focus on beetles. But he couldn’t find anyone who’d supervise a beetle project. So instead, he turned to a mentor who happened to have an interest in collembola. And soon, because so little was known about them, he was hooked.

DEHARVENG: It’s the pleasure to find new things outside in your environment.

SHAPIRO: Is it like looking for little treasures?

DEHARVENG: Yes, we expect to find something but we don’t know what we shall find.

SHAPIRO: Over the last several decades, scientists – including Deharveng – have continuously turned up new kinds of collembola. Right now, there are about 8,000 documented species, and there’s no sign of things leveling off. Collembola are everywhere.

DEHARVENG: They are able to adapt to any kind of habitats. They live from the tropics to the coldest place on Earth – they are in the Antarctic. From the deep caves to the canopy of the trees.

SHAPIRO: Deharveng’s traveled the world in search of collembola. He figures he’s named hundreds of species, and a handful of them have been named after him. Tetracanthella Deharvengi, Gnathisotoma Deharveng i, Paleonura louisi.

And over the years, Louis Deharveng’s seen certain types of collembola fall on hard times. His early work focused on a group of species that used to thrive on a permanent patch of snow in the Pyrenees Mountains between Spain and France. But as the temperature’s gotten warmer, the snow now melts in the summer.

DEHARVENG: I was studying something disappearing under our eyes.

SHAPIRO: More recently, he’s investigated collembola species that live on a single limestone hill in Vietnam and nowhere else. Now that hill’s being blown apart to make concrete, and he’s worried these collembola may well be headed to extinction.

Wherever Deharveng travels, collembola are an important part of a tiny food web of insects and spiders. But he admits that most people have no reason to care about them.

DEHARVENG: They are absolutely devoid of any economical interest. It’s like that.

SHAPIRO: There’s gotta be something that, that matters to you. You’re very passionate about them.

DEHARVENG: Yeah. I don’t like places where there is too much competition. I think competition is not a good way of life. The good way of life is solidarity.

SHAPIRO: Deharveng offered to show me what he meant by solidarity – by introducing me to the people he mentors in his lab. His team comes from all over the world – just like his collembola.

JANION: I’m Charline Janion. I’m from South Africa.

POTAPOV: My name is Mikhael in Russian...Potapov.

XIN: My name is Sun Xin, and I come from China.

BEDOS: My name is Anne Bedos. I work together with Louis about collembola also and different project.

SHAPIRO: I came to visit Deharveng’s lab late in the day. And when I left in the early evening, everyone was still there, working away. Not because they had to, but because they wanted to. People intent on understanding something small about our world, gathered together by a man who cares as much about making a family out of his lab here in Paris as he does about the creatures they all study together.

For Living on Earth. I’m Ari Daniel Shapiro.

CURWOOD: Our story on springtails is part of the series, One Species at a Time, produced by Atlantic Public Media with support from the Encyclopedia of Life.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth