Wolverines at Risk

Air Date: Week of January 12, 2024

Wolverines have big bushy tails and tiny ears. (Photo: Maia C, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Fierce and fuzzy wolverines are in decline, especially in the Lower 48 states where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently designated them as a Threatened species. Wildlife biologist Doris Hausleitner joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how disappearing snow and habitat is affecting wolverines and share the creative techniques needed to study these elusive creatures.

Transcript

DOERING: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently listed wolverines in the Lower 48 as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Despite being fierce scavengers and predators who have been known to take down moose and deer more than twice their size, wolverines are declining across both the U.S. and Canada. And the 300 or so wolverines south of that border are becoming increasingly isolated from each other and from larger populations further north. That’s bad news for genetic flow to connect various populations and improve resilience to things like environmental change, disease, and habitat fragmentation. Here to speak with us is wildlife biologist Doris Hausleitner. Hi there, welcome to Living on Earth!

HAUSLEITNER: Thank you for having me.

DOERING: So I think most of us have heard of Wolverines. But a lot of people just can't picture one. What is a Wolverine exactly?

HAUSLEITNER: Well, that's a great question. Wolverines are more often heard of than seen. And so that's not surprising. I like to think that a wolverine is like a medium sized dog, like an Ozzy Shepherd size. And they have a bear-like face and really long fur, and a really bushy tail. And they run in a funny kind of loping weasel fashion because they are the largest member of the weasel family. And they have exceptionally big feet, which they use to stay on top of snow. They naturally occur at low densities. And they're also quite elusive and don't love to be around humans. And so we don't often see them we often see their tracks.

DOERING: How do you study them if they're so good at avoiding humans?

Wolverines live in extremely remote areas, forcing researchers to travel through the wilderness to study them. Here, Andrea Kortello tracks a wolverine. (Photo: Doris Hausleitner)

HAUSLEITNER: That's a great question. Yeah, we have decided for our project that we want to study them using non invasive means. And so that has been challenging. We do several things. One, we have used non invasive genetic techniques. So we set up a bait station with a lure, and we often set that up in a tree, and we're trying to entice the wolverine to climb the tree to reach for the lure. And while they're doing that, they have to go through these snarls of barbed wire. They have really thick skin. But in the meantime, what they do is they just leave a little bit of hair behind. And the hair is so useful because we can tell first what species it is. And then we can tell what gender it is. And we can tell who it is, so all the way down to an individual. And at the same time as they're going through the barbed wire, we have the bait set up in a way that the wolverine has to stem out with all four legs, and a camera set up across from the bait, taking photos. And each wolverine has a unique chest blaze. And so we can also confirm individual using that chest blaze. And we can tell whether it's a male or female from the genitalia. And if it's a female, we look for signs of lactation. And if they're lactating, we get a little bit more information on reproductive output all in the same time.

DOERING: Wow, that's amazing. So this is like getting pretty up close and personal with the wolverine, but with the help of a camera.

Wolverines are quite good climbers. Researchers take advantage of this by putting bait in trees that puts wolverines in front of a camera, allowing them to get a close-up shot. They also position the bait so that the wolverines must stand on the hindlegs to reach it, allowing the researchers to see their individual chest blaze. (Photo: Andrea Kortello, courtesy of Doris Hausleitner)

HAUSLEITNER: It's a bit intimate. Yes.

DOERING: So I understand that wolverine populations have been decreasing over the past decade or so. Why is this and what threats do wolverines face?

HAUSLEITNER: Yeah, so wolverine have been decreasing over the last decade. And scientists have seen these decreases in population numbers. And in Canada, we've seen this even in areas that are not harvested. So in Canada, we still do have a harvest for wolverine for pelts. But even in parks where there is no harvest allowed, we're seeing a decline. And so we anticipate that the decline is because of an increased amount of recreational users, particularly since COVID. We also have the worry of climate change to add to the decrease in wolverine populations, partly because climate change means less available snow in the mountains, and having less available snow also concentrates recreational users. And so it's sort of a two pronged sword. Snow is needed for denning and for caching food and for moving for wolverines. And we love snow to ride and slide on.

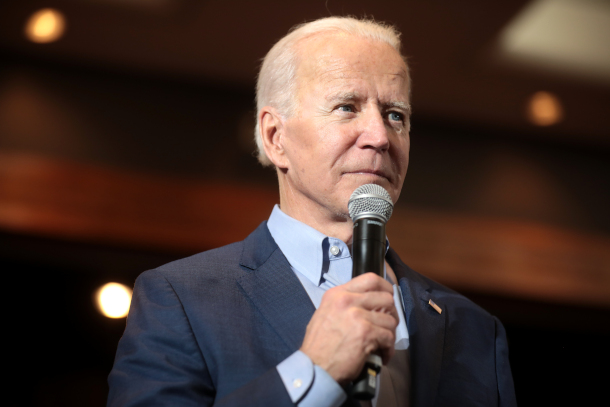

DOERING: Now, the Biden administration here in the US recently listed wolverines as a threatened species. What finally pushed them to do this?

The climate crisis poses a challenge to wolverines who den in snow from February through May to raise their kits. With the snow melting earlier and earlier, denning becomes more difficult. (Photo: Andrea Kortello, courtesy of Doris Hausleitner)

HAUSLEITNER: Yeah, there are a number of reasons they were listed, but the genetic studies that we're doing are showing that there's a bit of a disconnect with genetic flow. And wolverines in the US are really, the populations are really contingent on keeping that genetic flow. Also, there's just more research and more information available on the actual numbers of wolverine. And they're not as good as we had hoped.

DOERING: And here in the lower 48 of the United States, what are some of those numbers currently for wolverine populations?

HAUSLEITNER: Yeah, the estimate is in the hundreds, not the 1000s and more like 300 is estimated. And those numbers are not high.

DOERING: Especially if they're so spread out, right?

HAUSLEITNER: Yeah, exactly. Just having such low densities. You can imagine the impact of even one or two individuals are lost from the population.

DOERING: Yeah, so what can people do to reduce their impacts on wolverines as they enjoy winter sports like skiing?

While the wire on the traps set by researchers may seem harsh, wolverine skin is so thick that it doesn’t cause them any pain. Rather, it snags their fur, allowing researchers to gather a DNA sample. (Photo: Andrea Kortello, courtesy of Doris Hausleitner)

HAUSLEITNER: That's a great question. So people can get familiar with what a wolverine track looks like. And once they get to know a wolverine track, if they cross track, when they're recreating no big deal. Wolverines move all over the landscape. And so if they see sort of a singular track, kind of moving on into the horizon, they should just be thrilled that they saw it, take a photo and enjoy their day. But if they're snowmobiling or skiing, and they come across a concentration of tracks, like tracks that are meandering, moving in and out of rocks, and maybe even tracks of multiple ages, where you can kind of see that the snow has covered some tracks and there's some new tracks, then, that is a good indication that you're in a dining area, because wolverine don't hang around one place for very long unless they're denning. And if you run into that, then the suggestion is to leave that area as soon as possible and stay out of it during the denning period, which is mid February to mid May.

DOERING: And I imagine you know, at a ski resort where there's always a lot of people around this is probably less of an issue, but are we talking about like backcountry skiing, things like that?

HAUSLEITNER: Yeah, correct. Mostly, if you're at a resort, you're the wolverines have probably already moved out of that area. But this is typically for people that are backcountry recreating either mechanized users so that could be cat skiing, or heli skiing or snowmobiling, or non mechanized users which is like snowshoeing or skiing, backcountry skiing, or even cross country skiing.

DOERING: Mm hmm. And what happens when humans move into their territory on skis or on a snowmobile or on snowboards, for that matter?

HAUSLEITNER: You know, wolverines are sort of known for their feisty nature, but they are really, really sensitive at denning areas. And so if wolverine feels threatened at her den, the wolverine mama, she will move her kits. And so that movement is detrimental for two reasons. One, she could be vulnerable to predators while she's moving her kits, she can only move one at a time, so she's to leave one alone. And two wolverine females will provision their den sites prior to denning. And so they will cache all sorts of food items in snow, they use it like a refrigerator. And if they're forced to move, then they don't have access to the parlor anymore. And those food items are harder to come by.

Due to increasing research indicating that the population of wolverines in the U.S. is decreasing, the Biden administration has listed them as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: And Doris, what got you interested in studying wolverines?

HAUSLEITNER: Oh, you know, I always saw wolverine tracks when I was recreating backcountry skiing. And you know, I'd be doing like 10 switchbacks. Wolverine would just be going straight out this mountain and always are in the most wild, beautiful places. They just invoke this sense of awe and wonder that is just so special. That I was I've just been drawn to them. Yeah. Since I was a kid.

DOERING: And have you seen one in the wild?

HAUSLEITNER: I have been so lucky to see a few in the wild. But funny that since I've started this study, which has been over a decade, I have not seen one while I've been on the research project. I've done a lot of tracking, and I've seen a lot of photos and camera traps, but I have never seen one in-person. But I was lucky enough to see some in the wild when I was recreating. I was actually in the Yukon. And I was driving in the middle of the night and the midnight sun and I came over a rise and there were two juveniles wrestling on the middle of the road. And it was I was I was just in shock. It was an amazing encounter for sure.

DOERING: Wow, that's so cool. They were wrestling you said?

HAUSLEITNER: Yeah. And in my mind, I'm totally anthropomorphizing, but I in my mind, their mom had like stashed them away and told them to behave and they had gotten out and decided to wrestle on the road instead.

DOERING: Doris Hausleitner is a wildlife biologist with Seepanee Ecological Consulting. Thank you so much Doris.

HAUSLEITNER: Oh it's been a real pleasure. Thanks Jenni!

Links

Understand the difference between threatened and endangered species.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth