Yucca Mountain

Air Date: Week of February 8, 2002

The Department of Energy recently announced it will push ahead with plans to build a high level nuclear waste site at Yucca Mountain in Nevada. State officials and environmental groups oppose the plan. But as Jon Christensen reports, many residents who live closest to Yucca Mountain have grown fatalistic about living in a nuclear environment.

Transcript

CURWOOD: The new White House budget calls for five and a half million dollars to prepare Nevada's Yucca Mountain for nuclear waste disposal. Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham says he's pushing ahead with a plan to build a high level radioactive waste repository at the desert site, ninety miles north of Las Vegas.

Nevada's Congressional delegation, and a broad coalition of environmental groups, firmly oppose the idea and a battle is looming in Washington. But, as John Christensen reports, some folks who live in the shadow of Yucca Mountain have grown a bit fatalistic about living in a nuclear landscape.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

CHRISTENSEN: Yucca Mountain's reputation looms large in Southern Nevada. But, even from nearby Amargosa Valley Yucca Mountain is hard to pick out among the jumble of low lying ridges on the eastern horizon. Amargosa means "bitter" in Spanish. The name is taken from the Amargosa River, which is really not much more than an ephemeral creek in some places, a dry wash in most that drains toward Death Valley to the west. So, it is something of a surprise to find a small farming community thriving in this vast, desolate place.

[COW MOOS]

GOEDHART: We like to say it takes a real farmer to be a farmer within the shadows of Death Valley National Park. Someone who has has a little bit-a little bit crazy, I guess.

CHRISTENSEN: Ed Goedhart stands on the edge of an emerald green field, while a giant center pivot sprinkler slowly turns around a circle. Goedhart is the manager of the Ponderosa Dairy, home to six thousand cows. He points to the site of the proposed nuclear repository.

GOEDHART: Yucca Mountain will probably be about fifteen or twenty miles north of where we are right now.

CHRISTENSEN: Goedhart wears a t-shirt that says, "Yea, though we live in the shadows of Death Valley and Yucca Mountain, we will not fear. We will be happy, make milk and prosper." But he is more concerned than the bravado on his back might suggest. The Ponderosa Dairy produces thirty-two thousand gallons of milk a day. The organic milk is distributed throughout the southwest. The cows are fed hay grown here in Amargosa Valley on fields irrigated with water from the same aquifer that runs under Yucca Mountain.

GOEDHART: At the point in which the Yucca Mountain went through, if there was a problem with, say the containers leaking nuclear waste, there would be a concern that it could migrate down and hit the water table.

[SOUND OF TRAM]

CHRISTENSEN: A journey into Yucca Mountain begins at the entrance to a tunnel where a tram waits to carry workers into the dark depths where the U.S. Department of Energy plans to entomb the nation's deadliest nuclear waste forever.

A tram waits at the entrance to a tunnel to carry workers into Yucca Mountain.

A tram waits at the entrance to a tunnel to carry workers into Yucca Mountain.(Photo: Jon Christensen)

KOVACH: Make sure you keep your arms inside because we've got some walkways on mine power centers that stick out. So, just keep your arms in.

CHRISTENSEN: Richard Kovach, the construction manager for Yucca Mountain, is our guide. This five mile tunnel is the home of some of the last studies that are being conducted to try to determine whether the mountain can safely contain spent fuel from commercial nuclear reactors, and high level radioactive waste from atomic weapons plants.

The Energy Department has spent almost four billion dollars studying Yucca Mountain, making it the most intensively scrutinized piece of ground on the planet. The initial attraction was obvious. Yucca Mountain is on the edge of the Nevada test site, not far from where hundreds of atomic bombs were exploded above and below ground between 1951 and 1992. Less than four inches of rain a year falls on this bone dry ridge, made of ancient volcanic ash laid down thirteen million years ago. But, what scientists have found inside Yucca Mountain has been surprising: water.

KOVACH: And that's the issue here at Yucca Mountain, is the movement of water from the surface down through the potential repository, down into the water table. And then from the water table where it goes from there. Because the water table moves from the north to the south, it goes into the Amargosa Valley which is populated.

CHRISTENSEN: Inside the tunnel it is cool, dry and dusty. But, there is water trapped in tiny pockets in the matrix of the volcanic rock. And water slowly percolates down through fissures and faults in Yucca Mountain. The tram descends about a mile down a gradual slope that takes us to the very middle of the mountain not far from where the waste would be stored.

[SOUND OF MACHINERY]

KOVACH: At that point we're about seven hundred feet from the water table, and about the same distance from the surface. The potential repository is in that direction.

CHRISTENSEN: The tram has stopped at a side tunnel where mock waste canisters, heated by electricity rather than radiation, have been installed to simulate what will happen inside Yucca Mountain when real radioactive waste is stored here.

KOVACH: You can see the heated drift, there's nine simulated canisters. The canister temperature is 392 degrees; it was pretty close 200c. So, they're simulating in eight years what if we were to go to a hot repository, what we would see in maybe a thousand years.

CHRISTENSEN: The Energy Department predicts that no one will be harmed by any leaking radionuclides for hundreds of thousands of years. That prediction is based on a computer model called a Monte Carlo Simulation, that combines all of the data from these tests in every possible way to determine a range of possibilities of what will happen inside the mountain: How fast water will drip onto canisters. How fast the canisters will corrode. How much of the radioactive waste will be absorbed by the rock. And how much will leak down to the water table.

The Energy Department says its canisters, made of a high tech metal alloy, will last for at least ten thousand years. By that time much of the most dangerously radioactive material will have decayed. And when the mountain eventually leaks, it will be diluted enough not to be hazardous.

(OUTDOOR SFX)

KOVACH: It looks like some bums or somebody come in-See, these were all stacked up over here, and this is not like this. Somebody's come in and probably spent the night and used these mattresses here....

CHRISTENSEN: About twelve miles away in Lathrop Wells, Jim Hooton owns the closest place to Yucca Mountain. It is a couple of acres of desert scrubs scattered with surplus equipment scavenged from the Nevada test site.

[SOUND OF METAL]

HOOTON: They put this stuff up for bid. And I bid on electronics and computers. And these are little houses that they had for air sampling and monitoring devices.

CHRISTENSEN: There's not much around Hooton's junkyard. Two gas stations, a small restaurant, bar and store, and a brothel are all of Lathrop Wells. But, Hooton has high hopes. If radioactive waste is going to be buried here, local county officials want to build a science and technology center at this crossroads to take advantage of the enduring notoriety Yucca Mountain is likely to bring to Amargosa Valley. And Hooton's place sits right in the middle of the plan.

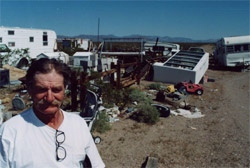

Jim Hooton owns the closest place to

Jim Hooton owns the closest place toYucca Mountain, a junkyard in Lathrop Wells.

(Photo: Jon Christensen)

HOOTON: And the economic development that's going to go on in this area in the future is going to be pretty good, from what I understand. As far as them developing Yucca out there, I think it's probably, in my opinion, the best place to put it. And it's already been messed up for the next twenty thousand years, so why put it someplace else in somebody else's backyard, you know?

CHRISTENSEN: Hooton worked out at the Nevada test site for twelve years as an electronic technician preparing for atomic bomb test. Like Ed Goedhart, he wears a Ponderosa Dairy t-shirt proclaiming he has no fear. And he means it.

HOOToN: You know, we've been living here under the shadow of a test site for years and years and years, and we've had no problems. Nuclear energy is just like a gun; it's only as dangerous as the human being with his finger on the trigger, you know. That's my opinion.

MCCRACKEN: People in rural southern Nevada area around the Nevada test site have had experience historically with nuclear technology. I mean, the-- We used to get up in the morning and watch the a-bombs go off.

CHRISTENSEN: Local historian, Robert McCracken, has conducted oral histories with dozens of residents of Amargosa Valley and other small towns surrounding the Nevada test site. He says many residents view the location of a national high level radioactive waste repository at Yucca Mountain as another challenge to be met for the good of the whole country, as well as a boon for the local economy. Here he reads from the conclusion of his book, "The Modern Pioneers of Amargosa Valley."

McCRACKEN: The new pioneers in the Amargosa Valley believe that nuclear technology and the desert, with its freedom and incredible beauty, can co-exist productively and harmoniously.

[COW SOUNDS]

CHRISTENSEN: But out at the Ponderosa Dairy, Ed Goedhart is not so sure.

GOEDHART: I really can't make a prediction how they're going to implement this, and what impacts it could have. I mean, so it's kind of tough to say. I think we can live with it, but who knows.

[COWBELL, WHISTLING]

CHRISTENSEN: No one can be sure whether Yucca Mountain can contain the radioactive waste long enough for it to be rendered harmless. A recent report by the independent Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board said scientific uncertainties make it impossible to ensure the safety of the site. But, the Energy Department is pressing ahead with the project. The state of Nevada now has an opportunity to voice its objections. But, the ultimate fade of Yucca Mountain will be in the hands of Congress.

For Living on Earth, I'm John Christensen in Amargosa Valley, Nevada.

[MOOING]

[MUSIC: Mike Oldfield, "The Lake"]

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth