Preserving Languages

Air Date: Week of March 22, 2002

In the United States, a number of Native American languages are in danger of becoming extinct. Clay Scott looks at two tribes—the Crow and the Blackfeet that are trying to keep their languages alive and pass them on to the next generation.

Transcript

CURWOOD: As many as 6,000 languages are spoken in the world. And nearly half of them are in danger of extinction. The disappearance of a language is the loss of a unique system of communication. But, it also means the loss of a culture, an expression of human experience.

In the United States, of the 300 or so Native American languages spoken before the arrival of Europeans, half are already gone. Most of the rest are vanishing fast. But, there's a movement to revitalize tribal languages. Clay Scott reports.

SCOTT: The Crow Indian Reservation sprawls over two and half million acres of mountains and high plains in Southeastern Montana. In the center of the reservation is the town of Lodge Grass. The community school, a combination elementary and high school, sits on a hill overlooking the Little Big Horn River in the Wolf Mountains beyond. In many ways, Lodge Grass is much like any other American school. But there's no mistaking that this is a Crow school. Along the corridors, posters and inspirational sayings remind the children that they are a unique people with a unique culture, history and language.

[SOUND OF CHILDREN IN SCHOOL]

SCOTT: Between classes, the hallway chatter is in both Crow and English. But while most teachers are more comfortable with Crow, the students speak only in English. And that mirrors a growing problem on the reservation as a whole. Plenty of people speak the language, but very few young people speak it. Mary Helen Medicine Horse, the school's bilingual director, worries that an entire generation may be losing its language.

MEDICINE HORSE: Well if we don't bring it back now, today, then in the future they're going to lose it all together, the language and the culture.

SCOTT: As recently as the 1960s, more than 80 percent of Crow children spoke the language. Today, say teachers here, that figure is closer to ten percent. And even children who are fluent, typically those raised by grandparents, are often reluctant to speak Crow outside the home. At Lodge Grass School, and elsewhere on the reservation, teachers are trying to reverse that trend.

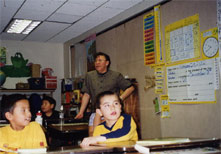

Suzie Bird in Ground, teaching

Suzie Bird in Ground, teachingCrow. (Photo: Clay Scott)

[CHILDREN LEARNING CROW]

SCOTT: In this third grade class, teacher's aide, Suzie Bird In Ground, is going over colors and numbers in Crow. As part of the school's fledgling bilingual program, fluent Crow speakers spend half an hour twice a week with students of all ages. What Suzie hopes to convey to the children, she says, is that the language is more than mere words; that it cannot be separated from who they are, and where they live.

BIRD IN GROUND: We want the kids, the students, and the Crow young people, to learn it because it's such a beautiful language. And it goes with everything, the land, what it is here. Crow country, it's got names for everything, places, and rivers, and the constellations. And, it's all in Crow. And the students and young people need to know that.

[CHILDREN LEARNING CROW]

SCOTT: But an hour a week is not enough to create real fluency. And despite growing awareness of the problem, the number of young Crow speakers continues to plummet. There are many reasons for the decline. Increased marriage outside the tribe, for example, as well as a prevalent feeling on the part of some parents that children who concentrate on English are more likely to succeed in the outside world. But the biggest factors, say many Crows, is the encroachment of mainstream American popular culture--from TV, to music, to sports.

[HIGH SCHOOL BASKETBALL GAME, CROW CHEERLEADERS, RAUCOUS CROWD]

SCOTT: Tonight, over a hundred Crows have driven to the town of Laurel, Montana for a high school basketball tournament. One of the reservation teams, the Plenty Coups Warriors, is playing Fromberg. In the Crow rooting section, emotions run high. War cries erupt at every Crow basket, steal, or blocked shot.

Cheering as loudly as anyone else is Dr. Russell Stands Over Bull. At halftime, standing outside the gym, he talks with pride of the young Crows' success on the basketball court. But, even that, he says, comes at a price.

STANDS OVER BULL: I can guarantee you that it's not cool today to speak the language amongst the youth. They look at Michael Jordan. They look at the latest hip hop artists. And, they don't see natives on the billboards. They don't see natives on MTV. But the culture that's coming in is forcing a lot of the young ones to really assimilate into the mainstream society. And to assimilate, in their mind, is to let the language go.

SCOTT: Without enough young speakers, it's extremely difficult for any language to regenerate itself. And while the Crow language is still far from reaching the point of no return, several neighboring tribes seem to have already passed it. Languages like Assiniboin, for example, or Gros Ventre, are close to extinction with no more than four or five elderly speakers each.

Until recently, many people put the Blackfoot language in the same category. But in the town of Browning, Montana, along the east front of the Rocky Mountains, a revolutionary experiment is taking place.

[TEACHER AND CHILDREN IN CLASSROOM]

SCOTT: This is the Nitzipuhwahsin, or "Original Language School," a privately funded language immersion school. Here, 36 children from kindergarten through eighth grade learn almost exclusively in the Blackfoot language. A sign in the entrance, in Blackfoot and in English, reads "Please do not speak English here."

The school's ambitious goal is to create a new generation of young people fluent in their ancestral language. One of those young people is thirteen year old Jesse Durocher, who wears his black hair in traditional braids. I asked him why he's learning Blackfoot.

DUROCHER: Well, everybody should be unique. And, if we don't have a language, then we're just like everybody else. They wouldn't know that we're Blackfeet because we didn't speak our language no more. We just speak English. And, I want to keep our language going. It's been dying off. And I want to keep it going so it doesn't die off like some other reservations. They don't got their language no more. And I just want to pass it on, and try to keep it going.

Jessie Durocher is learning Blackfoot

Jessie Durocher is learning Blackfootat the Nizipuhwahsin language immersion

school. (Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: The founder of the school is Darrell Kipp, a Blackfeet who spent most of his adult life away from the reservation. After a tour in Vietnam, a Master's degree from Harvard, and another from Goddard College, he finally got homesick, he says. But when he returned, he found the language of his childhood was dying. He decided to try and do something about it, despite lack of funding, and despite surprising resistance from many of the Blackfeet themselves who told him it was a waste of energy.

KIPP: Someone's going to say to you, "Well, why would you want to speak Blackfoot, or relearn it? They don't speak it in Great Falls. They don't speak it in New York. They don't speak it at the universities." I think that's really missing the point entirely. If it speak well in my own soul, then that's really what it's about.

Darrell Kipp in office, Browning,

Darrell Kipp in office, Browning,Montana. (Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: Creating fluent young speaker where none exist is no easy task. Teachers need to be trained. Textbooks need to be developed. Then there's the issue of how to bring a tribal language like Blackfoot into the present while respecting its past. Shirley Crow Shoe, one of two full-time teachers at the school, says she feel free to coin new words and expressions. But, each new addition to the language must first be approved by tribal elders.

CROW SHOE: Look at all this technology. Computer. We have to find a word, a Blackfoot word for computer, fax machine, microwave. All this modern technology, we're making up words. We had to explain to the elders what a computer does. And one of the things that they said was, as you write, as you're writing, it comes back in a rapid form, something like that.

SCOTT: How do you say that in Blackfoot?

[CROW SHOE SPEAKS IN BLACKFOOT]

SCOTT: The Nitzipuhwahsin School may be small. But it's already had an effect far beyond the boundaries of the Blackfeet reservation. Members of dozens of tribes from around the country have come to visit the school. And many are planning their own language immersion programs. Darrel Kipp says there's a revolution underway in how young Native Americans view themselves, their history, and their language.

KIPP: They'll simply not be carrying the excess baggage and the prejudices that we had to get rid of first. They'll develop their own dialects. They'll develop their owns ways and styles of speaking. They're going to develop their own idioms. They're going to develop all of these things in our language. And they're going to refresh our language.

SCOTT: But not even Darrell Kipp believes the Blackfoot language will ever replace English on the reservation, or even that a majority of Blackfeet will learn to speak it again. When the children walk out the doors of the school, they enter an English-speaking environment. In fact, of more than 10,000 people on the reservation, only 25 or so fluent speakers remain. Many of them spend their afternoons at Browning Senior Center, sitting in the corner unfolding chairs, telling stories in quiet voices. Robert Many Guns comes here almost every day to speak the language he fears is about to vanish.

MANY GUNS: It's getting pretty near. It's getting just a little ways from us. And then, it'll be too late. Because right now, we have a handful of elders, from 60 to 65, my age. We're the next group. But it's just skimpy in there. Some people can understand. That's what I'm talking about. They can understand, but they can't speak. The next generation after him, there's not going to be nothing.

SCOTT: The elders are a crucial resource in the fight to retain the language. While they applaud the efforts of the teachers at the Nitzipuhwahsin School, they say something is missing. The language the students are learning to speak still sounds foreign to them. It doesn't have the richness and depth of the language they, themselves, learned from parents, grandparents, great grandparents.

The kids can say a lot of words, says Robert Many Guns, but they don't put them together right. There's a gap of more than 50 years between the last generation of fluent speakers, and the pioneering efforts of Darrell Kipp's school. The only way to bridge that gap before it's too late, says Robert Many Guns, the only way for Blackfoot to be passed on is for the children to spend time with the old people, sit quietly, and just listen.

[MANY GUNS SPEAKING BLACKFOOT]

SCOTT: For Living on Earth, I'm Clay Scott in Browning, Montana.

[MUSIC: Steve Roden, "Straight Arrow (Navajo Prayer)," IN BETWEEN NOISE (Inverted Tree Projects - 1993)]

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth