High Tech Booty Hunt

Air Date: Week of January 3, 2003

When former President Clinton declassified the global positioning system, also known as GPS, it opened the door for citizen use of the satellite navigation network. As Ken Shulman reports, a new sport called geocaching has sent both outdoor enthusiasts and techno-geeks on treasure hunting adventures using handheld GPS devices.

Transcript

CURWOOD: When President Bill Clinton declassified the global positioning system people expected folks like farmers, environmental monitors and mapmakers to take advantage of the technology. Yet, none of these applications seem as creative, or delightfully frivolous, as geocaching – a new treasure hunting sport that uses the computer, the World Wide Web, and GPS. As Ken Shulman reports, geocaching is catching on all over.

[SOUND OF HIKING]

XANATOS: We're right on top of it now. It's probably in here some place.

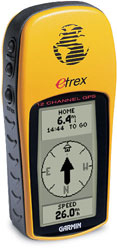

SHULMAN: Here, at the foot of Mt. Tom in central West Massachusetts, the mercury cowers just below the 15 degree Fahrenheit mark. There must be something very valuable, very precious, to lure us out onto the slippery, ice-crusted snow, three miles off the nearest road. The arrow on Dave Xanatos' handheld GPS device points due north. The numbers on the display tell us that we're close.

XANATOS: Wait, wait a second. I found it. I got it, it's right here.

SHULMAN: Found what? Xanatos tugs a green metal ammunition box out of its hiding place and sets in on a rotted birch log. The self-employed web designer undoes the latch and opens it.

XANATOS: Ah, a spine key chain. From Family Chiropractic. Dr. Michael Gleil... Aluminum shafts, no doubt for darts, I guess, or something like that. A yo-yo. A little, some sort of poke the thing game. An AOL disc. That can't really be an AOL disc. Oh how cheap. Someone put an AOL disc in here. That's bad!

[QUIET SOUNDS OF TALKING IN BACKGROUND]

SHULMAN: One week after President Clinton lifted the GPS ban, a GPS enthusiast in Oregon placed a slingshot, a can of beans, and some software in a five gallon plastic bucket, hid the stash, and posted the GPS coordinates on the web. And geocaching was born. There are almost 13,000 caches posted in 107 countries. There are caches on the side of a dormant volcano in southern Russia and others in undersea grottoes. Websites like www.geocaching.com offer listings, along with cache descriptions, photographs, and clues for novice hunters.

XANATOS: I'm going, at this point, to put everything back in.

SHULMAN: Xanatos signs our names in the logbook and takes our photographs with the disposable camera. He takes the spine key chain, and leaves a Hot Wheels race car and some of his business cards as barter. He hasn't gotten any clients this way, he says, but hey, you never know.

[SOUNDS OF PUTTING BOX BACK]

XANATOS: So now, I'm putting it back right where it was and I will camouflage it effectively.

SHULMAN: Then he conscientiously returns the box to its hiding place for future geocachers to find. Geocaching is, in his own words, one of the best things to happen to geeks in a while, because it gets them out into nature.

[SOUND OF HIKING]

XANATOS: I mean look at this, we've been battling the ice and it's cold and we have beautiful trees and sunlight all around us and everything. No computers in sight really to speak of.

SHULMAN: Isn't there one in your pocket?

XANATOS: Yeah, but that doesn't count. It's not on right now. [Laughing]

[SOUND OF CHILDREN]

SHULMAN: Geocaching doesn't just bring out the kid in adults. It also brings out the kids.

[SOUNDS OF CHILDREN]

SHULMAN: These cub scouts, troop 702 from Reading, Massachusetts, are on their first geocache hunt. The terrain is a gentle hill two hundred feet above the parking lot at Hogue Pond in nearby Winchester. It doesn't sound like much of an adventure. Yet there is something magical, says Adena Schutzberg, one of the supervising adults.

SCHUTZBERG: Well I think the best thing for me, I'm trained as a geographer, is it takes me to places I otherwise wouldn't go. Sort of an excuse to get out and find a new place that somebody else has decided is somehow is significant or important to them. So it's a great way to see your local area. I grew up about two miles from here and I've never been here in my life so there you go. That's the perfect example.

CHILD: Oh a calculator, excuse me, excuse me, a beach ball, yeah.

SHULMAN: It appears that most school-age geocachers do it for the trinkets, while most grown up geocachers get their kicks from using their high tech toys, toys that are surprisingly affordable and easy to use.

[SOUND OF CHILDREN]

SHULMAN: A hand held GPS device costs as little as $100 and can be mastered in about five minutes. Bob Hogan is an engineer, and one of the first geocachers in Massachusetts. He's the leader on this cub scout outing. One thing geocachers of all ages have in common, he says, is that they expect, and usually get, a very quick fix.

(Photo: ©Garmin Corp. 2001)

[SOUND OF CHILDREN]

HOGAN: Most of society still requires semi instant gratification. And if you can't get people to a cache, the majority of the people, within forty-five minutes to an hour, chances are they may not want to go out and do it.

CHILD: See we got a calculator. Now daddy has a new one and so do I.

SHULMAN: While geocachers will undoubtedly benefit from even twenty minutes in the woods, there are those who worry about the impact this low key hi-tech odyssey might have on public lands and parks. Tom Casey is head of law enforcement at Minuteman National Park in Concord. The park includes important sites and artifacts from the American Revolution. Casey recently discovered, through an internet search, that at least one geocache has been set in his park. And he's concerned about the consequences.

CASEY: We have rock walls that have been here since 1775 and in some instances they could have been used by the local militia to fire at the Brits, and if someone removes rocks to hide a container inside a rock wall or to build a cairn as a marker for where it might be, all those items could drastically change the complexion of the park..

SHULMAN: At present, geocaching is illegal in national parks. Casey does concede that specific national parks, and specific park superintendents, might eventually issue permits to allow limited supervised geocaching if the demand should grow. And it well may.

[SOUND OF HIKING]

SHULMAN: Geocaching is easy, it's fun, and can be done at all levels of ability and age. Like the worldwide web, it creates a mysterious, benign connection among people who may never meet, but who share in the experience of a special place. And of a special time, a time of memory, when finding a chest that someone has stocked with treasures and hidden for us to seek was all that really mattered in the world.

HOGAN: We're in business, boys.

SHULMAN: For Living on Earth, I'm Ken Shulman, in Winchester, Massachusetts.

HOGAN: There it is. Yeehaw. All righty, let's see what he wrote here. One of those little Chinese checkers type games, some fishing lures, more golf balls. Top Flight...

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth