Overflowing Artifacts

Air Date: Week of September 19, 2003

By law, any public lands set for construction projects or oil or gas exploration must first be open to archaeological examination and, if necessary, excavation. In the Southwest, these excavations are yielding all sorts of historical treasures. But archaeologists and area museums are running out of space to store these artifacts. Ken Shulman has the story.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The philosopher George Santayana once wrote that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. But history can also become too much to handle. Especially if you are working in archaeology in the American Southwest these days. As more and more highways and homes are being built, archaeologists are unearthing an ever-increasing collection of artifacts. And as Ken Shulman reports, they are running out of places to put it all.

[HIGHWAY SOUND]

SHULMAN: The Pojoaque corridor is one of the ten most dangerous roads in the United States. Accidents are common on this two-mile spread of asphalt fifteen miles north of Santa Fe. In 1999, the state of New Mexico allotted $8.8 million to redesign the artery and widen the roadway. Before construction began, researchers from the Museum of New Mexico excavated four sites along the corridor.

MOORE: We’re finding prehistoric shards typical of Spanish sites….

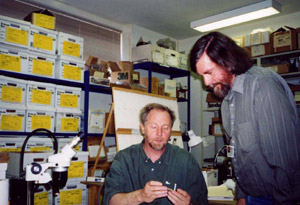

SHULMAN: Jim Moore is a project director in archaeology at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe. Here in the museum’s research laboratory, he supervises four researchers as they examine, catalogue, and bag the artifacts from the Pojoaque corridor. It will take close to a year to process the 150,000 arrowheads, stone tools, and potsherds recovered from the highway project. But Moore isn’t worried about the pace. He’s worried about space. Storage space.

Jim Moore (right) discusses findings from the Pojoaque corridor with a researcher. (Photo: Ken Shulman) Jim Moore (right) discusses findings from the Pojoaque corridor with a researcher. (Photo: Ken Shulman) |

MOORE: We don’t know if the repository will actually be able to accept this entire collection because they are running out of space. Boxes of artifacts take up a lot of space when they’re stored. They’re supposed to be properly prepared and curated in perpetuity, on projects like this.

SHULMAN: There are lots of construction projects in New Mexico and across the southwest. In the 1950s, it was massive highway construction. Today, it’s oil and gas exploration. By law, contractors working on public lands must assess, and if necessary excavate, any archaeological sites that might be disturbed. These excavations yield all sorts of Indian, Spanish colonial, and Santa Fe trail era treasures. They aren’t all the kind of treasures you’d expect to see in museums. Moore estimates that fewer than one tenth of one percent of the objects he examines are of display quality. MOORE: Frankly, we make our living looking at people’s trash, and you don’t usually throw out good things. So, we’re looking at broken objects and stuff that had seen the end of its useful life. SHULMAN: Just because a thumbnail-sized glazed pottery chip might never make it to the display case doesn’t mean it can be tossed into the dumpster. For archaeologists, these fragments are priceless nuggets of information, to be cherished, studied, and then carefully stored so they can be studied again by future researchers. And storage wasn’t always a problem. According to Duane Anderson, associate director of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, museums used to compete to see who could house the most artifacts. ANDERSON: Because there was a lot of stature and prestige in that. But then, when people became more concerned about the quality of space and curation, how things were cared for and climate-controlled conditions and the cost of all that, why all of a sudden there’s been a reversal. And now it’s almost, as in the case of Colorado, they’re saying we can’t take anymore. SHULMAN: Unlike Colorado, the other southwest states haven’t closed their doors. But New Mexico is getting close. Thirty years ago, New Mexico archaeologists had excavated about 13,000 sites across the state. Today that number has increased ten-fold. There are approximately 10 million artifacts in the museum’s repositories. Part of the collection is stored in a damp, dark basement in central Santa Fe, in what once was the city morgue. The rest is stored here, in the basement of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture on the south side of the city. [SOUND OF ROLLING SHELVES] SHULMAN: In the Prewitt House, the museum’s basement repository, rolling high-density shelving maximizes the 8,000 feet of storage space. This facility is named after the company that built most of New Mexico’s highways in the 1950s and 60s, and whose work created the first wave of excavations and artifacts. Conditions here aren’t bad. Temperature and humidity levels are relatively stable. Unlike the former morgue, Prewitt House has no exposed plumbing or heating ducts. It’s not perfect, says Julia Clifton, curator of archaeological collections at the museum. But it’s a big improvement.  Julia Clifton with a box of artifacts in the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture. (Photo: Ken Shulman) Julia Clifton with a box of artifacts in the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture. (Photo: Ken Shulman)

SHULMAN: The high-density shelving did buy Clifton and her colleagues a little time. But it didn’t buy them any more space. At current rates of accumulation, about 500 cubic feet of artifacts per year, the Prewitt House will be completely full by the end of 2006. And that’s only if the pace of excavation remains constant. Steven Fosberg is state archaeologist for the New Mexico Bureau of Land Management. He says that oil and gas drilling in New Mexico is bound to increase. And as energy needs expand, so will excavations. FOSBERG: We haven’t gotten to the point where, because of the lack of curatorial facility, we basically were unable to carry out the type of excavations that we want to. I wouldn’t say we’re at that point yet. But we are at the point where we’re going to have to, I believe, make some long-term planning decisions about how we face this curation crisis. SHULMAN: There are plans under consideration to build a $7 million storage facility in Santa Fe. The facility, if built, would give the state a ten- or twelve-year buffer before it, too, reached capacity. As an alternative, Fosberg has proposed converting Fort Wingate, a recently abandoned military base in Gallup, New Mexico, into a mega-repository for all the southwest states. The idea is promising. It’s also expensive. Repositories for stone tools and potsherds tend to lose state budget battles to more glamorous projects like museums, galleries, and theaters. The only thing that seems certain is that the flow of artifacts will thicken. And that while everyone agrees that New Mexico’s past is important, no one seems to be able to agree what to do with it. For Living on Earth, I’m Ken Shulman in Santa Fe, New Mexico. [MUSIC: Al-Jabra “The Rise and Fall” THE HEREAFTER (No Label - 2003)] Living on Earth wants to hear from you!Living on Earth Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth! NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

|