A Brand New Bird

Air Date: Week of October 17, 2003

For years, bird breeders in Europe were fixed on breeding the perfect singing canary. They later shifted to breeding for the most brilliant plumage. And in the late 1920s, two German bird breeders decided to take this goal one step further. Host Steve Curwood talks with author Tim Birkhead about the quest to breed the first red canary.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Back in the 1920s, Hans Duncker, an amateur bird breeder was walking down the streets of Bremen, Germany when he heard something that stopped him in his tracks. It was a nightingale song, but it was the wrong place and the wrong season for a nightingale to be singing. Turns out a canary breeder, Carl Reich, was exposing his birds to nightingale songs and eventually, these canaries had started singing like nightingales.

The idea started Herr Duncker thinking, and he set out with Carl Reich to try and alter another aspect of the canary – its color. By hybridizing, or breeding the canary with another species of bird, in this case, the red siskin, they hoped to create the world’s first red canary.

|

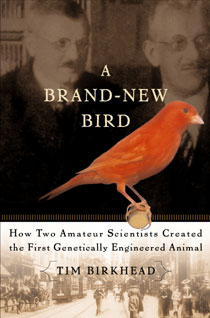

Tim Birkhead has written a book about this quest called “A Brand New Bird: How Two Amateur Scientists Created the First Genetically Engineered Animal.” He joins me now from the University of Sheffield, in England. Tim, welcome.

BIRKHEAD: Hello. CURWOOD: Now, Tim, this is a pretty strong claim that you make in the subtitle of you book. How is it that the red canary is the first genetically engineered animal? BIRKHEAD: A lot of people think that a genetically engineered animal is one that’s been produced since the kind of human genome project. But the red canary was the first genetically engineered animal because it happened a long time ago in the 1920s. The red canary is actually what we would call a transgenic animal. It’s got the genes of another species inside it. Basically, the red canary is a canary with the genes of something called a red siskin, a little South American finch in its genome. CURWOOD: Why did Herr Dunker and Reich decide on a red canary as their goal? BIRKHEAD: There were two strands that, I think, came together to create this. First of all was a story that Karl Reich told, which was a well-known story in canary breeding circles, about an event that happened in Britain in the 1870s. Bird shows, particularly canary shows, were incredibly popular at that time. And at this particular show, a certain Mr. Edward Bemrose turned up with canaries that were the color of marigolds, and he won every prize going. And the secret was simply by feeding your canary on red peppers during the time that it was molting. The color from the red peppers somehow changed the color of the feathers from yellow to orange, but certainly not red. So, that was the first strand. The second strand was when Hans Duncker met a wealthy Bremen businessman, Consul Karl Cremer. And Cremer was somebody who was obsessed by caged birds. And when Duncker went to see him, one of the little birds that Cremer had was something called the red siskin from South America. The Spanish, who had imported the birds to the Canary Islands, regularly hybridized the red siskin with the canary. And as soon as Duncker heard this, he felt that any fool could feed a bird on red peppers. There was no skill in doing that, but he certainly had this vision that if he could capture the genes that would turn a canary red, now that really would be something. And the idea was that they would hybridize the red siskin with ordinary yellow canaries, they would back-cross those to ordinary canaries over several successive generations, whittling away everything that they didn’t want from the red siskin, but retaining the red genes. And they do this buy simply keeping the reddest birds. Of course, hybridization was extremely widespread. People had been doing that for a long time, particularly in the bird breeding world. What makes this project particularly striking is that Duncker wasn’t satisfied with just hybridizing the red siskin with the canary. What he wanted to do was just to get the genes that made the plumage red. And so an explicit part of his project was this business of back-crossing the hybrids with canaries and getting rid of all those unwanted genes. So he had his mind focused very clearly on just those one or two genes that made the red siskin red and getting those into a canary. That’s what makes this a special transgenic animal decades before its time. And Duncker predicted that after maybe four or five generations they would have red canaries. CURWOOD: Now, this story is all taking place in the late 1920s when Germany is having its difficulties. And eventually, in the 30s, Hitler comes into power there with the Third Reich. What impact did Hitler’s regime have on the world of canary breeding? BIRKHEAD: The rise of the Nazis in Germany coincided with the time when Hans Duncker was actually losing interest in the red canary project. He tried breeding his hybrids – he succeeded in producing hybrids – he tried back-crossing them. The trouble was that they weren’t red. Now when he’d done his initial crosses between different colored canaries, green canaries and yellow canaries. What he found was the green color, which is the color of the wild canary, was always dominant over the yellow color which was recessive. And as a result, if he crossed a green canary with a yellow one, invariably the offspring were green. He assumed that exactly the same thing would be true when he crossed the red siskins with ordinary yellow canaries. But it wasn’t. And that was almost certainly because he didn’t realize how complex the genetic mechanism was. So all he could achieve were these bronze, coppery-colored birds, so he started to lose interest by about 1930. And this coincided with the rise of the Nazi regime. Interestingly, because Duncker was a school teacher and because he was an expert in genetics, that made him extremely attractive to the Nazis. And they were very keen to get him on board. And Professor Hubert Walter of the Bremen University had kind of identified Duncker’s Nazi role and singled him out and said he was a disgrace to biology because he had helped to perpetuate some of the Nazi views. And I was extremely disappointed because prior to this I had imagined setting Duncker up as a kind of genetic hero. Nonetheless, I’m sure this colored the way other people saw him and why Duncker’s pioneering work in these genetically modified birds eventually disappeared into obscurity. CURWOOD: You write that there was a crucial turning point in the red canary saga involving our understanding of how genes work. Could you outline this for us please? BIRKHEAD: The turning point happened in North America about 10 or 15 years later. Charles Bennett was a research physiologist, keen bird breeder, and interested in these orangey-colored canaries. And he’d imported some from Germany. Then he was reading a medical journal and came across a very bizarre account of how several women had lived on a diet of carrots for several weeks, and they’d all turned a deep orange color. And this gave him the idea of feeding carrot extract to some of his orange canaries that he’d had from Germany, but also some of his regular yellow canaries. When he gave the carrot extract to the yellow canaries, and waited for them to molt, there was virtually no effect. The feathers re-grew almost exactly the same color. But when he fed the carrot extract to the orange canaries, the new feathers came through an even darker shade of orange. And this was, you know, the eureka moment if you like. Because Bennett realized that what Duncker had tried to do was impossible. It wasn’t just a genetic effect, you also needed this environmental input. CURWOOD: What’s really fascinating here is that Hans Duncker was able to make this link between genetics and the environment back in the 1920s, but for some reason he couldn’t seem to apply it to his work with the search for the red canary. What happened? BIRKHEAD: It’s very interesting that when Duncker was interpreting how Reich had managed to create these nightingale canaries, he recognized that the canaries that Reich had bred had to learn the nightingale song. But what Reich had done was select birds that had the genes for the ability to learn. So Duncker recognized that both genes and the environment were crucial in creating Reich’s nightingale canaries. But he was, again, decades ahead of his time in this respect. And my sneaking suspicion is that because nobody ever patted him on the back for this and said “that’s brilliant,” he kind of flipped back into the genetic, deterministic thinking that was so prevalent at the time. And I’m convinced that had his work been recognized by more professional scientists, it might have changed the way he thought subsequently. CURWOOD: Tim Birkhead is a professor at the University of Sheffield in England and author of “A Brand New Bird: How Two Amateur Scientists Created the First Genetically Engineered Animal.” Thanks for speaking with me today. BIRKHEAD: Thank You. Living on Earth wants to hear from you!Living on Earth Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth! NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

|