Amazon Deforestation

Air Date: Week of February 25, 2005

Shortly after environmental activist Dorothy Stang was murdered in Brazil, the country's president Lula da Silva pledged to step up law enforcement to stop the violence. He has also agreed to create two large reserves in the area where the 74-year-old nun lived and worked. Host Steve Curwood talks to Outside Magazine contributing editor Patrick Symmes about Stang and the future of the Brazilian Amazon.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

When Amazon rainforest activist Chico Mendez was murdered outside of his home sixteen years ago, many thought his death would lead to reforms that would slow the destruction of the Amazon and end the corruption aiding its decline.

But even Chico Mendez, himself, was skeptical that his own death would change anything. This is actor Raul Julia playing the leader of the Brazilian rubber tappers union in the 1994 movie "The Burning Season."

FILM: If a messenger came down from heaven and guaranteed that my death would strengthen our cause, it might be worth it, yes. But it's not with big funerals that we're going to save the Amazon. I want to live.

CURWOOD: Recently, the funeral of another leading activist put hope into the minds of Brazilians and others around the world that the Amazon would benefit at last from the death of a martyr. This time the victim was seventy-four-year-old American nun Dorothy Stang who was shot six times at close range. Immediately after her slaying, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula Da Silva said he would establish more than 20 million acres of protected reserves in the forest regions where Sister Dorothy had lived and worked. He's also vowed to stop the violence against rural workers. Since Lula took office in 2003 Amazon deforestation has not only continued but it's been on the rise.

Joining us now is Patrick Symmes who is a contributing editor for Outside Magazine. Welcome, Patrick.

SYMMES: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Now, Patrick, several years ago you wrote a feature story called "Bloodwood" for Outside Magazine. It's about the illegal logging trade in Brazil. First, set the scene for me here. Now the government has pledged to set up a nine million acre reserve. What area are they talking about?

SYMMES: I've been in both of the reserves that make up that more than nine million acres. It's one of the main tributaries to the Amazon to the south, deeply wild region, full of meandering rivers, very subject to changes in the rainy season and the dry. The upperlands, the larger part of the reserve is home to a lot of Kaipo Indians and other groups, and logging has been encroaching in it bit by bit and people have been settling around the edges of it and logging companies are starting to...have been coming in for years now and stealing mahogany and other valuable trees off land that really doesn't belong to anybody. It's public land or Indian land. Some landowners claim it. So you have a lot of land conflicts over who gets the profits from abusing the Amazon and it's never the poor farmers who are the first ones who come in driven by a sense of hunger.

CURWOOD: Hmmm. How much is a mahogany tree worth?

SYMMES: By the side of the water in the upper Jingo watershed it's probably worth five to 20 dollars depending on how big it is, which would usually be paid for in sugar and gasoline to whichever farmer or poor person cut it down. By the time it gets to a sawmill, it's worth a couple thousand dollars. When it's cut into boards and shipped down to one of the great port cities like Manaos or Belém, it's worth probably a hundred thousand dollars. By the time it gets to a furniture showroom on Madison Avenue in New York, I've seen mahogany sideboards priced at 25 thousand dollars apiece. So that tree, in the end, could be worth a million dollars.

CURWOOD: And the guy who cuts it down gets maybe 20 bucks.

SYMMES: Sugar and gasoline.

CURWOOD: Now, how meaningful is this declaration by the Brazilian government to set these areas aside as a reserve?

SYMMES: It's very important as a watershed event in Brazil's relationship with the Amazon. The national project has always been to develop the Amazon, and Brazil has had a rise in its own environmental movement getting stronger; but the Amazon has always been out of bounds, a place that was lawless where politicians and businessmen set the agenda and there was impunity. Now that impunity, at least in theory, has been put on the table and is gonna be ended.

CURWOOD: To what extent is the government gonna back up this declaration with real enforcement? Boots on the ground with rifles?

SYMMES: Well, they sent a lot of soldiers into the Amazon immediately to try to make a show of force and a symbolic step, but that doesn't change things over the long run, just as these two reserves, as large as they are, in fact, they're just a tiny, tiny piece of the Amazon. The question is, there would need to be more reserves and more planned and are also being logged by companies coming in from overseas that looking for a quick return on some investment funds.

CURWOOD: This is nothing new, I mean, the Chico Mendez story from what? 1988 is, perhaps, the most famous of these.

SYMMES: That's right and look how little has really changed. What's quite frightening to me is, you hear headlines from time to time about the Amazon disappearing at a greater or lesser rate and what does this mean? The real story is that over time the rate has stayed just the same. Year after year, decade after decade. We have failed to stop or even really decrease deforestation. It just carries on forward. Nothing has changed since the days of Chico Mendez.

In theory, now, with a more democratic Brazil, a larger, popular environmental movement in the country, there is room for real change now in asserting that the Amazon must be governed. That logging must take place under a system with permits that are actually enforced and mean something.

CURWOOD: So, the Amazon has this history of activists trying to protect the forest being killed. Most recently Dorothy Stang, a nun. Tell me, what happened in her case? Where did this happen and what exactly did happen?

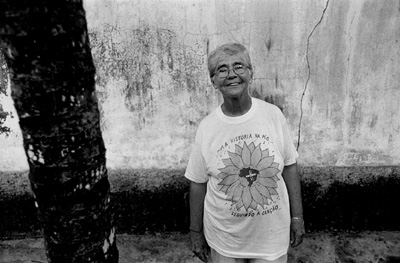

Dorothy Stang, an American nun, helped organize peasant farmers against illegal logging in the Brazilian Amazon. She was murdered on February 12, 2005. (Photo © Seamus Murphy)

CURWOOD: What was she like, you spent a fair amount of time with her?

SYMMES: She was a small very powerful woman. One of these people, she was sort of round, and not that imposing a figure. A genial, great smile, and sort of flashing eyes. Gray hair and just a great sense of humor and singing and you know, went around, she didn't wear a habit. She was wearing a t-shirt with an environmental sort of social struggle slogan on it. And she clearly had a sense that there was a tragedy taking place for Brazilians and for the people like her who were defending them and she was keenly aware that it was dangerous work. She made light of it, but you could see the pain in her eyes. She said oh, you know, she had gotten all these death threats and she said, "well, a dog that barks a lot, doesn't bite." But, eventually, they found a dog that would bite.

CURWOOD: The killing of a 73-year-old American nun who, by the way, I would take it could have been killed just about any time, clearly sends a message to the government that the killers don't believe that anyone is in charge, but them. Why do you think that they took this time, now, to do this?

SYMMES: The impunity had been spreading and growing. Previous promises to put an end to assassinations and the murder of land activists had been made and broken. And time after time, those who ordered assassinations, or insisted that a certain person be gotten rid of were left, you know, in their social clubs uninterrupted.

CURWOOD: Why do you think that now after the death of the nun, Sister Dorothy, that things will change?

SYMMES: I think Brazil has changed. Over the last, sort of, 25 or 30 years the big environmental movement in the first world has clamored over the Amazon without having any success at reducing deforestation. The difference now is that Brazil has a big environmental movement. The Brazilians are the ones marching and demanding protection of forests, the honoring of reserves, the rights of the indigenous. That's the only hope for change . I think.

CURWOOD: This does not sound like the easiest place in the world to live. And what is it like for the ordinary people who are there? I've heard stories that people working small areas of land will sometimes get a knock on the door and be told to clear out in a couple of hours because some large land-barren interest wants them out.

SYMMES: That's exactly right. Dorothy Stang was actually killed while walking to a meeting of peasant farmers who had been given an eviction threat by armed gunmen and been told "you have to be out of here in a couple of days." And they were organizing to defend themselves when she was killed. It's important to look away from the one crime of what happened to Dorothy Stang and remember that there are five hundred Brazilians who are living under death threats right now because they are activists in the Amazon.

CURWOOD: Patrick Symmes is a contributing editor at Outside Magazine. Thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

SYMMES: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Since we spoke to Patrick Symmes, yet another prominent Brazilian forest activist has been murdered. Dionisio Ribeiro, who was working to stop poaching and the illegal harvesting of palm trees, was gunned down at the Tingua nature reserve near Rio de Janeiro on February 22nd.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth