Bye-Bye Bayou

Air Date: Week of August 27, 2010

“This is our place in the universe.” Rosina Philippe can see her ancestors’ burial mounds from her kitchen window. But rising seas and sinking land could put them under water in a generation. (Photo: Jeff Young)

Katrina took their homes. BP’s spill took their jobs. And coastal erosion is taking the very land their ancestors called home for centuries. But the tiny, Native American community of Grand Bayou Village is determined to hang on. Host Jeff Young returns to Louisiana’s Plaquemines Parish to find out how the people of Grand Bayou he met in the wake of Hurricane Katrina are doing five years after the storm.

Transcript

YOUNG: This is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood, and we’re reporting from New Orleans. Five years have passed since the storms that flooded this city, reshaped the region and left indelible images in our minds. The long climb back from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita became even harder this April when BP’s doomed rig let loose a torrent of oil. Today we revisit some of the people and places we reported on in the wake of Katrina. We’ll hear who’s made it back and how the Gulf Coast might recover from the storms, the spill and the grinding, constant threat of coastal erosion.

Shrimping, oyster fishing and crabbing are more than jobs, they’re vital cultural links. Lingering concerns about oil contamination threaten the activities at the community’s heart. (Photo: Jeff Young)

YOUNG: About eight months after the storm I was reporting from Plaquemines Parish, that’s where the Mississippi Delta branches into a bird’s foot and the land melts into the Gulf. Towns like Venice, Port Sulphur and Empire were just beginning to rebuild. I got curious about the small gravel roads that climbed up and over the levee, and the people that lived beyond that protective wall of earth.

So I picked one at random and drove it to the end, through the treeless marsh to a boat landing. That’s where I met Raymond Reyes and Nicholas Bartholomew, both fishermen in their 60s and both still struggling to come back from Katrina.

REYES: This is grand bayou village they call this… all this around here is called Grand Bayou Village and we all live right here and uh, the only thing we do is trawl and catch oysters all we do all our lives, that’s all we do, you know. And we’re just hoping to get back in business.

BARTHOLEMEW: We didn’t make a lot of money but we made a livin,’ we made a livin’ that was the main thing. But Katrina came and took that away from us. And we can’t get no help from nobody.

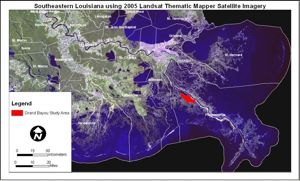

The Grand Bayou is represented in red in this map of Southern Louisiana. (University of New Orleans)

YOUNG: Mr. Bartholomew said he couldn’t get assistance to fix his heavily damaged boat. Mr. Reyes said most of the village’s 25 or so homes, on stilts above the water at the bayou’s edge, were still uninhabitable. Some people were living in FEMA trailers in nearby towns. They showed me where Mr. Reyes and some others were living: in the 10 by 12 foot cabins of their shrimp trawlers.

BARTHOLOMEW: They lived on there for six months during the storm. Six months they lived on this boat right here.

[WALKING INTO CABIN]

REYES: There was 4 or 5 of them.

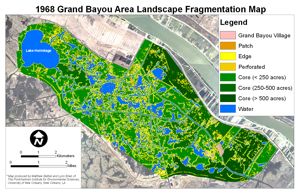

Grand Bayou in 1968. Water is represented in blue and land is green. (University of New Orleans)

BARTHOLOMEW: Four or five people living in this little cabin.

REYES: They had 2 bunks, the stove, a little bathroom, you know and fit five persons in here. Kinda crowded, you know.

[WALKING OUT OF CABIN, ALONG GANGPLANK ]

YOUNG: What do you think is going to happen here, is this community going to come back the way it was?

REYES: Oh I’m gonna tell you right now, them people here is die hard. They gonna come back. They gonna come back. Unless they find a better place to live they will come back but I don’t think they will find a better place than this, this is like heaven, you know. Everybody was together, it was a big old family, you know. So I don’t believe they gonna split up.

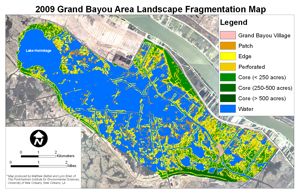

Grand Bayou in 2009. More than half the area is now covered with water. (University of New Orleans)

BARTHOLOMEW : It was like a big old family When they cook everybody eat. How many dinners they give in this here? People come and eat. Grand Bayou, the home of the free.

REYES: Don’t know when, but they will be back.

BARTHOLOMEW: Oh yeah definitely…they will be back. I might not see it cause I’m getting older but this place will bloom again.

YOUNG: That was Spring 2006. This summer I went back to that same boat landing to see if people had come back to Grand Bayou.

[BOAT ARRIVING AT LANDING]

YOUNG I recognized Raymond Reyes as soon as his boat pulled up. His hair might be a bit whiter now, but it’s a full head of hair that shines against his deeply tanned skin. He looks fit, and happy. In December he finally moved into his house after living on his trawler, the Uncle Norris, a lot longer than he had planned.

REYES: Four and a half years!

YOUNG: Wow!

REYES: Last time you saw us we was living on the uncle Norris, little bitty boat. Now we got a house, so we’re living in a house. We got everything we need, we got hot water, yeah we doing good. We happy. Way better than the boat! (laughs) Yep.

YOUNG: But shortly after Mr. Reyes got into a house he was out of work. The BP oil spill closed the shrimp and oyster beds. He’s been getting by with oil clean-up work.

REYES : I got my son here helping me working on the oil spill. So we doing good we happy now. Not what we want to do. But like I say we doing something we paying the bills. So, we’ll be alright, you know? We survived Katrina, this, we can survive this too. Like I said only thing to do is put our trust in the good lord and things will be fine.

YOUNG: Why was it so important to you to stay in Grand Bayou Village?

“We survived Katrina, we can survive this, too.” After 4 years living on his shrimp trawler, Raymond Reyes, 66, is finally back in a house. But the spill put him out of work. (Photo: Jeff Young)

REYES: Well I want to tell you something. My mom married my stepdad when I was two yrs old and I been here ever since. I’m 66 yrs old why would I change now? That’s my livelihood so I’m gonna stay here. Yep that’s all. We got the burial grounds right here, so why move? Everything is here you know? Everything we need is here- our livelihood is here and all my family is here so where can I go, you know?

YOUNG: Catching up with Mr. Reyes years after we first met, I finally started to understand his strong sense of place and community. made me realize just how special his community is. Grand Bayou is a native American village. They are the Atakapa-Ishak people. So when Mr. Reyes talks about the burial grounds- that’s not just a cemetery. It’s a burial mound. History for Grand Bayou stretches back centuries before the first western settlers arrived. And, for all that time, they have made a living from the bayou. Now there’s deep concern about whether that way-of-life can continue.

[BOAT STARTS]

YOUNG: Rosina Philippe meets me at the landing in a small boat. It’s the only way to get around in Grand Bayou Village, where Main Street is a waterway. Ms. Philippe is 54, she has a long black braid and a steady gaze. She’s Grand Bayou’s unofficial historian.

PHILIPPE: We’re in Grand Bayou right now. You can see some of the remnants of the homes.

YOUNG: Of the people who were displaced by Katrina, how many do you think have come back?

A house one Grand Bayou resident hopes to return to some day. Only 9 of 23 families have come back after Katrina. (Photo: Jeff Young)

PHILIPPE: Well, we only have managed to return nine families.

YOUNG: Out of how many that were here?

PHILIPPE: Out of 23

YOUNG: Nine out of 23.

PHILIPPE: Well, we’re still in recovery from Katrina with rebuilding the homes, returning people back to the village to reclaim their lives- it’s an ongoing process. And it seems that other things crop up to kind of bleed our energies and our attentions from that focus, like with the oil disaster in the Gulf.

YOUNG The bayou’s waters still teem with life, shrimp crabs and oysters.

PHILIPPE: Porpoises in the water!

YOUNG: Oh my gosh, there they are! Coming right at us.

PHILIPPE: Yes. They’re wonderful to watch.

YOUNG: When BP’s oil hit the nearby bay, it struck at the very core of Grand Bayou’s existence.

PHILIPPE: It’s one of the most serious impacts we’ve ever felt. We’ve been here in this region more than 1,000 years. We’re the first peoples in this region. We’ve had losses from natural hazards, some from human-induced impacts. But even at the worst of times in these other occurrences we were still able to feed ourselves, and to provide, at least, food for our families. Now that’s threatened. And we do not know the long-term impacts.

YOUNG: The backdrop to all this is that the land itself is disappearing. South Louisiana is eroding at an alarming rate—as much as a football field is lost every 40 minutes. It started with river levees cutting off the sediment-rich floodwaters that nourished the marsh. Natural subsidence of the soft delta soil accelerated. Then came the oil wells and miles of canals for pipelines and platforms that carved up the delicate wetlands.

PHILIPPE: They came in and manipulated nature and they took and took and took. They cut canals and allowed the saltwater to intrude, a lot of the trees and vegetation died off. You know we’ve seen all these things take place. And now that we know better, I do believe there are things that can be done. And there are some things being done, but it’s not aggressive enough. Because, you know, it’s almost you’re like giving a critical patient an aspirin when they have cancer.

[BOAT ENGINE FADES]

YOUNG: People from Grand Bayou are now helping coastal researchers better understand land loss in a partnership between science and traditional ecological knowledge.

BETHEL: Oh, it’s invaluable. I don’t know that we could have done this study without having that knowledge.

YOUNG: That’s Matt Bethel, at the University of New Orleans. Bethel’s project pairs up satellite and aerial images of the shrinking coast with the intimate knowledge that fishermen and trappers have of the local land.

BETHEL: They were able to fill in the blanks between image shots that we had and tell us, okay, what was going on here, what did you observe here while you were out fishing and trapping that would explain some of the things that we were seeing in the satellite images.

YOUNG: That level of detail could help guide restoration projects to save the marsh.

Bethel clicks through decades of aerial images of Grand Bayou. Narrow channels of oil pipeline canals widen into rivers over time. Small ponds become lakes and acres of land turn to open water. At this rate of loss, Grand Bayou could soon be swallowed by the Gulf of Mexico.

BETHEL: There are maps produced that show that this whole area will be gone by 2050. And, the Grand Bayou people have seen those maps…they know that. If they all move off and they scatter, they’ll tell you, they’re not the same people. They’re tied to the land, and without that, they don’t have anything.

[BOAT ENGINE]

YOUNG: The coastal erosion has national implications, as does the oil spill, as did Katrina. But the tiny community of Grand Bayou is on the frontline of all three; a microcosm of major challenges. Rosina Philippe says her people have learned to live in a changing environment. But now the changes come so quickly, it’s harder to adapt.

PHILIPPE: I’ve been asked this… well why do you put up with this? Why do you stay, why fight to return? I can only say that if you were here in Grand Bayou and you could know the peace and see what I see and you know, this is our place in the universe. This is where the creator set us down. In spite of all the impacts that have come at us both natural and human induced, we’re still here. This is where we belong.

[ENGINE DIES, OAR STIRS WATER]

YOUNG: She kills the engine and we sit and listen a moment to the marsh .

PHILIPPE: We have our sacred places still. We are a mounds culture, mounds builders. And they’re suffering from erosion and that’s the original site, you know, of our people here. Many, many, many generations.

YOUNG: What would it mean if burial mounds went underwater?

“This is our place in the universe.” Rosina Philippe can see her ancestors’ burial mounds from her kitchen window. But rising seas and sinking land could put them under water in a generation. (Photo: Jeff Young)

PHILIPPE: They have. There used to be twelve. We have three now. It’s a loss, I can’t even tell you the loss. I can’t even translate that into words, and to see the erosion and see the trees falling over because land has eroded away. I just wonder about the future generations – they’ll just have our history and our story, but they won’t have the place.

YOUNG: See photos of Grand Bayou and its people, and maps showing coastal land-loss at our website LOE dot org.

[MUSIC: Buckwheat Zydeco “Tee Nah Nah” from Zydeco Party (Rounder Records 2001)]

CURWOOD: In a moment, we’ll look at what the people of the Gulf Coast want their government to do to rebuild their lives and livelihood. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: Donald Harrison: “Indian Blues” from Indian Blues (Candid Records 1992)]

Links

Pontchartrain Institute for Environmental Sciences at U. of New Orleans

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth