Probing Dolphins’ Genetic Mysteries

Air Date: Week of February 6, 2015

A skull of a spinner dolphin killed in the tuna fishery housed in the NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center's Marine Mammal Life History Collection. Detailed measurements of hundreds of skulls were used to determine how many populations of dolphins were affected by the fishery. (Photo: Matthew S. Leslie)

Dolphins famously save people from drowning, but we still used to kill them by the millions, often as by-catch in tuna fishing nets. A huge collection of tissue from these inadvertently caught mammals is now helping unravel dolphins’ genetic secrets, as Matthew Leslie reports from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Dolphins are among the most beloved of ocean creatures. They are renowned in myth, and reality, for rescuing drowning humans, and leading boats safely through treacherous waters. Humans have also killed massive numbers of dolphins in the warm Pacific, because pods often associate with schools of tuna targeted by fishing boats. Ironically the huge numbers of animals killed before the Dolphin Protection Act came into effect in the US twenty-five years ago have yielded a unique genetic archive, and that’s the subject of this report in the series “One Species at a Time”. Matthew Leslie, a PhD candidate at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California has the story.

LESLIE: Sometimes an environmental problem is so difficult that it requires multiple

generations to solve. That’s certainly the case when it comes to the story of the two species I study: spotted dolphins, or Stenella attenuatta, and spinner dolphins, or Stenella longirostris.

I'll get to my work on these species in a minute, but first I need to give you some background.

A school of eastern spinner dolphins fleeing from research vessel. Spinner dolphins in most other parts of the world do not exhibit this response to vessels. The “flee” behavior is likely a response to the chase and encirclement methods of “dolphin set" tuna fishing in this region. (Photo: Robert L. Pitman of the National Marine Fisheries Service)

LESLIE: In the eastern Pacific, thousands of miles from land, spotted and spinner dolphins have a special bond with large tuna – they're almost always found together. Fishermen have known this for a long time, and they’ve come to rely on the dolphins they see at the surface to find schools of tuna below. For years, they used fishing poles to catch tuna. But all that changed in the 1960s with the advent of large plastic nets.

PERRIN: I went on a boat back in 1966 and saw the operation.

A pantropical spotted dolphin from the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. (Photo: Robert L. Pitman of the National Marine Fisheries Service)

LESLIE: This is my research advisor, Bill Perrin. He retired a few weeks ago, after working 46 years as a biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA. Back in the 60s, Perrin was a PhD student researching the fishery.

PERRIN: I was very impressed by it...tremendous stresses involved, great winches working in all a big industrial operation.

LESLIE: Nets a mile long could encircle entire schools of fish. Boats were harvesting more tuna than ever, but countless dolphins were paying the price.

PERRIN: The dolphins were trapped and many of them didn't make it out.

LESLIE: Perrin saw over a thousand dolphins die on a single fishing trip. He was deeply troubled. So he started a program to train over a hundred and fifty biologists to be observers on tuna boats.

The idea was to count how many dolphins were being killed, and collect as many samples as possible to understand the impacts on the dolphins.

An eastern spinner dolphin from the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. (Photo: Robert L. Pitman of the National Marine Fisheries Service)

LESLIE: In addition to the first estimates of how many dolphins were dying, the effort resulted in the best collection of dolphin tissue in the world, and it resides at NOAA's Southwest Fisheries Science Center, located right here on the Scripps campus. I call it the morgue. Susan Chivers is the curator, and she offered to show me around.

CHIVERS: It’s a very big space.

LESLIE: The room is about the size of a small gymnasium. It’s clean and bright with floor-to-ceiling shelves, each one packed with jars containing dolphin body parts.

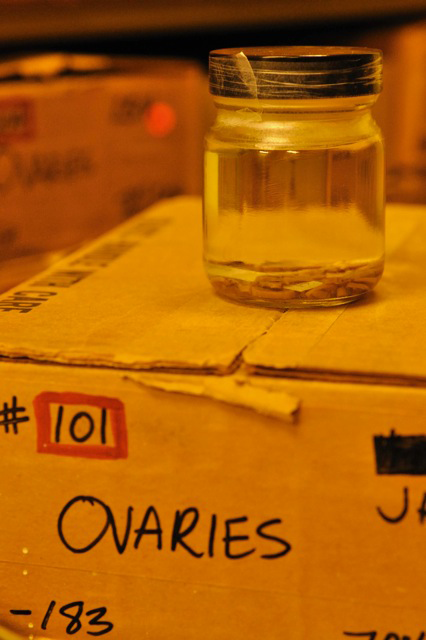

CHIVERS: Here we have a wall of gonads; banks and banks of ovaries.

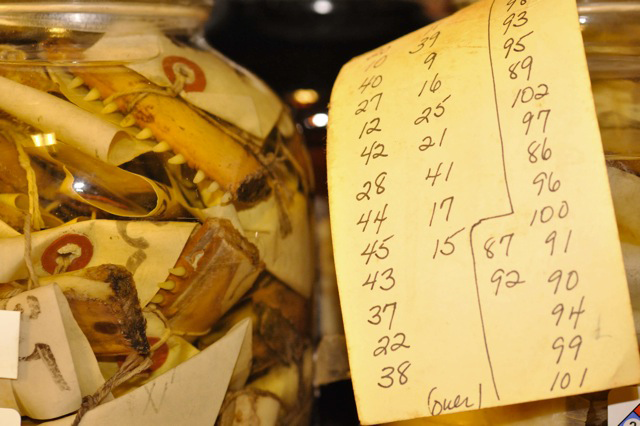

LESLIE: One shelf is packed with jars containing hundreds of jawbone fragments. Biologists used the teeth from these jaws to determine the age of the dolphins.

A jar containing the ovaries of a dolphin killed in the tuna fishery. We used the ovaries were used to determine whether the dolphin was sexually mature. This specimen comes from one of over 30,000 animals whose remains are housed in the NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center's Marine Mammal Life History Collection. (Photo: Matthew S. Leslie)

CHIVERS: It is moving for people to see - when you realize that the jaws of over 40,000 dolphins are here on these shelves. It does kind of bring it home to you how many dolphins were actually killed.

LESLIE: Over six million dolphins died as a result of this tuna fishery. And all those dead dolphins didn't go unnoticed.

PERRYMAN: The level of mortality became visible to the American public.

LESLIE: This is Wayne Perryman, a biologist at NOAA. Public outcry forced the fishermen to change their nets, and the way they haul them in, which allows the dolphins to escape. The kill is down from hundreds of thousands of animals a year to only about a thousand. You’d think that would be a good thing, but Perryman says the spotted and spinner dolphins still haven’t recovered.

PERRYMAN: We don't know why it’s taken so long. Maybe the fishery is having an effect we can’t measure. Maybe this is just the nature of populations.

LESLIE: Populations are just groups of individuals that don't really mix with one another, and to recover a species, we have to make sure that all the populations are recovering.

A jar containing jaw fragments from dolphins killed in the tuna fishery. We used these specimens to determine the age of each dolphin. They are housed in the NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center's Marine Mammal Life History Collection. (Photo: Matthew S. Leslie)

LESLIE: When Bill Perrin measured the dolphin skulls in the morgue, he found three populations of spinner dolphins and two populations of spotted dolphins. For the last 20 years conservationists have used these population definitions to manage the dolphins. But Perrin suspected early on that his approach was too coarse - that maybe there were even smaller groups, subpopulations, that need special protection.

That's where I come in. I'm using DNA that comes from the morgue to look for these

subpopulations. I assumed that because the skulls were different, the genes would be too. But when I looked at 14 different genes – I couldn't see the differences Perrin found. This doesn't mean they're not there, I think I'm just looking in the wrong place.

Now I'm scanning all the DNA of these dolphins - their entire genomes –hoping to find the subtle differences that reveal the smaller populations - so we can get the recovery plan right. My advisor Bill Perrin had no idea when he was collecting dead dolphins in the 60's, that one day we’d be able to peer inside their cells and read their DNA. And yet, the mission’s the same – saving the dolphins - and it makes this 40-year-old morgue as important as ever.

A skull from a spinner dolphin killed in the tuna fishery housed in the NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center's Marine Mammal Life History Collection. Detailed measurements of hundreds of skulls were used to determine how many populations of dolphins were affected by the fishery. (Photo: Matthew S. Leslie)

PERRIN: The tuna fisheries continue. We're not 100 percent sure that what they're doing is fully sustainability. We have data and specimens here that may help us answer that question. It’s a gold mine.

LESLIE: I’m honored to be following in Perrin's footsteps, to solve a problem that my generation inherited from his and applying the latest tools in science to specimens collected well before I was born.

CURWOOD: That’s Matthew Leslie, a PhD candidate at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. His story is part of the series, One Species at a Time, produced by Ari Daniel and Atlantic Public Media in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, with support from the National Science Foundation.

Links

More on the dolphin problem in tuna fisheries

Matthew S. Leslie is a PhD candidate at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Matthew S. Leslie’s personal page

Study from Scripps on how fisheries impact dolphin populations

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth