Defending Darwin

Air Date: Week of March 27, 2015

"Evolution" 1992, oil on wood panel, 96 x 288" (Image: courtesy Alexis Rockman and Sperone Westwater Gallery)

The University of Kentucky, is located in the heart of the Bible Belt, a region with many Fundamentalist Christians who are skeptical of the theory of evolution. Today, Jim Krupa is a biology professor at UK who has taught evolution to thousands of students, some of whom believe that the idea of evolution, as posited by Charles Darwin, is fraudulent and the Earth and its creatures are only about 6000 years old. Prof. Krupa tells host Steve Curwood that despite opposition from some students, he’s following in the footsteps of UK educators who have defended academic freedom and scientific fact.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. A number of fundamentalist Christians believe that the bible is the word of God and trumps all human knowledge, including the scientific evidence that life has been evolving on Earth for millions of years. These creationists believe God created the Earth and its inhabitants over the course of just seven days, roughly 6,000 years ago. So of all the difficult jobs one might imagine, teaching evolution in America’s bible belt must rank near the top. But there are dedicated educators who choose this thorny path, and one of them, a biology professor at the University of Kentucky, wrote his personal story in Orion magazine. It was so engaging, I went to visit him.

KRUPA: Hello, my name is Jim Krupa, I'm a professor here at the University of Kentucky. I teach evolution and vertebrate biology. We're outside of my laboratory in this glorious windowless building where all biologists are kept.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] We'll I'd like to see inside.

KRUPA: Let's go on in.

[KEY TURNING IN LOCK]

CURWOOD: Jim’s lab looks like a cabinet of wonders or a natural history museum, with a huge stuffed sailfish behind his crowded desk and skulls all along the walls.

KRUPA: Well, some of these skulls are really fascinating - there’s a gorilla up there that's been at this university since 1870. It's so fragile I don't even touch it. There is a leopard skull that apparently died at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis. I think it's interesting because Teddy Roosevelt was at that fair. There's a chance he may have looked at that animal. And then an old wolf's skull from Alaska, Kodiak grizzly from Alaska, all of these have been here for over 100 years. Any kind of road kill that I might happen upon I will clean up and use for teaching, so all sorts of good things here, hundreds and hundreds of skulls.

CURWOOD: But not every exhibit in Jim’s lab is long dead. We walk over to a series of tanks filled with snakes.

KRUPA: The ones over there the green ones are Japanese rat snakes. I've had them since they hatched and they don't like me very much. This one is a very pretty snake. It's called a milk snake. 'Hi, how you doing.' So this is a gorgeous animal.

CURWOOD: Oh, wow, look at that.

KRUPA: They normally don't bite.

CURWOOD: It's red...it's actually sort of a vivid pink almost, and black and white band.

KRUPA: Reddish orange so it's a mimic of the deadly coral snake. So the old saying is, red on black, friend of Jack, red on yellow, kill a fellow. So, if it's red on yellow, it's a coral snake in North America, but I don't have any of those, so this basically a mimic of a poisonous snake.

CURWOOD: There's one next to it from South Africa.

KRUPA: Yeah, all these African Egg-eating Snakes from South Africa. I like them when I don't see them that means they're happy and healthy and fed. He likes to act tough...there you go...so he's now...

CURWOOD: I want to see what he's going to say.

[SNAKE HISSES]

CURWOOD: Whoa!

KRUPA: It has almost no teeth so it's pretty much defenseless, so it basically mimics a venomous snake from Africa, the Rhombic Viper I think it is. So yes, if you can't be tough, look tough, act tough and keep people away.

CURWOOD: Jim’s academic research, though is not on animals – but on plants that eat animals.

KRUPA: Alright so here we have Venus fly traps getting ready to go into flower. They've been dormant, now they're starting to bounce back. These are some more carnivorous plants. These are pitcher plants from Australia here and here.

CURWOOD: So they're meat eaters but they're lovely...

KRUPA: Insect capturing. Oh, they're very beautiful. They were Darwin's favorite plants. He wrote an entire book on carnivorous plants. Yeah, there are 600 species all around the world.

CURWOOD: I suppose it's fair. If we eat plants, they should get a crack at eating animals.

KRUPA: Yeah, and they need it. Insects fall in and they get the nitrogen and the phosphorous and they don't have to get it from the soils so they can grow in nutrient poor soil because they get their nutrients from elsewhere. So, it’s a very interesting adaptation.

Jim Krupa and Steve Curwood holding a Milk Snake (Photo: Anastasia Curwood)

CURWOOD: As well as studying pitcher plants, for the past 20 years Jim has spent much of his time teaching an introductory biology course, including evolution. Some fundamentalist students challenge him, but there’s a long tradition at the University of Kentucky of scholars who defended the great evolutionary theoretician Charles Darwin. In fact one of UK’s most famous alumni is John Scopes, who was put on trial in neighboring Tennessee 90 years ago for teaching evolution. The so-called Scopes Monkey Trial was the first major trial broadcast on the radio and the epic battle between its two famous lawyers, presidential contender William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow, riveted audiences across America. But as Jim points out, the fight for academic freedom had already been narrowly won in Kentucky.

KRUPA: 1921, 1922, Kentucky was the first state where there was a movement to pass an anti-evolution bill where one of the forms of the bill had it such where there could be a $5,000 fine for teaching evolution and up to a year in prison. So it was a very hard-fought battle to stop this anti-evolution movement from happening, hence the University of Kentucky's Frank McVey, one of the great presidents, was the one who really stood up and fought it. He spoke to the politicians in Frankfort, Kentucky, he wrote letters. On, as it turned out, Darwin's birthday, which is Abraham Lincoln's birthday, so the 12th of February, 1922, he wrote a letter to the people of Kentucky explaining this was an attack on the university, an attack on academic freedom, an attack on one's religious beliefs and that this law would do incredible damage to the university and the state. And as a result, a few weeks later, the final vote came down to a 42-41 vote defeating the bill, the law, so off the attention went to Tennessee. So it was really a marvelous thing because he put his job on the line.

CURWOOD: And during this, there is a student at the University of Kentucky named John Scopes. What happened with him?

KRUPA: Yes, isn't it amazing. All this is going on. John Scopes is watching this unfold. His three favorite teachers - Professor Miller, Professor Turell Professor Funkhauser - were heavily engaged in the battle helping Frank McVey. William Jennings Bryan was in town giving talks on this, he was attending the talks. From here in 1924, Scopes took a teaching position in Dayton, Tennessee, teaching chemistry and the football coach and he did a little substitute teaching in biology. And so, he basically offered himself up to be the person that was charged for teaching evolution in Dayton, Tennessee, and he stepped into history, in part, because he was inspired by his teachers here at the University of Kentucky and President McVey.

CURWOOD: Jim, so, what did you think when you were offered a position to teach here at the University of Kentucky?

KRUPA: Oh my God, I don't want to teach hundreds and hundreds of students in giant classrooms. I want to teach a little class of 25 students where and hold my skulls and have them hold snakes. It was scary because an auditorium full of students, that's a daunting teaching environment and I wasn't sure I could do it so I was very apprehensive about taking the job at first.

CURWOOD: And what about the place's reputation. I mean, this part of the country, a lot of folks who are still very upset about the notion of evolution?

KRUPA: Well I got my PhD at the University of Oklahoma and it isn't any different there, so I was used to this environment by the time I got here, but you know that didn't matter because evolution is the foundation of our science so I don't care what the general public thinks about it, this is what...it defines biology...this is what I'm going to teach.

CURWOOD: Now, you write that EO Wilson inspired you to take this job. What did he say that got you to say, "Yeah I can do this."

Jim Krupa’s lab is filled with animal skulls from all over the world. (Photo: Anastasia Curwood)

KRUPA: Well, he didn't say anything to me personally, but it was right around the time where his autobiography came out, and the title is "Naturalist" which I love being one, but he was being interviewed on NPR and Bob Edwards asked him why he was still teaching introductory biology at Harvard when he is one of the most famous biologists, but what he said to Bob was it's the most important course that he could teach. Many of nation's leaders, being at Harvard would be taking that class, and so this is the last shot he had at convincing them that science and biology is something wonderful. So, he had to do it because he knew it was a very important course, and that's what kept me here, because I was still thinking about leaving but sometimes you have to do something for a greater good. And it turned out I have a knack for teaching big classes so it was kind of fun.

CURWOOD: So, what was it like when you first started? I mean, how much push back did you get from some of the students in your class?

KRUPA: Well, not a lot, face to face. Most of it, at the end of the semester when we get the written comments on our teaching evaluations, that's what shocked me, and I have pages and pages of written comments about, "You have no right to teach us evolution. It's not science. It's religion. It's atheism. You shouldn't be teaching it." Da da da da. But again, that's a small percent of the students, but a vocal minority can make a lot of noise.

CURWOOD: Yeah, tell me about some of those tense moments with what you call the vocal minority.

KRUPA: I had the one student who shouted from the back of the auditorium that Darwin denounced evolution on his deathbed and therefore I shouldn't be teaching it. Of course, that's a lie. The creationist who made that up admitted it, and that was a strange thing to have a student shout out and then walk out. And I've had that not quite a dozen times over 20 years so it throws you for a bit of a loop every time.

CURWOOD: What do you say to folks that evolution is a theory and therefore not a fact?

KRUPA: Well, I have to explain to them what theory is, and I'm kind of a grumpy old man in many ways. I get upset every time I hear the word "theory" being used incorrectly, which is on a daily basis, but I explain to them that a theory is this broad comprehensive of some aspect of nature that generates testable and falsifiable predictions. It's not a hunch, it's not a notion as people think, so I try to make the point very clearly of what theory is, and I do explain that as one of the most powerful tools that science has. It's what we base what we do on. And then I explain a fact versus hypothesis, but I make it very clear what a theory is, I make it very clear what a fact is, and that evolution is both. And of course, I'll have people say, "No. It can't be. It has to be one over the other." And my response is always, "Well. We have something called cell theory and yet it's a fact we are made of cells. We know gravity exists, but it's called gravitational theory. We know pathogens are what cause disease but it's still germ theory." So, I go at it to a point where it's ridiculous. But you have to keep making the point over and over and over.

CURWOOD: To what extent did you address religion in those introductory classes?

KRUPA: Well, in human ecology, I don't touch it at all, but in the non-majors general biology I really didn't touch it until the very end. But in the last lecture I give them what I call the social resistance to evolution lecture and that's where I hit it head on. That's where I explain all the Christian denominations that accept evolution; I give them plenty of examples of evangelical Christians who defend evolution, so Francis Collins, the director of NIH, evangelical Christian. My job is to explain to them that when somebody, their parents, their ministers, their friends tell them that it's either evolution or God, you can't have both, I point out that's an error and I give them as many examples of Christians of various denominations who are also evolutionary biologists and say, "So here you go. This line is blurred." And so that's the last lecture. That can be the lecture that gets me the most stressed and worked up ahead of time because this is where I'm going to have some people that are upset that I'm even saying this. So I had to think about this for years...well, maybe a year whether or not I should do this lecture and I actually talked to my chair at the time and said, "So, there's not a problem with talking about the social resistance to evolution and the religion and science clash?" And basically, he says, "It's academic freedom. You need to hit it head on." And so, I've been doing it ever since.

CURWOOD: How do people react when you teach about climate change, climate disruption?

KRUPA: Same thing. When I got out of the non-majors classes it seemed that they were being less upset about evolution but more upset about this climate change stuff. And the statistics are a larger percent of Americans don't accept climate change so a lot of push back, same kind of push back, teaching evaluations are loaded with comments about I shouldn't be teaching it, it's not true, there's no evidence, stick to the facts and on and on. It's a very frustrating thing to see, and that's not connected to religious beliefs, that's rejection of science. So, yeah, it's very, very frustrating. So I got beaten up very thoroughly teaching those two topics.

CURWOOD: So what do we need to do as a country, as a society to foster better acceptance of science?

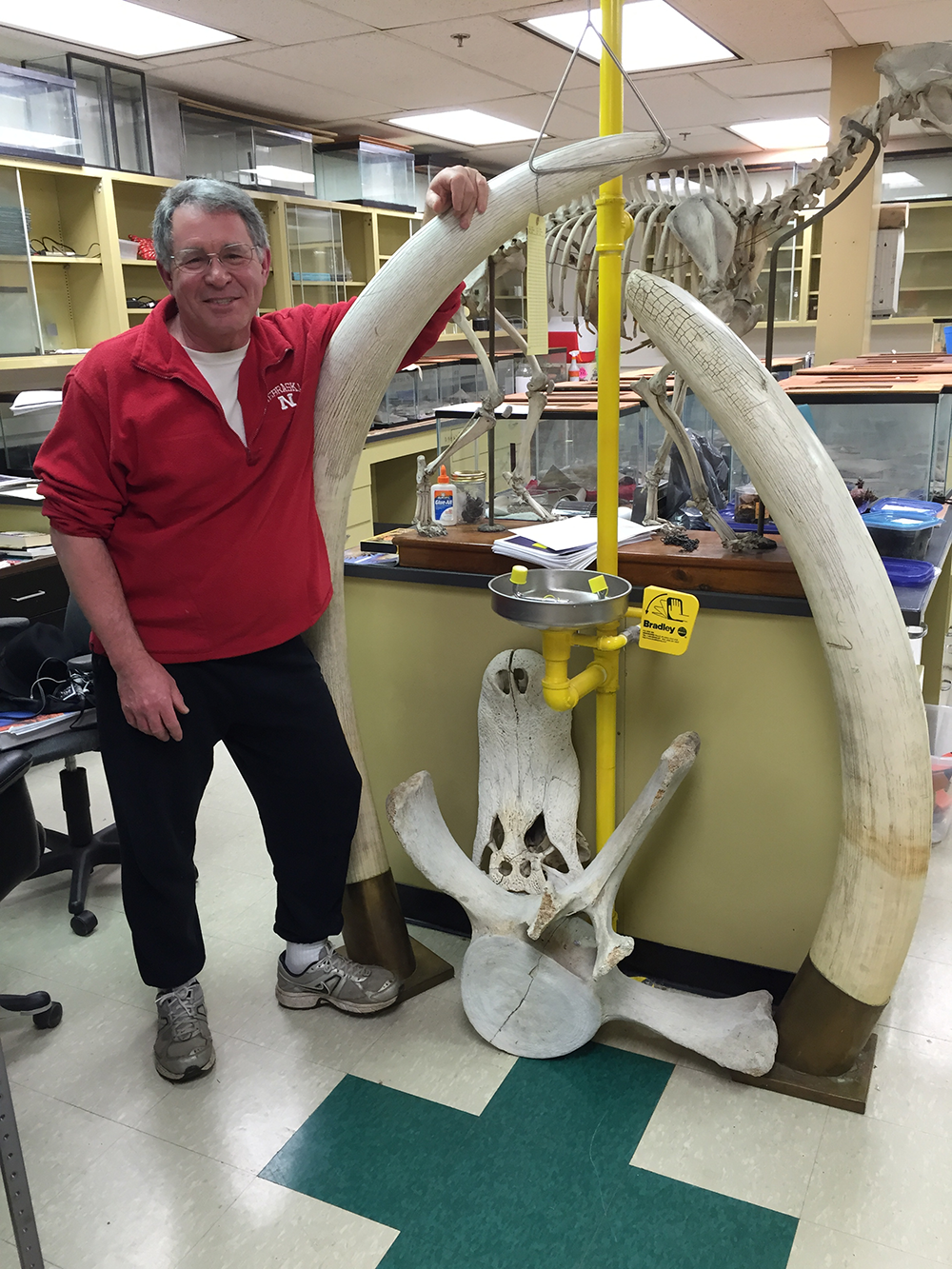

Jim Krupa with a pair of ancient elephant tusks (Photo: Anastasia Curwood)

KRUPA: Well we need better science education. I think we need to help all the teachers by giving them a stronger foundation of evolutionary biology, climate change, and help give them the tools to deal with the parents that are going to reject it. So we have to help the teachers. We have to train future teachers better so basically we in academics, the university level academics are the ones that are failing here, but things need to be changed so, it's not just paying teachers more. We need to help them be trained better. Any teacher that will be teaching high school biology, we really should have them take an evolution course. The National Center for Science Education is there to help any teacher that needs the help, and they're doing workshops. They put a lot of effort into this so we've got to provide the information for the teachers. We've got to help them, because, well, they're teaching their guts out. So how do we make this nation more accepting of science? The anti-vaccination movement, how do we deal with that? The anti-climate attitude, how do we deal with that? It's a frustrating thing. So if someone has the answer, we need to hear it.

CURWOOD: You end the piece you wrote in Orion Magazine with the story of a run-in with a former student who, well, wasn't very accepting of your lessons on evolution but then went on to become a physician. Tell us about it please.

KRUPA: This is a great story. I taught a freshman seminar called Evolutionary Medicine. He took the class, evangelical, believed in the literal truth of the Bible and the Genesis, and he really struggled with this evolutionary medicine stuff, but he stuck with the class. And we had several encounters over the years where I saw him, I think it was probably, oh, it's been several years now, I was out on the road bicycling. And I was at about my 20th mile; he was probably on his 50th mile. And being much younger he shot by me and he came back and he recognized me. And we had a long talk while we're bicycling and he told me that he after the class went and listened to a number of Creationists and was really pretty embarrassed and appalled that fellow evangelical Christians were basically lying and he recognized they were lying. And he said, I realize now, as you said, I can have my religious beliefs and accept evolution. And so he thanked me and off he went.

And so, I had not seen him for a while and actually about a year ago I was in the hospital, I got hit with pneumonia where I almost died a couple of times and so I'm laying on this bed in emergency here at the University of Kentucky and here he came in as a resident and we had a great talk and he hoped that I was well and that he was just finishing up and he was I think joining Doctors without Borders and then I saw him for the last time this summer. I walked by him on the way to the hospital and he was thrilled to see that I was doing OK and the first thing he said with a huge smile on his face was, "You turned my world upside down. You blurred the lines between black and white." And then he thanked me. And it was just pretty marvelous to see that here is at least one student out of my 24,000 students that realized that he could have his faith and accept evolution and it was OK. And that made it worthwhile, it was like I might as well hang it up and retire now. I have a victory.

CURWOOD: Jim Krupa is a Biology Professor at the University of Kentucky. His article in Orion is called "Defending Darwin". Thanks for taking the time with me today.

KRUPA: You bet. Thanks. This was great fun!

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth