Liter of Light

Air Date: Week of April 3, 2015

Illac Diaz is the founder of MyShelter Foundation, which seeks to provide affordable and sustainable building solutions for low-income communities. (Photo: courtesy of Liter of Light USA)

Countries in the developing world often have limited access to affordable electricity, and extreme weather linked to climate change makes the problem worse. Now, disaster rehab specialist and social entrepreneur Illac Diaz’s “Liter of Light” project has created a clever, affordable solution, recycling discarded plastic water bottles into solar light bulbs. He showed his invention to Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer and explained how US school children are building the lights to help transform lives for people in energy-poor regions.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Every so often, we come across an ingenious innovation that we feel we must report on – and we’ve just heard about one called Liter of Light. Now, it’s not exactly our discovery – indeed, this neat invention won the 2015 Zayed Future Energy Prize – an award given by the United Arab Emirates - and its inventor came by to show Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer what it is and how it works.

DIAZ: My name is Illac Diaz, and I’m the Executive Director of Liter of Light Global Movement to open source technologies for solar. Basically we wanted to create the cheapest solar light in the world.

PALMER: And Diaz may just have done that. This light had to be cheap, widely available and local people had to be able to assemble it. The key is empty plastic water bottles.

DIAZ: And one of the things that's most available anywhere in the world was a discarded plastic bottle.

PALMER: So these water bottles that we see ubiquitously everywhere? That's what we’re talking about?

PALMER: I’m talking exactly that, and if you think about it there’s not really any recycling in developing countries, so that bottle is going to last for 100 years, and so we were thinking what if we could make the biggest problem the biggest solution?

PALMER: Illac Diaz is a specialist in disaster rehabilitation – helping developing countries recover from floods and storms, and he had plenty of opportunity in his home country, the Philippines – which suffered the devastation of Typhoon Haiyan in 2013.

An installed Liter of Light kit glows in an otherwise dark home. (Photo: courtesy of Liter of Light USA)

DIAZ: Since 2013 is when the storms are becoming so powerful that instead of slowing down before hitting the archipelago, they actually go straight through, so Haiyan was really an indicator of things to come, where climate change is on us in a very strong way and we’re in front lines.

PALMER: That typhoon flattened over 14 million houses. Aid arrived within 72 hours and included bottles of water that piled up empty behind refugee centers. So Diaz set the many refugees to filling up those plastic bottles with mud, drying them in the sun to use for bricks to build schools. But those mud filled bottles made the schools dark.

DIAZ: One of the big problems with that was really you could not get any flat glass so we’d fill bottles with water and so for bricks fill it with mud, stuck it on top of each other, then in between every one meter fill one with water and this would allow a really beautiful light to envelop the whole school.

PALMER: So those were the first water bottles to bring light inside buildings, but Diaz saw he could use the same technique to light the inside of shacks in cities like Manila where houses are so jam packed together, it’s dark inside. It’s another simple idea – a bottle poking up through the roof to let in the sunlight that could create a business.

Founder Illac Diaz collects plastic bottles that will later be installed in roofs in energy-poor countries and regions hit by weather disasters. (Photo: courtesy of Liter of Light USA)

DIAZ: And we would have somebody who would collect bottles. He would buy a little piece of tin and glue and stick it. When he installs it, he starts saving that family or that household $8 to $10 worth of electricity a month. And so women would be able to do household chores, cook, clean the house, without having to bring around a candle, and this of course would be one of the main causes of fires. And so, the next household says, "How come I have to clean in the dark with a little candlelight when my neighbor just sticks a plastic bottle in the roof?"

PALMER: So if I'm looking at it, I’d be looking at this corrugated iron roof, and I'd see a third of the bottle sticking up, getting the sunlight, and this is just a bottle – there's no wires, no electricity, no battery?

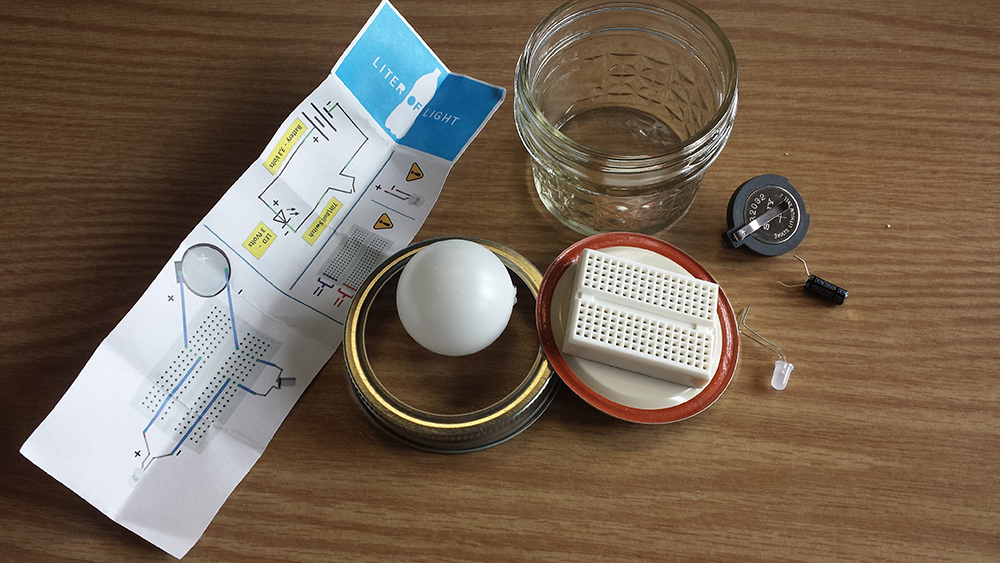

Liter of Light’s kit can generate light energy, is compact and costs about $1.50 US. (Photo: Lauren Hinkel)

DIAZ: No, so we would have a metal sheet like a 12 by 12 metal sheet and we would have a bottle in the middle, and we would have people that we would teach how to do it properly, and what kind of glue to make – of course, all of it local – and in a year we would train about 50 of them. Now, imagine this: each one of them would install about 11,000 lights in about two years.

PALMER: Each of these bottles costs just a dollar fifty to install. Liter of Light made a video of a slum area in the Philippines, Sitio Maligaya, in Central Luzon province where 643 water bottle lights have been stuck in the roofs — and an installer called Solar Demi explains what he does.

[SOUND OF FILM AUDIO, MAN TALKING IN TAGALOG LANGUAGE]

MAN: I’ve brightened up their dark homes. You punch a hole in a piece of metal roofing, apply some sealant, then fill it with filtered water, add some bleach and install it on the roof. Make sure it’s sealed, so the roof won’t leak. It’s that simple.

PALMER: This simple invention has transformed the lives of these slum dwellers, but Diaz says that’s not the half of it. Next came the nighttime solution. It makes use of latest technology – the LED – just a tenth of the power of a standard light bulb – and can also be stuck inside a plastic bottle.

One Liter of Light kit includes a small ping pong ball, an LED light, a battery and a solar panel. (Photo: Lauren Hinkel)

DIAZ: You would open the top, then stick in an LED light inside. So you’d see a bottle with a small one watt solar panel – and with an LED sticking inside – and a switch so even with at one watt at night it would be bright enough for ambient light.

PALMER: Not bright enough to read by, but bright enough so you don’t trip over family members in the house at night. Women were excited by the new lights, and Diaz trained them to assemble the simple circuits that make them work. But many of the women also run small stores and there was a problem with street crime. So they thought brighter lights might make a difference. And the next idea was streetlights, powered by a four watt solar panel, or a motorcycle battery.

Diaz and children hold constructed light kits. (Photo: courtesy of Liter of Light USA)

DIAZ: And so what we did was we started same thing, but instead of just putting it in circuits for house, we would use the same on and off switch to put in PVC pipes, and then we would have this soldering machine by the sun where we would have a battery and women would be able to solder street lights. And so, PVCs are all over the place, quick to find, you can put them on a bamboo pole, and the plastic bottle, we would put the LEDs inside, and we would attach them not along the streets but along small stores of women. Each woman would have a store, and we would put the lights right in front, you know if it breaks in three years, she would have a little bit of money from us to repair. So that became our business model.

PALMER: Now, you've brought one of them along with you. So, can we have a look at it?

DIAZ: I can bring it over.

PALMER: OK. So to describe it. There's the plastic bottle on the end of one piece of PVC pipe, which is at right angles to a vertical piece and on top of the vertical piece is the solar panels.

DIAZ: And then of course the circuit of turning on and off, there's a box and a battery, this on and off switch. So this one is built by the women. It's just an on and off switch so that you don’t have to turn the light on and off every evening, and then you would have a battery. Sometimes if we're really desperate we use a motorcycle battery, which would probably last for a couple of years. And so we would use PVC. And now, these kinds of small solar panels are very much used in my country and in other countries. So all of this is simply something we can get our hands on immediately. And there you have your four watts of streetlight, so this is four watts. And if you look at the end, all of this is soldered together by hand on a simple aluminum strip, and there you have your streetlight.

Illac Diaz shows former Senator and Secretary of State John Kerry how a plastic bottle can be recycled to provide light. (Photo: courtesy of Liter of Light USA)

PALMER: Each of these streetlights costs $50 to $70 dollars to build, and where they’ve been installed, the crime rate has been cut by 70 percent. Just this year, Diaz says, they’ve installed over 6,000 of these lights worldwide – in Pakistan, in Colombia, in Kenya, in Bangladesh. Liter of Light USA has just launched, appropriately enough at the Thomas Edison museum, and Diaz says they’re teaching children in New Jersey to make the circuits to send to developing countries. That way children in the US they can learn about energy poverty - and have a useful skill for the next time a Hurricane Sandy puts all of us in the dark.

DIAZ: The next generation is to start moving really in a technology of the people, preparing children, preparing people to know how to build these kinds of things, the do-it-yourself streetlights. That’s what Liter of Light is, to go into schools where children and parents find it relevant for the children to be able to know how to build their own streetlights and house lights. We've had experiences for those that we've taught, when they do travel they take our kits with them and then they see somebody who lives in darkness. And it’s something that the children they can build it and donate it – and so they become our missionaries, they become our ambassadors of light. And so this is the way we feel the revolution of solving energy poverty is not by asking people to buy our products, but it's only by multiplying ourselves, by sharing the technology, by getting more people involved that we will be able to solve this.

PALMER: That’s Illac Diaz of Liter of Light. And, Steve, he gave me one of the LED kits the school kids are building here.

CURWOOD: Looks like a tiny mason jar. Let me open it up.

[JAR LID UNSCREWS]

PALMER: Yes, and inside there’s a little circuit board, an LED light, a ping pong ball that becomes the bulb...

[SOUND OF BOUNCING PING PONG BALL]

PALMER: ...and instructions for how to build your very own little light.

CURWOOD: That’s so cool, Helen. Living on Earth's Helen Palmer. And if you want to build your own plastic bottle light there are instructions and much more at our website, LOE.org.

Links

PBS Newshour Profile: Illac Diaz Brings Clean, Cheap Light into Filipino Homes

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth