Coal Rising in the West

Air Date: Week of May 29, 2015

A coal haul truck on the Eagle Butte Mine in Gillette, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

Coal no longer provides the majority of US electricity, but strip mining coal is still big business in Montana and Wyoming, where massive machines gouge it out around the clock. Clay Scott of Mountain West Voices explores how western coal generates wealth, jobs and export dollars, but creates some problems for western ranchers.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Last week, we looked at the legacy of coal in Appalachia: how mining employed and fed generations, shaped and helped destroy the landscape. And we looked ahead to ways one-time miners and their families were trying to forge a future in the face of declining domestic consumption of coal. But in Montana and Wyoming, coal is still mined in huge quantities. It’s plentiful there, easier to access, and cleaner burning than West Virginia and Kentucky coal. Western coal is the focus of the last part of this team report from Mountain West Voices, High Plains News, West Virginia Public Radio and the Allegheny Front. Here’s Clay Scott.

[SOUND OF COAL TRAIN]

SCOTT: It’s a familiar sight in much of the country – long, slow trains of 100…120 cars or more. Each piled high with dull, black coal. 70% of all American coal moves by rail, often a thousand miles or more to its destination. Most of the time, that destination is a power plant. But some coal heads to ports for shipping - to meet demand in Asia, and perhaps, more surprising, Europe. The biggest coal ports are New Orleans, Mobile and Houston-Galveston on the Gulf Coast, along with Norfolk and Baltimore in the East.

[SOUND OF COAL TRANSPORT SHIP]

SCOTT: Several proposed coal export docks, especially on the West Coast, met intense public opposition, and they were forced to fold. Many opponents are concerned about carbon emissions into the atmosphere anywhere, and they say: “Leave it in the ground.” Others have a different worry - the coal dust that can blow off uncovered rail cars – up to five hundred pounds per car per five hundred miles. These nixed export terminals would have taken their coal from the Powder River Basin – the region straddling Wyoming and Montana that has long since eclipsed Appalachia as the center of American coal production.

The coal face of the Eagle Butte Mine near Gillette, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

Even with a slight recent dip in production, Wyoming alone still produces 40% of the nation’s coal – far more than any other state. And although coal in the Powder River Basin shares a crowded field with many other resources being extracted – oil, gas, uranium – it is the energy-rich black rock that has left the biggest stamp on the people and landscape of this region.

Traveling south of Gillette, Wyoming, through an arid and austere country once home to herds of bison, you pass coal mine after coal mine, for 70 uninterrupted miles, carving deep troughs into the prairie. Seen from a distance, the immensity of the mining activity is striking. But descend into one of these open pit mines for the first time, and it’s hard not to be overwhelmed by the sheer scale of things.

[SOUND OF EXPLOSION]

SCOTT: Blasting teams set explosive charges to loosen the steep sides of what look like gigantic sunken amphitheaters. Colossal digging machines called coal shovels load hundreds of tons at a time into haul trucks three stories high. Huge bulldozers rip away layers of dirt to get at rich coal seams, and clouds of brown and black dust darken the air. Endless trains of railroad cars snake through the mine to be piled high with coal. The scene is at once intimidating, surreal, and impressively efficient.

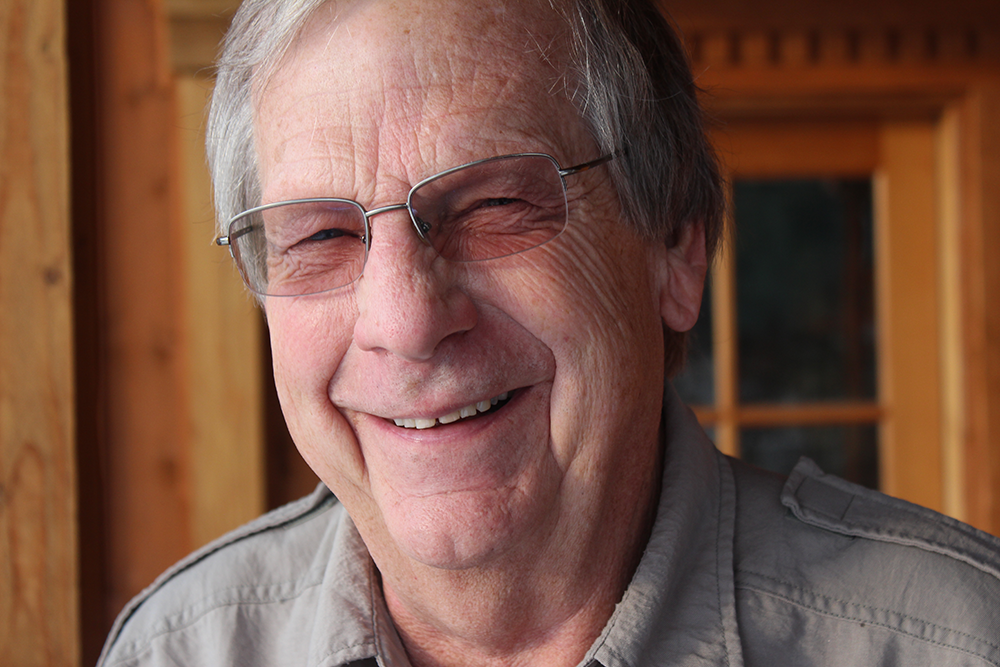

Bill Ritchie is a retired coal mine manager. (Photo: Clay Scott)

[SOUND OF CLIMBING LADDER]

SCOTT: At the Eagle Butte Mine, near Gillette, J. D. Dietsche showed me the coal shovel he’s operated for Alpha Coal for a decade, seven days on, seven days off. On a frigid day, my hands stick to the metal rungs as we climb into the $50 million dollar machine.

DIETSCHE: You drive your truck to the dirt shovel, get a load of dirt, take it to the dump, come back and do it again and again and again and again, [laughs] for 12 ½ hours. Minus your half hour lunch break. It is very, very repetitious.

SCOTT: It is repetitious work, often dangerous, and the hours are long. But coal is an important part of the economy of this sparsely populated state, and the 7,000 or so jobs it provides are highly sought after. Miners like Carrie Sieh, who’s worked in coal for 30 years, have raised their families with their earnings. But it’s more than just a paycheck.

SIEH: Because we are willing to go out, and run that equipment, and mine the coal, and bring it out of the earth, and we work holidays, 24/7, through snow, through rain, through all kinds of weather, then everybody else has the luxuries of electricity, and running water.

Miner Carrie Sieh in Gilette, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: The coal that’s mined each year in the Powder River Basin – 400 million tons of it - supplies power to millions of people. It’s lower in polluting sulfur than eastern coal, and closer to the surface. But while you might not have to blow the tops off mountains to get at the seams, coal mining here has still impacted the land, and the people who depend on it, in profound and far-reaching ways.

[SOUND OF MAGPIES]

TURNER: From our perspective in here, it really seems that most of the time, we’re the only ones that don’t have the ranch for sale and hoping to sell it to the coal company.

SCOTT: That’s L. J. Turner. His family has ranched in the southern end of the Powder River Basin since 1916.

TURNER: This is home. It’s been home for all of our lives. It’s uh…it’s going to continue to be so.

SCOTT: We’re standing on a low ridge at the eastern edge of L. J.’s ranch, looking out at the North Antelope – Rochelle coalmine. The mine sprawls for miles over pastures where cattle once grazed. Historically, ranchers in this area have depended on public grazing leases to make a living. But those leases are superseded by mineral development, and the Turner family has lost thousands of acres to mining. This is – or it was – a landscape of rolling grassland, punctuated by rugged breaks where mule deer took shelter. But the contours of the land have been altered to get at the coal. By law, the coal companies are bound to “reclaim” the land when they’ve finished mining it.

Alpha Coal's Eagle Butte Mine is close to the city of Gillette, Wyoming. (Photo: Clay Scott)

TURNER: The coal miners over here whenever they first moved in and started taking our pastures, they said: “Oh, you just wait until we’ve reclaimed this land. It’s going to be so good you won’t believe how good it’s going to be,” and that’s been…thirty years ago, maybe? And our cows have never had a mouthful of reclaimed grass in those thirty years.

SCOTT: Of even greater concern, says L. J., is the steady drying up of local water sources, which he attributes to coal mining.

TURNER: Are they going to be able to reclaim these aquifers and the creeks? Because I don’t think they can. They say they can, but all they’re doing is talking theory. And here I’m living the practical thing.

[SOUND OF RIVER]

SCOTT: In western Montana, at his home along the Bitterroot River, I met Bill Ritchie. He’s someone who’s given a lot of thought to the impacts of western coal mining on water. Over more than 20 years he managed several mines in the Powder River Basin.

RITCHIE: There are problems. There are water problems; there are things that are hard to replace, and hard to reclaim. The really complex stuff was the environmental issues: tracking the water, trying to de-water, trying not to pollute streams. Really took a lot of work, a lot of effort, and a lot of money.

J.D. Dietsche works as a coal shovel operator at the Eagle Butte Mine. (Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: When Bill first started working in coal, he says, western mines were being applauded for producing a product that was much cleaner than eastern coal. But toward the end of his career, he told me, he started to reexamine some of his assumptions about coal mining.

RITCHIE: We didn’t understand the impact on the atmosphere, and the greenhouse gases. We didn’t understand mercury as well, or the problems it creates in people’s health just burning it. We worked on clean coal projects from the time I was first starting in the coal business. And they still are working on ‘em. There is no such thing currently as clean coal. But the net result is still polluting the atmosphere.

SCOTT: All coalmines, says Bill Ritchie, including the ones he managed, begin by taking the coal that’s closest to the surface, and easiest and cheapest to get at. As the mine goes longer in its life, the coal will be deeper, and thinner seamed, and more costly to recover.

L.J. Turner overlooks grazing land that he lost to the coal mining industry. (Photo: Clay Scott)

RITCHIE: Hopefully someday they will figure out a technology on a commercial scale that can burn coal cleanly. But what a pity if we’ve mined all the coal, burned it, polluted the hell out of everything, and then when it’s time, when we have the ability to burn it well, we don’t have the resource.

SCOTT: Bill Ritchie says the type of clean coal technology he’s talking about, is not likely to be perfected anytime soon. In the meantime, coal, that powerful and dirty and much debated black rock, is certain to remain a feature of the economy and landscape of the West for many years to come.

In Gillette, Wyoming, I’m Clay Scott.

[MUSIC: Mark Ishan, In Half-Light of the Canyon, A River Runs Through It Soundtrack, Allied Filmmakers, 1992]

CURWOOD: Clay Scott of Mountain West Voices was also the producer of this team report on coal, in association with the Allegheny Front, West Virginia Public Radio and High Plains News.

Links

Breaking Beans: a storytelling project that tells the story of food and farming in east Kentucky

Ivy Brashear's Renew Appalachia: stories of transition

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth