Discovering the Lost World of the Old Ones

Air Date: Week of May 29, 2015

Ancestral Puebloan granaries high above the Colorado River at Nankoweap Creek, Grand Canyon. (Photo: Drenaline, Wikimedia CC BY-SA 3.0)

The arid climate in parts of Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico helps preserve its fragile history. So when author, climber and explorer David Roberts traveled and traversed into remote parts of the southwest, he found undiscovered evidence of the ancient peoples who lived there over many centuries. And as Roberts tells Living on Earth's Helen Palmer, these civilizations are still mysterious, but the struggle between preserving their buildings, art and artifacts in situ and the pursuit of knowledge is multifaceted.

Transcript

CURWOOD: David Roberts is a climber and explorer – and author of books on subjects as varied as Mount Everest, the Mormons and the Apache wars. But one particular book that he wrote twenty years ago caught the public imagination. It was called “In Search of the Old Ones.” It detailed his explorations and discoveries of sites in the southwest of the US, parts of Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado, where ancient peoples had lived, and built dwellings and storehouses in remote and inaccessible canyons. Well now David Roberts has revisited those areas in a recently published book “The Lost World of the Old Ones,” and Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer visited him.

PALMER: David Roberts, I'd like to start with "The Old Ones"...who were they?

ROBERTS: Archaeologists since the 1930s have broken the southwest into four main groups of old ones: the Anasazi were the most studied, in the central four corners area. North of them: the Fremont. Southwest of them among around Phoenix: the Hohokam, and we know that the Hohokam became today's Tohono o'Odham, and then directly south and into Mexico, through most of New Mexico into Mexico: the Mogollon, and we have no idea what happened to them. The reason for these four distinctions is that the material culture is entirely different, for instance, the Hohokam built canals; the Anasazi didn't. The Hohokam cremated their dead; the Anasazi buried them on their side with their knees flexed up to the chest. Fremont granaries are top loading; Anasazi granaries are frontloading. But they're reasonable distinctions and they worked for 70, 80 years.

PALMER: And their pottery styles are different too.

ROBERTS: Yes, you get different pottery styles not only century by century, but Mogollon and Anasazi pottery don't look anything like each other.

PALMER: I thought that the people who built the rock dwellings in places like Chaco Canyon and Canyon de Chelly and places like that were known as the Anasazi, but you write that's an inappropriate name. Can you explain this?

PALMER: Well, it's a question of political correctness, and unfortunately Anasazi I think is a perfectly good name but certain Puebloans objected to it because it's a Navajo word which means something like “ancient enemies” or “enemies of our ancestors.” And so in the last 15, 20 years, there's been a move to outlaw the word and substitute for it “Ancestral Puebloans.”

Monument Valley in northern Arizona and southern Utah. (Photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0)

PALMER: But that too is inappropriate because Pueblo is...

ROBERTS: ...Spanish, yeah!

PALMER: And there weren’t any Spanish here at the time they were building these!

ROBERTS: Of course not!

PALMER: So what were these people in this area really called? Or is there a better way to define them?

ROBERTS: We don't know what the Anasazi called themselves. If we did, we'd use it. It's a little bit Eskimo and Inuit, but at least we have living Inuits, who can tell us what they call themselves, but we're at a loss for a good term.

PALMER: We're looking at an area where there were ancient civilizations going back many years BC, in fact.

ROBERTS: Yes.

PALMER: What do we know with the various pre-civilizations who were there as? What are we calling them?

ROBERTS: We divide the pre-history of the Southwest into Paleo Indian, the very oldest, going all the way back to Clovis archaic which begins about 6500 BC and then you get first basketmaker and then you get Puebloan, or Pueblo, although they're all one people. So we can't tell how long the Ancestral Puebloans were in southwest, but as far back as we can trace them, they were there, unlike the much more recent tribes such as Navajo, Apache, Comanche, Ute, who were in the southwest only within the last 1,000 years at most or maybe 500 years only.

PALMER: They weren't the people who displaced the Ancient Puebloans?

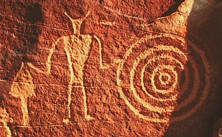

Fremont petroglyph from Dinosaur National Monument (Photo: J. Q. Jacobs, CC BY-SA 2.5)

ROBERTS: No, it's interesting. When the first ethnographers saw the empty cliff dwellings, they assumed that some other people had chased the Anasazi out, fought with them, banished them, but there's no evidence that they overlapped at all. So what seems to have happened, the great abandonment just before 1300 AD was a case of Anasazi on Anasazi violence, raiding, maybe even warfare - caused by really hard times - famine, drought, depletion of big game - all kinds of environmental factors. But the puzzle is that the Anasazi survived worse droughts before that and the climate was basically the same then as it is today, so something happened at the end of the 13th century that did cause this total and massive abandonment. It's not a disappearance; it's an abandonment. We know they went south and east and in some form became today's Puebloans.

PALMER: Now, a lot of your book focuses on discovering some of these very hidden architectural features, a lot you call granaries, but also some of them are places that were obviously spiritual places, dwelling places, tell me a little bit about these kinds of trips to discover these very hidden places.

ROBERTS: My book is not simply a popular archaeology book; it's a quest narrative of some sort because what I have been doing for 25 plus years is hiking into really remote canyons looking for rock art and ruins that almost nobody knows about. The archaeologists don't really get out and do this so much. They dismiss the sites as marginal and unimportant. And also, the Anasazi - if I may use the word again - they were brilliant climbers. So I was immediately drawn to the incredible feats that the old ones did to get to granaries and dwellings way up vertical cliffs that look incredibly difficult to access today.

PALMER: So, I mean, you describe various ways that they did manage get to the granaries, and the granaries they were building because of the drought, because they needed to store corn?

ROBERTS: Most of the really inaccessible granaries date from the 12th and 13th centuries when times are tough, and the idea is that the most precious thing is your food. You've got to keep the food away from other people, so you put the granaries in the hardest to get to places. We've gotten to granaries that, it was everything we can do to get to them and somehow the ancients not only got there, but they hauled up stones and mud to make the granaries. They hauled up their corn and beans and squash to fill the granaries. They climbed back up to retrieve the stuff regularly. It's a profound mystery.

PALMER: Now, you talk about how many of these places have been preserved by a very strange cast of characters, some of which where ornery ranchers. Tell me about Waldo Wilcox.

ROBERTS: Waldo Wilcox is one of the heroes of the book. He owned a spread in Range Creek in central Utah near the Green River for 50 years. He kept everybody out. And unlike almost all other ranchers in the west, he didn't gather up keepsakes when he found them - what he calls “Indian stuff” on the ground. He left it where it was. He had this just instinctive idea that it was not his right to mess with the Indian stuff. And when after 50 years he sold his ranch to state of Utah and the archaeologists had a look at it, they were absolutely dumbfounded because here was the most pristine valley archaeologically speaking in the whole west, maybe in the whole contiguous United States. But that unleashed some really rancorous disputes among the various parties interested in it. The state of Utah Department of Wildlife wanted to turn it into a hunting/fishing preserve. Fortunately the archaeologists won out, but then they started gathering up everything that Waldo had left in place. And to Waldo's great, and my great dismay, they applied sort of 50 year old techniques: scooping everything up and putting in plastic bags and taking it off to Salt Lake City. And you know, I think, if you have artifacts in a museum drawer where nobody ever looks at them, it's not much different from looting them.

The Black Hole of White Canyon in Cedar Mesa, Utah. (Photo: Dave Riggs, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

PALMER: So the area that Waldo protected which was very pristine is now just like everywhere else?

ROBERTS: Range Creek hasn't been severely looted. There has been some looting by outsiders, but the effect of the archeological team has been to strip it of most of at least most of the surface artifacts. They haven't done a lot of digging yet. It's still an incredibly rich place. It's not as denuded as much more vandalized, hammered mesas and buttes and canyons elsewhere in the southwest, but it's sure isn't what it once was—what it was in 2001. It's a tragedy, I think. Range Creek by the way, is not Anasazi but rather Fremont, which is the northern neighbors of the Anasazi, and so much less is known about the Fremont that this is all the more important. But the history of archaeology in the southwest is rife with cases where major excavations over 20 years ended up with a chief archaeologist never writing it up and that is the worst kind of destruction and loss you can have.

PALMER: Now, your first book which was called, "In Search of the Old Ones," it caught the popular imagination, but it earned you a degree of opprobrium among archeological fraternity. Can you explain that?

ROBERTS: Yes, I had no idea. "In Search of the Old Ones" was published in 1996 and I began the book with an account of discovering a pot in a small canyon on Cedar Mesa. And I ended with discovering with my wife Sharon an amazing basket, 1500-year-old basket, in another canyon on Cedar Mesa. But I didn't give any directions or any hints where these things where. I wasn't going to give away their location. It was just about how amazing it was to find them. Well, what I simply failed to anticipate was that my book would be used as a treasure map and people would show up with copies in hand at Kane Gulch ranger station and ask the rangers or demand of the rangers, "How do I get to Roberts' pot?" and this caused a kind of backlash. And even today, I get grief from some of the aficionados, who think that I'm popularizing places like Cedar Mesa and contributing to their ruination.

PALMER: Well, you found exactly the same thing when you went to one of the early places that you'd been to, that you had written about.

Anasazi petroglyphs at Petroglyph Point, Mesa Verde National Park (Photo: Frank Kovalchek, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

ROBERTS: Oh, I've seen so many sites that were once rich with artifacts potsherds, lithics that have been stripped completely, but that's inevitable. That's been happening since 1870 in the west in places like Blanding, Utah, they used to go out on Sunday and just dig up ruins for fun, Sunday picnics, even though it's all totally illegal and was even after 1906. But it's really dismaying to go to a site that you once saw that was so rich in things and to find it stripped. That's why I wrote this op-ed piece for the New York Times, arguing that even though I sort of hate the idea of turning Cedar Mesa into a national moment, that may be the only way to save it.

PALMER: Well, why isn't a national monument a good idea? Doesn't this, in fact, preserve places?

ROBERTS: National monuments inevitably bring hoards of people. Right now, Cedar Mesa sees 70,000 visitors a year. It sounds like a lot. Grand Canyon sees four and a half million. Rocky Mountain National Park sees four million. Yosemite: four million. If you make Cedar Mesa a national park it will at least see 500,000, and a lot of them won't know what they're doing. And also there will be all sorts of rules and regulations about what you can do and can't do, but as it stands now under the Bureau of Land Management, there's just no way to protect it. There's two rangers to police 600 square miles of outback. Not possible.

PALMER: And in fact there are movements in Congress and there've been new regulations in the Utah state Congress that do open these places up and want to open these spaces up.

ROBERTS: Three years ago, the Utah Legislature passed a bill demanding that all federal lands in Utah except the national parks, the five national parks, be turned over to the state. The governor signed it and they made a deadline of December 31, 2014. And when that day came and passed and the feds didn't turn over the land, they renewed their efforts; they devoted $2 million to try to bring a lawsuit. And the only thing that may stop this is if some court declares the law unconstitutional, which we all hope, but I was really shocked just this winter, to find that the US Senate voted 51 to 49 in February to encourage the states to do the same thing. I hate to say it, but it's a Republican era, and Republicans don't believe in federally protected land for the most part.

PALMER: Well, they do argue that it is the states rights to have the value and the use of their own lands.

ROBERTS: Gosh, no. Not at all. I'm appalled by the fact that the US is one of the few countries in—maybe the only country in the Western Hemisphere—in which you are allowed to dig anything you want, unless it's a burial, on private land. If you're in Guatemala or Mexico and you discover an ancient tomb or even just a settlement, it belongs to the government. You have no right to dig it up. If you have a dolmen in your backyard on your country estate in England, you have to allow the public access to it. You can't fence it off and put up no trespassing signs. We, Americans, put such sanctity on private property that we allow this kind of what really is looting to go on under the claim that it's private land, and you can do what want with it. You can go on eBay and look up Anasazi pot and you'll find all kinds of beautiful vessels. And everyone will say we have a deed proving this was dug on private land. Well, that's just nonsense. A lot of them were looting from BLM land from state forests, but how do you disprove a fake title?

PALMER: Well, you say that it's not a great idea to make things a national monument because then all the people will come, but is the alternative to do as they've done with many of the prehistoric caves, with cave paintings, say that no one can ever go into them?

ROBERTS: Like Lascaux, yeah. I fear that may be the ultimate solution in the southwest, that places like Betatakin and Keet Seel--some of these great ruins--we simply won't be allowed to visit them anymore. I mean, even now, on Mesa Verde, there are perhaps 400 ruins and you're allowed to visit two or three of them. The other 397 are off-limits to the public.

Together with his wife, Sharon, Roberts found a 1,500-year old basket in Cedar Mesa. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: But a problem you point to is that the BLM has insufficient manpower, insufficient funds, and that isn't likely to change at least with the present Congress we've got.

ROBERTS: The present Congress would probably like to do away with the BLM altogether. The big advantage of a national monument is it would mean much greater staffing, much greater money to take care of the place. You do have four and a half million people in the Grand Canyon, but you actually don't have very much looting because of the manpower and the financial resources. You may have overcrowding, but you don't get the kind of desecration that you get on BLM lands all over the place. But the reason I pushed for a monument in my op-ed piece for the [New York] Times was because the president can decree an national monument - and Obama has been doing it - but a national conservation area requires a vote of Congress, and the way Congress is trending, I think there's no chance in hell that they'll make Cedar Mesa a national conservation area, or any other good place.

CURWOOD: That’s David Roberts, author of “The Lost World of the Old Ones” in conversation with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Well, the questions the book raises are deep, even philosophical and we’d like to know what you think. How should we protect fragile lands and their irreplaceable archaeological heritage?

The US Senate recently passed a resolution stating that public lands not designated as National Parks or Monuments should be managed by the states. But some say that approach would mean opening these historic sites up to mining and other commercial interests. On the other hand, many in those Western states say they know their territory better than the federal government and can do a better job of protecting this heritage.

So please tell us what you think. How should America protect this heritage and who should be in charge?

Please go to our website LOE.org and find the comments section at the bottom of the transcript for this story, where you can see what other listeners have to say - and put in your two cents. Or just send an email to comments@LOE.org – that’s comments@loe.org. Or call our listener line at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988, and be sure to tell us how we can reach you.

Links

Saving What’s Left of Utah’s Lost World

More about Roberts' "The Lost World of the Old Ones"

Utah's Bureau of Land Management

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth