US House Votes New Fishing Rules

Air Date: Week of June 5, 2015

The pollock fish stock in Alaska is in good shape, thanks to the Magnuson-Stevens Act. (Photo: NOAA FishWatch)

Before 1976, global fishing was largely unregulated and foreign trawlers were depleting American fisheries, providing the impetus for the Magnuson-Stevens Act. The Act’s strong federal management standards implemented by regional councils have helped national fish stocks recover. But as Andrew Rosenberg of the Union of Concerned Scientists tells host Steve Curwood, the Act is up for reauthorization, and the changes passed by the Republican-led House of Representatives would improve monitoring but could also weaken protections.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The oceans cover over 70 percent of the Earth and they contain more than 95 percent of its water. The seas regulate our climate, feed billions, and provide half of the oxygen we and all the other creatures need to breathe. The UN designates June 8th as World Oceans’ Day, and that’s why they’re the focus of today’s program. This year’s theme is Healthy Oceans, Healthy Planet, and one area of crucial importance is the health of seafood. Since 1976 the US has relied on the Magnuson-Stevens Act to protect fisheries, first extending national waters to 200 miles to exclude foreign trawlers, and later setting sustainable catch limits. Well, the Republican-led House of Representatives just reauthorized Magnuson-Stevens to include such new technologies as electronic monitoring. But critics say some changes could hurt sustainability, and the President has promised a veto. Andrew Rosenberg is a former northeast regional administrator of the National Marine Fisheries Service, and joins us. Welcome to Living on Earth, Andrew.

ROSENBERG: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Andy, for listeners who aren't familiar with the Magnuson-Stevens Act, tell us what it is, where it came from and how it works.

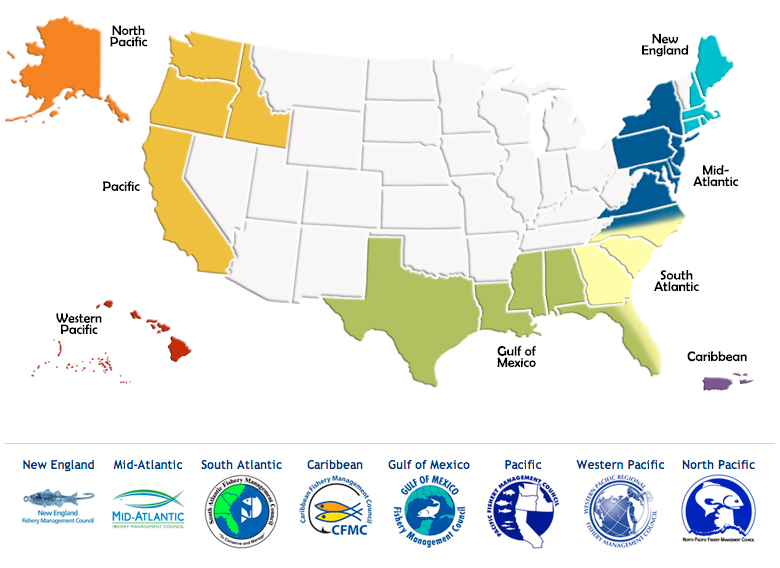

ROSENBERG: Well, originally it declared a 200 mile limit back in 1976 and then internationally the UN agreed in the Law of the Sea convention a 200 mile limit for all coastal states, but it also then set a set of management criteria for US fisheries within 200 miles of our coast. It gave authority for management to joint authority between the National Marine Fisheries Service and a set of regional fishery management councils. It's actually a quite unique structure, and those regional management councils are populated by representatives from each of the states and representatives from the affected industries, and sometimes those from other groups, including conservation groups. And those councils are charged with developing management plans for US fisheries.

CURWOOD: So how have these fisheries management plans worked over the years, in general, and then be specific about a couple, if you will, please.

ROSENBERG: Well, if you look back through history, initially we pushed all the foreign fishing vessels out at different rates in different coasts. Each of the regions did things slightly differently, but unfortunately in many places we replaced foreign overfishing with domestic US overfishing, and so that resulted in depletion of resources on most of our coasts. And over time the law has been modified to try to end the problem of overfishing for US fisheries — quite successfully, I would note, although it took us 30 years to do.

CURWOOD: Why do you think the act has been more successful in certain regions than in others?

There are 8 fisheries management councils in the US that work with the federal government to conserve fisheries and manage public and private interests. The councils are comprised of scientists, commercial and recreational fishing sectors and conservationist groups, among others. (Photo: National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA)

ROSENBERG: There's a number of important reasons. One is the starting position. The act has been very successful in Alaska and maintaining the fishery, but they had a really good starting position, effectively, for the pollock fishery, which is the dominant fishery, as well as crabs and others. They were not in an overfishing situation, whereas in New England, already there were very substantial depletion. A second reason is really regional culture, and how the councils were set up, and what their ethos was when they were set up, and so each of the councils has had different resource problems to deal with and different biology of the species, incidentally, but also a different culture within the council about what they view their job as.

CURWOOD: So we've had these revisions of Magnuson Stevens. What's going on with this recent effort to reauthorize it?

ROSENBERG: Well, the reauthorization effort now is really part of a push to change the way the authority for regulation works overall, from a federal government lead, to more authority to the regional management councils and what is labeled as “greater flexibility” in the law, so that those councils can address problems in different ways and different timelines. What it's doing is backing off on the strong standards that are in the law that the councils have had to meet — and, frankly have resulted in our ending overfishing — in the name of giving greater authority and flexibility to these regional bodies.

CURWOOD: Let me see if I understand what you're saying. In your view, the recent legislation to reauthorize Magnuson Stevens would weaken the protection of America's fisheries.

ROSENBERG: Correct, in my view, that's very much the case, that it would certainly weaken protections. For example, the law currently says if a fish stock, marine resource, is overfished — in other words, too much fishing pressure — without getting into any of the technical details, you should if it all possible, if it's biologically feasible to do so, rebuild that resource within ten years. That sets a strong timeline by which the councils must create a management plan. Now, in fact there's quite a lot of flexibility in there, but having that deadline is really quite important. The proposed modifications to the law would say, “well, we don't really need to restrict it to ten years, we can give the councils more flexibility, they can phase-in reductions in fishing pressure to account for economic factors.” Even though almost every analysis I've ever seen or ever done indicates that phasing in is an overall negative both economically as well as for the resource, because, unfortunately, the fish aren't there to wait as you decide you want phase in and make adjustments more slowly; if you continue to overfish, you continue to deplete the resource. So that's just a bad idea. You need to hold people to tighter timelines.

CURWOOD: Why weaken this law if, in your view, it's been so successful?

ROSENBERG: In every stage of the management process, it's always going to be contentious because you're telling people they can't do things that they want to do, because you're trying to manage for the public good, not for an individual entity or business. But one way to deal with a very contentious situation is to call for more flexibility, “Well, we'll take several more years to phase this in, so it'll ease the pain," even though that doesn't really work. And so that's one of the reasons.

Andrew Rosenberg is the Director of the Center for Science and Democracy with the Union of Concerned Scientists. (Photo: Courtesy of the Union of Concerned Scientists)

A second reason, and actually a really, I think, dangerous part of the proposals that are being put forward are that it would give the Magnuson-Stevens Act some primacy over -- essentially overriding other laws that regulate environmental actions, including the National Environmental Policy Act, and the Endangered Species Act, the Sanctuaries Act, and so on. The fisheries councils would basically substitute for those laws, and that's a really dangerous thing to do, because you can imagine that many other industries — energy industry, shipping industry, coastal development — would all say, “Well, gee, if the fisheries management councils could do this, then we don't really need to be subject to these rules either, because we can do an equivalent analysis." But that means that we're undermining the basic environmental protections that we have in the country, that actually have made a difference. And the consequences of that, I think, are really dire.

CURWOOD: Andrew Rosenberg is the Director for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thank you so much for taking the time today.

ROSENBERG: Thank you, Steve. I really enjoyed it.

Links

The House passes Magnuson-Stevens Act reauthorization

US Regional Fishery Management Councils and rules

More about the Magnuson-Stevens Act, amended 2007

National Marine Fisheries Service involvement with the Act

Tracking commercial fishing vessels, globally

Reauthorization Status of the Magnuson-Stevens Act

“House bill would add 'flexibility' to federal fishing law”

Andrew Rosenberg’s work with the Union of Concerned Scientists

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth