The High Human Cost of Cleaning Up Boston Harbor

Air Date: Week of June 5, 2015

By the time it was completed, the outfall tunnel contained oxygen-starved, toxic air that would be deadly to anyone who breathed it. (Photo: MWRA file photo)

Over budget and behind schedule, engineers raced to complete Boston’s Deer Island Treatment Plant. The final step before the treated wastewater outfall tunnel could be operational was to remove the plugs to release the cleaned water into the sea. Author Neil Swidey’s book Trapped Under the Sea relates the story of the five men who were sent on this ill-planned and untested task. Swidey joins host Steve Curwood on Deer Island to explain what went wrong, and the lessons learned.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Well, Dave Duest mentioned the deep rock tunnel that channels the cleaned water nearly ten miles under Boston Harbor. It was an engineering feat that had a human cost as well. Boston Globe writer Neil Swidey chronicles this story in his recent book, "Trapped Under the Sea: One Engineering Marvel, Five Men, and a Disaster Ten Miles Into the Darkness." It tells the story of a group of divers whose lives depended on untested technology and questionable decisions, with deadly consequences. And overlooking the now sparkling harbor from Deer Island, he told us about it.

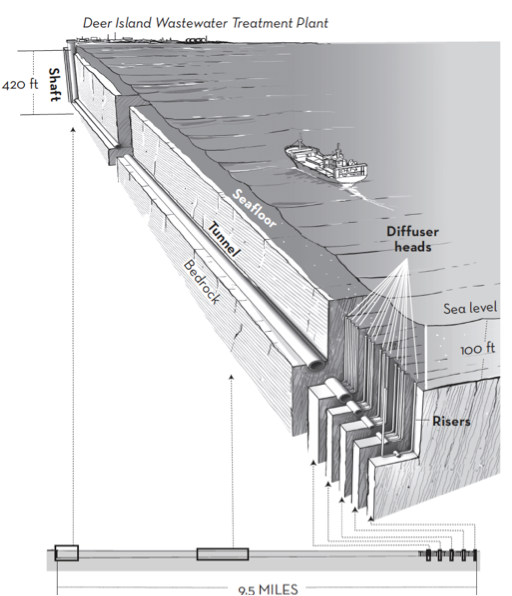

SWIDEY: I was fascinated by this story that I didn't know about, and that most people even here in Boston didn't know about, which was the final piece of this massive cleanup of Boston Harbor and the people who put their lives on the line to create this beautiful harbor that we see today. After building this massive, sophisticated treatment plant, there was the construction of the world's longest tunnel of its kind. It sends the treated wastewater out into the deep Atlantic waters of Massachusetts Bay. That tunnel, and the final piece of that tunnel, was the subject of the book.

The outfall tunnel carries effluent, or treated wastewater, from Deer Island Treatment Plant nearly 10 miles out into Massachusetts Bay. (Photo: courtesy of neilswidey.com)

CURWOOD: You write about the people who worked on that last bit and the accident that happened. First tell me, what was the set-up. Why, in your view, looking back, was this an accident waiting to happen?

SWIDEY: It's fascinating. This project here that did this miraculous conversion and transformation of this harbor, taking the nation's dirtiest harbor, turning it into its cleanest urban harbor, it was a remarkable transformation. The people who worked on that were some of the best and the brightest minds in the world, and they made a host of good decisions over a decade, but at the end they made some serious and tragic bad decisions that forced a group of blue-collar workers to risk their lives to rescue this project.

CURWOOD: What exactly did these blue-collar workers have to rescue?

SWIDEY: So at the very end of the tunnel, it chokes down and it goes from 24 feet wide to just five feet in diameter. The whole point is this massive tunnel moves up to a billion gallons of treated wastewater through every day, and yet it doesn't use a single pump or electrical source — it's all gravity that moves that effluent through the tunnel every day.

While the project was being built, there was a series of safety plugs at the end to protect the sandhogs, the tunnel workers, for the decade that it took to build the tunnel. Nobody figured out how those plugs were going to get out. At the end, when this project was over-budget, past deadline and under federal court order to meet these deadlines, there was an enormous amount of pressure, an enormous amount of infighting among the various contractors and subcontractors, managers. Nobody could get along. Trust had gone down on the project. The powers-that-be looked for a rescue artist to come in, and that was a team of commercial divers who were going to go into the tunnel, which by the way at this point had been removed of all of its life-support, the oxygen, the lighting, the transportation. All those systems had been removed, but the tunnel wouldn't work unless these 55 safety plugs, these stoppers at the end of the tunnel, were removed.

Five divers were sent into the tunnel to release 55 safety plugs that would prevent the tunnel from flooding in the event that a diffuser head was damaged. Without the plugs’ removal, the outfall pipe would not be operational. (Photo: courtesy of neilswidey.com)

CURWOOD: So somebody had to go down there and get those corks out. Some divers were hired. Doesn't sound so bad at this point, but I guess it went bad. What happened?

SWIDEY: Well, basically, divers were asked to do something that never been done before, because this was so far out, so remote and so confined, this space at the end of the tunnel, just five feet in diameter. In fact, those plugs were nestled in connector pipes that were 30 inches wide, so just slightly wider than our shoulders.

CURWOOD: Well, wait a second...I'm going to say...how does somebody get in there?

SWIDEY: They had to crawl in there, and the most fundamental source of risk on this was that it was too far out to bring conventional air supply that divers would be used to — high-pressure bottled air. You'd use up all your supply just getting out to this remote spot, and you wouldn't have the time to crawl into these slimy connector pipes in pitch black and remove these.

CURWOOD: So just to be clear, there's air in this tunnel, but apparently it's not air anyone can breathe.

SWIDEY: Yes, the tunnel hadn't been filled yet, so they didn't send in divers to swim into the tunnel. They sent in divers because they guys know how to do dangerous jobs in environments where they have to bring in their own air. At this point, deep into the tunnel a decade after it was being built, one or two breaths of the ambient air would be fatal, it was oxygen-starved, toxic air. And so the divers had to bring in their own breathing gear, something that they're used to. But the air they're used to has been tested, it's bottled air, it's a supply that you can trust. This was too far out, so this hotshot engineer that they hired came up with this plan to mix liquid oxygen and liquid nitrogen right there in the tunnel and turn that into breathable air.

The five men traveled as far as they could in the narrowing tunnel in two Humvees they’d brought – one towing the other backwards. Since there would be no room to turn a Humvee around, they planned to abandon one vehicle and drive the other back when their dangerous mission was complete. (Photo: MWRA file photo)

CURWOOD: This hotshot engineer gets the job as the lowest bidder?

SWIDEY: He gets the job really as the only bidder. The contractor cast about and they found a couple of people who came and toured this and said, "Sorry, no thanks. I don't care how much you're paying, it's not worth it. I can't do this safely." But this one engineer came in and said, "I can get you out of this jam and I've got this innovative cutting-edge plan to do this." But he didn't go in. He sent in this team of five divers, and not all of them made it out alive, tragically.

CURWOOD: So what happens?

SWIDEY: So five divers go into the tunnel. They take these converted Humvees — two of them, one towing one in the opposite direction — because once you get in, there's not enough room even to open the doors all the way, so you just take the other one heading back the other direction when you want to get back.

CURWOOD: This sounds bad already.

SWIDEY: Yeah, but then the Humvee could go only so far. Two of the divers would stay in the Humvee monitoring the breathing system for all five, while three proceeded on foot using umbilicals, hoses that were connected into the main system, and they went out into the dark to try and get these plugs out.

CURWOOD: So what exactly happened?

Since the air in the tunnel was so toxic, the divers needed to bring their own air. But their air supply system, which had never before been used on a project, malfunctioned – proving deadly for two divers. (Photo: MWRA file photo)

SWIDEY: This experimental breathing system that hadn't been fully thought through failed. At the very end, when the three-man excursion team who were on foot crawling, went into these narrow pipes and they pulled a couple of plugs out, and the foreman of that crew looked up at that one point and all their umbilicals had become tangled because it was so confined and there was so much crawling around back there and he said, "Let's stop and let's iron these out, let's get our things straightened out." And as that was happening, he looked in horror to see one diver collapse onto the tunnel floor and another one go right there. So he lunges for a safety valve to switch the divers to a back up system, and then they try to connect with the divers who were back in the Humvee to see what the oxygen percentage was. And, as you know, the oxygen we breathe is not 100 percent, it's 21 percent oxygen, but if it drops very far below that 21 percent, bad things happen. And he knew that if that percentage was below 16 percent they were in deep trouble, and so he said, "What's the oxygen percentage?" and they said, "We'll have to check,” because the system was so jerry-rigged someone had to leave the Humvee to check the pressure valves and come back. And then he reports back that it's 8.9 percent and then the line goes dead.

CURWOOD: So we know the story. So that means that some of them got out alive, but not all, I gather. How did the ones survive?

SWIDEY: Three drivers made it out alive, two tragically did not, but one of the most jarring revelations for me was how close it came to all five divers perishing — it was 30 seconds — 30 seconds, had that foreman not reached for that backup valve when he sensed trouble, all five of them would have perished.

CURWOOD: Well, surely, in these modern times we would've had the capability to not have that. How the heck did this happen in the face of how smart we're supposed to be?

The Living on Earth crew on-scene as host Steve Curwood speaks with author Neil Swidey. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

SWIDEY: Yes, well, I think it happened because of organizational failure at the end of this project. When you have a situation where the contractor and the manager and the owner aren't getting along, you have to fix that, because if you don't fix it then this is what can happen. You have a lot of people who are responsible for this amazing project here who don't like talking about it because of how this ended, and that's a tragedy. They should be taking bows at conferences about what the success story was here, of how remarkable this transformation was here, and that means managing it all the way through. After the tragedy of the accident, the leader of the MWRA, Doug McDonald at the time said, "tensions and finger-pointing got us into this mess and worries about costs and who's going to pay what got us into this mess, so we're going to take money off the table and we are going to use our bright collective minds here to figure out how to solve this in a creative innovative way. And then we'll worry about money after that." And that gave people the permission to think creatively and come up with this innovative solution that ventilated this tunnel, got air back into the tunnel in this brilliant engineering solution that no one had thought of before, and those plugs came right – pop, pop, pop — out, in two days. The tunnel was operational and this transformation was allowed to begin. So the challenge, I think, for people looking at this is, how do we get that post-tragedy realization of, "we've got to work together here,” without suffering the tragedy?

CURWOOD: And there's a memorial for these men.

Neil Swidey is an award-winning staff writer for The Boston Globe Magazine and teaches at Tufts University. His other books include The Assist and Last Lion: The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy. (Photo: courtesy of neilswidey.com)

SWIDEY: So the five members of the team – DJ, Hoss, Riggs, Billy and Tim — all put together and asked to do this impossible job. Hoss, Riggs and DJ who were the furthest out, made it out alive. Tim and Billy did not. But those three who survived, that risked their lives more by bringing the bodies of their fallen team-members back, they added much more time to their already narrow escape path in order to bring those bodies home with dignity. And today, on this island, there are plaques to Billy and Tim, and there are memorial benches on this path that rings the island of bikers and walkers and roller-bladers and you can sit and look out directly above that ten-mile path of that tunnel. And you see that clean water, and you can think about those two otherwise anonymous workers, Tim Nordeen and Billy Juse and say "thank you" to them to the work that they did and that we all benefit from.

CURWOOD: Neil Swidey's book is called, "Trapped Under the Sea.” Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SWIDEY: Thank you, Steve. My pleasure.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth