The Quest for the ‘Asian Unicorn’

Air Date: Week of June 19, 2015

“Martha” was the first adult saola to be observed outside of its habitat. Conservationist William Robichaud gave her the name while observing her over a period of two weeks in 1996, when she was briefly held in captivity before she passed away. (Photo: William Robichaud / WCS)

Deep in the forests of Southeast Asia lives a creature that, in profile, looks like a unicorn, but it’s almost as rare as that mythic beast. The saola is related to wild cattle, but little is known about it, except that it and its habitat are disappearing. In this conversation, author William deBuys discusses his book The Last Unicorn with host Steve Curwood and explains his quest to the jungles of Laos in search of the rare saola.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Deep in the forests of southeast Asia lives a creature nicknamed the Asian Unicorn, and it's nearly as rare as the mythical creature, as well. The Saola has only been known to Western science for about twenty years, and its habits and way of life are still mysteries, and it is right at the edge of extinction. Writer William deBuys accompanied conservationists on an expedition to study the saola, and his book The Last Unicorn lays out the story and the challenges of saving a species so rare. Bill, welcome to Living on Earth.

DEBUYS: Thank you. It's great to be with you.

CURWOOD: Bill, please describe the saola for us. Why is it such an enigma, and why is it nicknamed the Asian unicorn?

DEBUYS: Well, the saola was discovered to Western science only in 1992. Local villagers in the habitat of the saola, of course, have known it was there forever, but this new discovery was made when scientists saw a rack of horns on the wall of a hunter’s shack, and these horns are the most distinctive features of the saola. They're long, almost straight, and beautifully tapered to a very sharp point, so that when the saola stands profile, the two horns in perspective merge into one, and it appears to have only one horn, it appears to be a unicorn. Perhaps only dozens to a few hundred still exist, and there are none in captivity.

Juvenile saola held in captivity in Hanoi, 1993. (Photo: J. C. Eames)

CURWOOD: So what’s its color, how is it marked?

DEBUYS: Well, it's a beautiful animal. It has camo splashes of white on the muzzle, which may vary from individual to individual. Its body is kind of a brown almost and it has stripes of chocolate brown and white and black on its rump, which match perfectly with similar stripes on its tail. It's a somewhat stocky animal, about the size of a carousel pony. The saola is a bovid, which is to say it has cloven hooves and it chews a cud. Its nearest relatives in evolutionary terms are wild cattle, but they're really not very close relatives. The saola seems to have branched off the evolutionary tree quite on its own a very, very long time ago. One of the most striking characteristics of the animal is its seemingly serene disposition. My companion on the expedition, Bill Robichaud, was in the company of a captive saola for two weeks in 1996, and this animal was so tame in his presence that he was able to pick ticks out of its ears. He said it was tamer and more serene than any farm animal than he had ever encountered.

CURWOOD: Describe Bill Robichaud for us.

DEBUYS: Well, he's a rugged and funny fellow, and he is as passionate and energetic in the protection of wild animals — right now chiefly saola — as any person on this planet. He came to conservation through a fascination with birds, and as a teenager he climbed a tall oak tree and captured a young red tailed hawk and became a falconer. The hawk was named Genghis and led Robichaud on many a hilarious escapade. He continues to get back to Laos multiple times each year. Right now he is the coordinator of the Saola Working Group, a committee of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, and the Saola Working Group is the chief body working to protect the saola from extinction.

Expedition leader and conservationist William Robichaud has been working on wildlife conservation and research in Southeast Asia for nearly 25 years. (Photo: William deBuys)

CURWOOD: So this is, well, this is an amazing adventure story. What was this journey like for you?

DEBUYS: Well, it was magical in many ways. It was physically very, very demanding. The mountains were steep, the canyons were deep, the rivers were very rocky, and some days we were just climbing one waterfall after another. But we found ourselves immersed in a forest of great beauty — also great loss because of the depletion of wildlife from poaching. But the sense of beauty stayed with us all the time.

CURWOOD: Tell us what it's like there in the forest. What would you hear in the forest?

DEBUYS: Oh, the music of the forest was constantly inspiring and entertaining.

[BIRDSONG FROM LAOS]

The birdcalls never ceased. We heard laughing thrushes, and we heard drongos and Indian cuckoos and all kinds of birds with really distinctive calls. There was a kind of chorus behind us all the time.

But the most marvelous thing occurred at first light, almost every morning. We heard the calls of gibbons. Gibbons are small apes, beautiful, slender animals that swing through the trees, so gracefully, and their calls are ethereal. And they call, male to female and female to male, in mated couples, and you can think of it as almost a kind of love song that you hear echoing through the forest.

DeBuys, at left, looks upstream on a tributary of the Nam Nyang with Meet, one of the Lao guides on the expedition. (Photo: William Robichaud)

CURWOOD: Let's take a listen now.

[GIBBONS CALLING]

DEBUYS: Many a morning, I would just lie in my sleeping bag and listen and listen for as long as the gibbons were willing to call.

CURWOOD: Bill, your book isn't just a rallying cry to save a particular, a single species, it examines the broader cultural economic pressures in the forests of Southeast Asia. What are those pressures?

DEBUYS: Well, it's a land undergoing great change: manufactured goods are filtering into the remote villages deep in the forest, the pressures of poaching are rising year-by-year, as more millions of people in the expanding economies of China and Vietnam and other countries can afford to pay for expensive medicinal cures — or what they believe to be cures — that use wildlife and wildlife parts. More millions of people can also afford expensive bushmeat restaurant meals, which are a kind of source of conspicuous consumption in those societies. As economies expand, as consumer culture penetrates areas where it never had been before, the pressures on the forest are really intense.

CURWOOD: Now, why do you suppose it's people like you and William Robichaud, who come from the affluent West, where our usual and endemic species are already gone, why do you suppose you're the one writing this book rather than someone in Southeast Asia?

Poachers’ snare lines crisscross the remote forests in the mountains at the Laos-Vietnam border, capturing and cruelly killing countless wild animals. This douc, a type of primate, likely suffered for several hours before it finally succumbed to its injuries. (Photo: William deBuys)

DEBUYS: Well, you know there is a criticism that we need to take seriously, that Westerners are now telling people in Asia how to live. We haven't done very well by our biota, in our homes in Europe and in North America. But the fact is that the species diversity in Southeast Asia is as high or higher than any other part of the world. There are more endemic species, which is to say species that occur only there, and a higher proportion of those species are threatened with extinction than in other parts of the world. So if we globally are serious about conserving the biodiversity of this planet, then we really need to focus on Southeast Asia and hope that the countries there can preserve their natural heritage and learn from the mistakes that we have made in our own path into development.

CURWOOD: I think it's interesting you compare these pressures to those in the American West. Why did you choose to do that?

DEBUYS: Well, in an earlier life I was an American historian, and I was struck when I was in Laos with the plight of people who a generation or two ago were nomadic, and who have been settled in the same way that Native Americans in the US West were settled on reservations a century and a century and a half ago. When nomadic people are forced to settle down, they have to eat new foods, they have to change their ways, they lose contact with the spirits of their ancestors and their belief systems. They suffer heartbreak, they get sick, they're more vulnerable to disease, they have to encounter new manufactured goods, and often they have to encounter a whole lot more alcohol than they had had before. And the penetration of alcohol into the society can create all kinds of social functions, as it did on reservations in the US West. So there were big parallels that I was seeing, and one of those parallels was the sense that a war on nature was going on. In the 19th-century American West, we were losing the beaver from the streams, we were losing bison, the mountain sheep and elk were being decimated, etcetera. That same kind of loss of wildlife is going on in much of the forests of Asia right now.

A camera trap caught this image of a saola, which may have been pregnant, in 1999. (Photo: courtesy of William Robichaud / WCS)

CURWOOD: Bill, how much wildness still can be found in the forests of Laos today?

DEBUYS: Immense amounts of the forest are still truly wild, and we even found some pockets of the wildlife community that were almost wholly intact. And so if the government of Laos and other interested parties are able to provide the protection against poachers that these forests need, their potential to repopulate themselves with wildlife, given their productivity, is very, very high. There's an enormous amount still to save there.

CURWOOD: So what are conservationists like your expedition leader William Robichaud, what are they trying to do to save the saola?

DEBUYS: Well, first of all they're trying to identify its habitat, and as I say, very little is known about some of these forests. So these forests have to be surveyed, and once habitats are prioritized, then there is an effort to see if saola are actually there. As time goes on, there may even be an effort to capture saola and put them into captive breeding programs, so that, eventually, when areas are safe from poaching, those additional animals can be put back into the wild and repopulate the natural habitat of the saola.

In 2013, a camera trap caught this photograph of a saola. It is the most recent photographic evidence scientists have that the saola has not yet gone extinct. (Photo: WWF Vietnam)

CURWOOD: How well do you think the attempts of Robichaud and others to engage locals in saola conservation are working?

DEBUYS: Well, the progress is there. It may be slow, but it's there. Our expedition basically had three purposes: one was to look for saola habitat and for saola in that habitat. A second was to evaluate the poaching pressure on the landscape. And a third was to conduct a kind of conservation diplomacy in the villages of the forest. We talked to headmen in the villages and to groups of elders about ways that hunting might be reformed in order to protect any saola that might be there. And one of the remarkable things that Robichaud has encountered again and again, and I on one occasion on the expedition also encountered, was a conversation that goes like this. A villager says, "Do you have a lot of saola in the United States?” and we say, “No”. “Oh, well there must be many, many saola in Africa?” We say, “No, there are no saola in Africa either, or in South America. The only saola in the world are the saola right here in these mountains.” And the villager says, "Oh my,” and makes a recognition — you can see it happening right there — that saola is something to be proud of, that his world has something the rest of the world doesn't have. And the more that pride is awakened the better the prospects for saola will be.

CURWOOD: How is the saola faring today?

The expedition’s Lao guides and researchers enjoy a communal supper of rice and a soup made from leaves gathered in the forest, rattan, ginger, citrus, and garlic. (Photo: William deBuys)

DEBUYS: The saola . . . we don't really know because it's so hard to detect. But the advocates for saola got some very cheering news in 2013, on September 7, when a camera trap in Vietnam, very close to the Laos border, caught two pictures of a live saola. This is the first camera identification of a wild saola in more than 15 years, and so we know they're still out there. There's still something to strive for. There’s still this beautiful, beautiful creature that we hardly know, still moving around in that remote and very challenging environment.

CURWOOD: How many saola did you see?

DEBUYS: Well, we saw none. No Westerner has yet seen a saola in the wild, and the joke is that saola are so like unicorns, and everybody knows that in the Middle Ages, the only people who had an outside chance of seeing a unicorn had to be absolutely pure of heart. And Robichaud and I joke that if that applies also to saola, then we were disqualified from the get-go.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] This was certainly an extraordinary journey. What did it end up meaning for you?

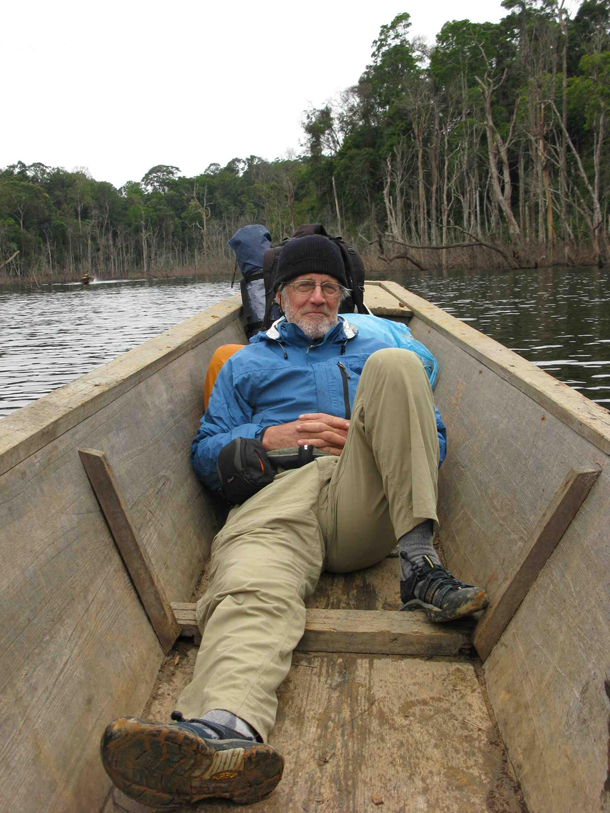

William DeBuys enjoys a moment of rest during an otherwise arduous journey. He is the author of eight books, including River of Traps, a Pulitzer Prize nonfiction finalist; Salt Dreams; A Great Aridness; and The Walk, an excerpt of which won a Pushcart Prize. (Photo: William Robichaud)

DEBUYS: Well, the book is a quest, and the quest may be the oldest form of literature in human culture — think of The Odyssey, think of Gilgamesh, of the Jews leaving Egypt and seeking the promised land — and as with a lot of quests, we didn't find what we set out to find, but we found something else. We found an encounter with deep beauty. And we also found, or I found, a sort of psychological and spiritual space in which optimism and fatalism became recognized. This is really the story of the book, and it's the story of the expedition for me. You know, if we look at the world, we see a lot of bad news, we see a lot of defeat, we see a lot of things going wrong, we see erosion of all kinds of things. But at the same time, beauty always remains. And there's a lot of beauty out there, yet to be defended, yet to be protected, and that task of protecting what remains, I think, is inherently meaningful, and that meaning is inherently optimistic. Just because you're realistic about how bad things are, it doesn't mean for an instant that you would want to give up. It only means that you want to work harder to protect what's there.

CURWOOD: William deBuys is the author of “The Last Unicorn: A Search for One of Earth's Rarest Creatures” and seven other books. He's also a Pulitzer Prize finalist and a recipient of the Pushcart Prize. Thanks for taking the time for us to talk today, Bill.

DEBUYS: Steve, it's been a great pleasure. Thank you.

[BIRDSONG FROM LAOTIAN JUNGLE]

CURWOOD: Bill deBuys recorded these sounds in the forests of Laos.

Links

About the lead conservationist on the expedition, William Robichaud

Poaching pressures in Southeast Asia impact endangered species

Tracking black markets in wildlife trade

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth