Florida's Disappearing Springs

Air Date: Week of August 21, 2015

A “jungle riverboat cruise” passes the diving platform at Wakulla Springs. (Photo: Doug Struck)

Florida’s springs are a wonder, bubbling up crystal clear from the state’s limestone aquifer. But persistent drought, agriculture and a growing population are polluting some once pristine springs. As reporter Doug Struck discovered when he returned to his favorite childhood swimming hole, Wakulla Spring is now green, murky and full of algae.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Well, this August the many Presidential candidates are busy shaking hands at the Iowa State fair, trying to sell their message to those first caucus voters, but the American public’s attention is still mostly on summer. There’s nothing like an escape to the seaside, or the mountains‚ or to other favorite places for fresh air and sunshine. But as reporter Doug Struck discovered when he took a sentimental trip back to a beloved childhood haunt, sometimes what you reveled in way back when just can’t be found again.

[KIDS PLAYING]

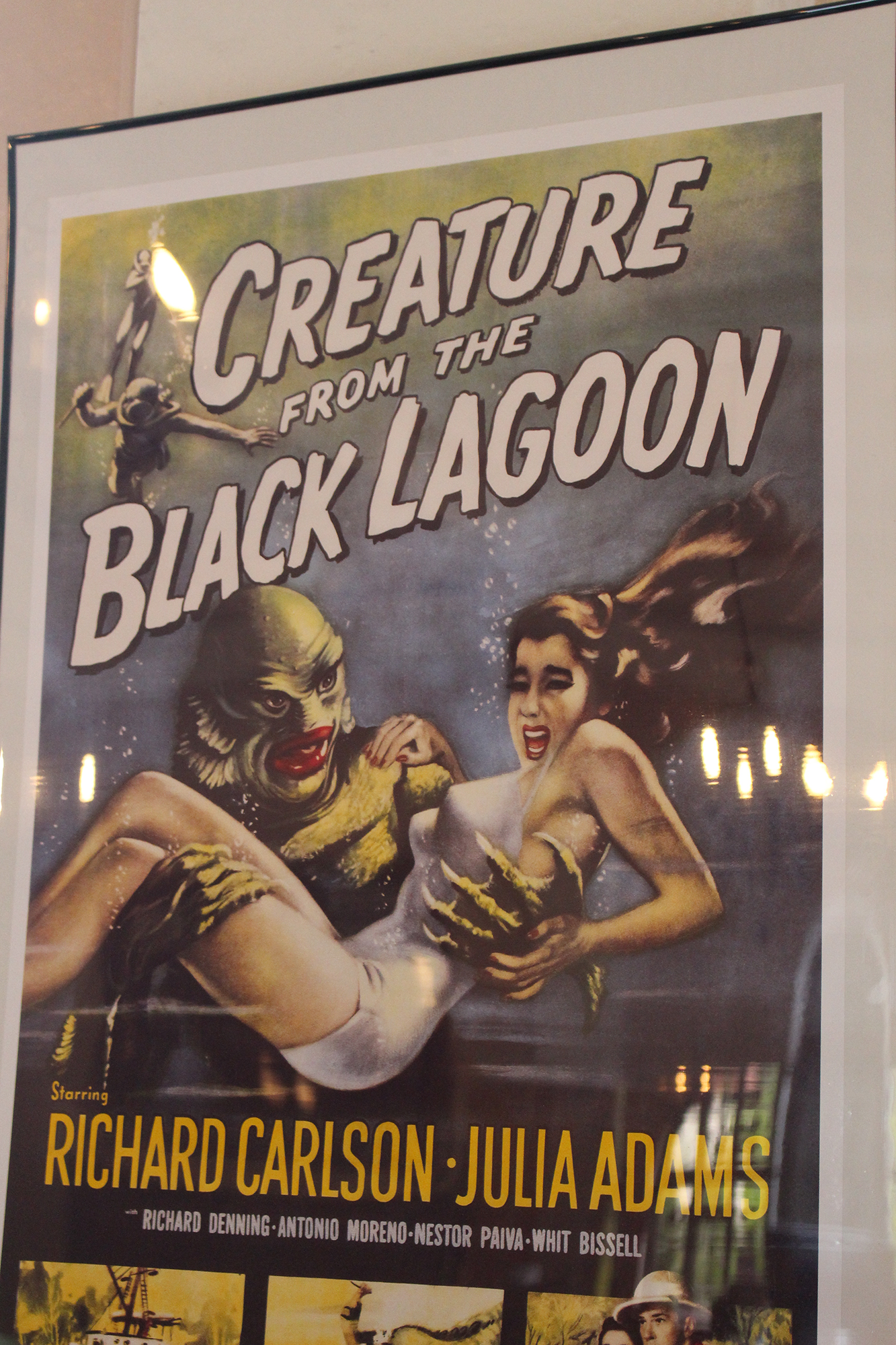

STRUCK: My childhood swimming hole was a mystical place. It was home of the Creature from the Black Lagoon‚ and Joe Panther and Tarzan. It was a movie stand-in for the Bermuda Triangle‚ - think Jack Lemon trapped in a submerged jetliner staring out at a freshwater bass.

This was Wakulla Springs, Florida, a place with water so vodka-clear it drew filmmakers, tourists and locals. We used to say you could flip a dime overboard and watch it hit the bottom 120 feet down. Schools of catfish glided in ethereal space as tourists oohed-and-ahhed in glass-bottomed boats above.

Dan Pennington, an environmental planner in Tallahassee, has watched the growth of algae in the springs. (Photo: Doug Struck)

The water was so clear that when Old Joe, an 11-foot gator, left his sandbar a couple hundred feet across the spring and moseyed over to our side, we could all see him coming. We got out of the water until Old Joe left, presumably with a toothy grin of amusement at his sport.

Wakulla and other springs bubble up from Florida’s limestone aquifer in clear, goosebump cold, brilliance. Marjory Stoneman Douglas, the famed biographer of Florida’s wetlands, called the springs “pools of light.” The lights are dimming.

PENNINGTON: If you've watched this spring just since 1980 since I've been watching it, you have watched this carpet of algae move up into the system and begin to cover everything.

STRUCK: Dan Pennington is an environmental planner in Tallahassee.

PENNINGTON: Now you just find strings of algae kind of hooked to the dirt, hooked to the rocks that are on the bottom and just sort of hanging and flowing in the current.

“Old Joe” shared Wakulla Springs with swimmers until a poacher shot him. He is now stuffed and behind glass. A reward still stands for his murderer. (Photo: Doug Struck)

STRUCK: Algae not only coats the bottom, but grows in microscopic particles that float in the water, turning it from clear to green.

KNIGHT: My name’s Bob Knight, I’m the director of the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute, located in Gainesville, Florida. We have about 1000 natural springs in Florida, artesian springs, and they are across-the-board suffering from reduced water volume flow rates and they are across-the-board polluted with nitrate nitrogen.

STRUCK: We talked as we hiked into Three Sisters Springs near Crystal River Florida. It’s a small fresh pool alive with swimmers on a hot summer day.

KNIGHT: But that right there is a spring boil area, that is where the water… (fades out).

STRUCK: The problem is too many people, who draw water for everything from drinking to watering lawns to irrigating fields from the same aquifers that feed the springs. And as the aquifers drop, the humans add more nutrients from fertilizer and sewage. Jim Stevenson was chief naturalist at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

Director of the Florida Springs Institute Bob Knight says all of the state’s springs are suffering. (Photo: Doug Struck)

STEVENSON: Springs die of two human acts. One is overpumping the aquifer that feeds the spring. And the other is putting nitrates into the aquifer and the source of nitrates are we human beings in the form of fertilizers, whether it's on golf courses, or lawns or crops. And also human waste as well as livestock waste.

STRUCK: To help reduce the nitrates in Wakulla Springs, the city of Tallahassee spent more than a quarter billion dollars on an advanced wastewater treatment plan. That’s helped, but there still are thousands of homes with septic fields in the watershed of the springs. The nutrients from these septic fields drain quickly through the sandy soil, into the aquifers, and out into the springs, where they feed the algae.

Former Florida Department of Environmental Protection official Jim Stevenson says over-pumping and too many nutrients are killing the springs. (Photo: Doug Struck)

STEVENSON: When you put water and sunlight and nutrients together, something green is going to grow.

STRUCK: The visibility has been cut so much, Wakulla is down to one glass-bottom boat. It’s taken out so seldomly that a moorhen ‚ a red-billed waterbird, has made a nest in it. Now, many of the 200,000 visitors to Wakulla Springs take the Jungle River Boat Cruise, and they still see lots of wildlife.

TOUR BOAT RANGER JEFF HUGIO: Yup. Looks like we’ve got a gator in the water up here on the right.

Crowd: Ooohhhh.

Hugio: He’s big.

Man: Oh, that’s a good one, too.

STRUCK: Years ago, there was a 33-foot diving platform. You had to get up your nerve, race up the steps and run straight off the edge. If you stopped to look down, you’d never jump.

But once in, you could snorkel down, down into a pool of wavy eel grass and gar and bass and turtles. You were amid the fish; they teased you, just out of reach. A dozen feet down was a hollow log that the bravest of swimmers would go through. Even braver scuba divers entered the labyrinth of caves that fed Wakulla. Some never emerged. Bob Thompson was a park ranger at Wakulla Springs for 11 years, and ran the tour boats.

Wakulla Springs Florida was Struck’s childhood swimming hole. Now the springs are less vibrant and clear than they were when he was young. (Photo: Doug Struck)

THOMPSON: So you start the boat dock and you build some interest as you proceed towards Wakulla spring‚ and it's a drop off from 23 feet to 120 feet deep. People just go crazy when they see that, you know Gasp! And Ooh my God‚ people who have a fear of heights are quite a bit scared generally.

STRUCK: The grass‚ and the log‚ are gone. The diving platform was cut down to a mere 20 feet. And Old Joe? He was shot by a poacher, although he is not entirely gone. He was stuffed, and now watches from a glass display in the lobby of the Wakulla Springs Hotel.

Bob Thompson retired, but went back to running the tour boats for awhile as a volunteer. Now, he has stopped.

Several movies, including “Creature from the Black Lagoon” were shot at Wakulla Springs because of the brilliant clarity of the water. (Photo: Doug Struck)

THOMPSON: I un-volunteered from driving river boat tours and I wish that it weren't so, but more and more, I see what is missing. I have this vision in my eye of crystal clear, air clear water, and now the water’s green or brown, and dark. It makes me sad.

STRUCK: Well, to see for myself, I came back to Wakulla spring‚ it had been a few decades‚ and I took the plunge.

[SPLASH]

STRUCK: Just as cold as it always was. Now to see what I can see underwater. It’s disappointing. The algae is a black fuzz that coats the bottom and sucks up all the light. The luxurious waving eel grass is pretty patchy, the schools of fish are mostly missing. The Wakulla Springs of my childhood swimming hole, the Wakulla Springs of jeweled luminescence, now exists only in memories.

This is Doug Struck at Wakulla Springs, Florida, for Living on Earth.

Links

Florida's Vanishing Springs - Tampa Bay Times

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth