Beyond the Headlines

Air Date: Week of August 21, 2015

While attempting to clean contaminated water at the Golden King Mine in Colorado on August 5th, workers accidentally caused an enormous leak. The spill released 3 million gallons of mining waste into the Animas River, turning the water orange and increasing lead concentrations to 12,000 times the normal level. (Photo: River Hugger, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra reminds host Steve Curwood that despite the recent EPA-induced mine waste spill on the Animas River, larger spills from abandoned mines contaminate the nation’s rivers daily. And on the eve of the anniversary of Katrina, Dykstra remarks that more people are moving into harm’s way, and looking back into environmental history, notes how unwise it is to mix steeples, lightning and ammunition.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Let’s head off beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. He’s part of the team at Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org, and joins us on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hello, Steve. Y’know over the past couple weeks I’ve been pondering the spectacle out in the Animas River, much in the news because an EPA cleanup contractor poked a hole in the waste lagoon from the abandoned Gold King mine, and three million gallons of liquid mining waste turned the river into a grotesque mustard yellow color for a few days, shutting the river to recreation and prompting drinking water concerns in Colorado, Utah, and the Navajo Nation in New Mexico.

CURWOOD: Yeah, the images of a bright yellow river in the desert were, well, shall we say‚ memorable?

With climate change, raising sea levels and worsening storms, growing coastal populations may be in trouble. (Photo: Maf04, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Right, and EPA and other regulatory agencies are already pretty unpopular, particularly in the West, but a strange thing happened in the political blowback to all of this. Frequent EPA critics who otherwise wouldn’t know mines from a hole in the ground got really, really worked up over mine waste, now that EPA is responsible for a spill. A three million gallon spill is not good. But as you reported last week at Mount Polley, an active gold and copper mine in British Columbia last year, a dam broke sending about five billion, with a B, gallons of waste downstream. In the western US, there are thousands of abandoned hard rock mines like the one EPA was trying to clean up. And all over the country, there are coal ash dumps like the one in Tennessee that dumped a billion gallons of toxic waste into the Emory River nearly seven years ago, or a similar spill in the Dan River in North Carolina last year.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and not just the coal ash dumps at power plants, but abandoned coal mines as well, right?

DYKSTRA: Absolutely and after the Animas River spill, the newspaper in Scranton, Pennsylvania reminded its readers that abandoned coalmines in the area spill more acidic, metal-contaminated waste into local rivers every day than EPA’s gold mine accident did. In terms of staffing, budget, and political clout, EPA is in way over its head in inspecting and trying to fix mine waste hazards. Many state agencies are in an even worse position.

CURWOOD: Overwhelmed and underfunded, huh? What other cheer do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: There’s much talk about big storms, what with Katrina’s tenth anniversary coming up on August 28th. Like mine waste, it’s a big problem, and our response doesn’t necessarily match up. We’ve been lucky for the past decade on the U.S. East Coast with Tropical Hurricanes, even though Superstorm Sandy kicked New York and New Jersey through the goalposts. And the East Coast’s luck isn’t universal: Typhoons have taken a huge toll in Asia in recent years. But our luck may be our last refuge. Hurricanes may have been sparse, but they’re by no means gone. Sea level rise will make the storm surges worse, and there are far more people living along the coast, taking a big gamble. There were 600,000 people in Lee County, Florida‚ that’s where Fort Myers is - in the last census. 100 years earlier, there were 6,000. A hundred times the increase in a hundred years. So for all the people in harm’s way, let’s make sure we do more than just remember Katrina. Let’s make sure we’re getting ready for the next one.

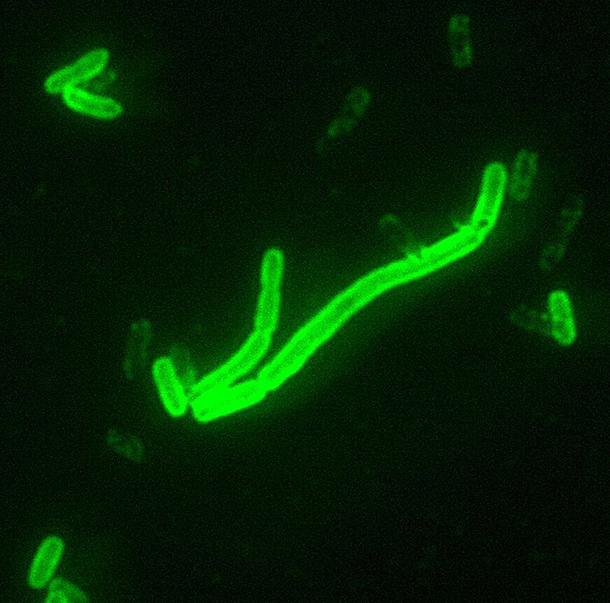

In the summer of 1630, ‘wise men’ investigated the plague-ridden streets of Florence in the world’s first public health survey. Some citizens thought vampires were to blame, but the culprit was actually the flea-borne bacterium Yersinia pestis. (Photo: CDC, public domain)

CURWOOD: So in addition to all this advice, Peter, it’s time for our history lesson. Take us back in time‚ what do you have on the calendar for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Two items about being prepared -- or not - from Italy a few centuries ago, and two reasons why we learn from history. In August, 1630, the city fathers of Florence were coping with the plague and they had a novel idea: a visitation, where wise men would comb the streets and alleys of the city to figure out what was causing the epidemic. It may have been the first public health survey in history, though many Florentine citizens remained convinced that vampires caused the plague, not flea-carrying rats as we know today.

CURWOOD: And what else?

DYKSTRA: The year 1769, the northern Italian city of Brescia, which is about midway between Milan and Venice. This is back in the day when the church is the center of everything in a community, so city leaders thought it would be a dandy place to store all the gunpowder. Beneath the steeple. That didn’t have a lightning rod, which had just been invented a few years earlier. Roughly three thousand people died and one-sixth of the city was leveled by the deadliest lightning strike up until that time in history.

In the olden days, lightning storms sometimes carried an extra dose of deadliness. Poor decisions to store gunpowder beneath church steeples resulted in the deaths of several thousand people in eighteenth century Brescia and nineteenth century Spain. Modern cities opt for lightning rods and safer explosive storage. (Photo: JP Marquis, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: So there’s been a worse lightning disaster since then?

DYKSTRA: Yes, 4,000 lives were lost in 1856 on the Greek Isle of Rhodes when lightning hit a church steeple above vaults full of gunpowder and explosives. So Steve, please check the lightning rod on the Living On Earth castle.

CURWOOD: Will do. And we’ll keep our powder safe and dry and elsewhere. Peter Dykstra’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks for taking the time today, we’ll talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth