Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner and the American West

Air Date: Week of August 21, 2015

Edward Abbey’s incendiary novel The Monkey Wrench Gang involves a plot to blow up the Glen Canyon Dam, pictured above. Wallace Stegner, who also opposed dams on the Colorado River, compiled the book This is Dinosaur to help stop a dam that would have flooded Dinosaur National Monument. (Photo: AL_HikesAZ, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

Author David Gessner discusses with host Steve Curwood the legacies of the two writers he explores in his new book, All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West. Abbey’s fiery, pugnacious attitude towards wilderness preservation departed vastly from Stegner’s more mild-mannered, eloquent persuasion on the cause, yet both Abbey and Stegner were true writers of the Western landscape.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Among the writers inspired by the American West, two of the most iconic are Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner. When Abbey wrote the novel The Monkey Wrench Gang he seeded a new brand of radical environmentalism‚ maybe even eco-terrorism, while Stegner’s prose promoted the passage of the Wilderness Act. Now, a writer of our own time has traveled across the West and through the pages of their books to discover their legacy and relevance today. David Gessner’s new book is called "All The Wild that Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West", and he joins us now from Boulder, Colorado. David, welcome to Living on Earth.

GESSNER: Thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: Tell me about these two writers, Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner. Why did you decide to write about them in particular?

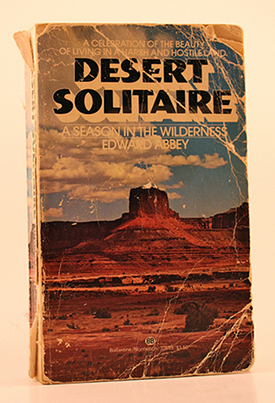

Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, a memoir of sorts, introduced scores of readers to the somewhat-fictionalized character of Ed Abbey himself and popularized Arches National Park as “Abbey’s country.” (Photo: Frank Smith, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

GESSNER: Well I moved west from the beautiful city of Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1991. I'd gone through a rough period that included testicular cancer, and I applied to five graduate schools in creative writing, and I was rejected by four. The one I got into was Boulder, Colorado, and it changed my life. I was kind of airlifted from Worcester to Boulder, and as I moved west, I started to read the west, and I started with "Desert Solitaire" which is a book that has converted many a person at Abby's great kind of modern Walden, and I was kind of coming back to life and it was exhilarating reading.

Abbey proved a gateway drug to Stegner and I love the two guys, and I said, "I'm going to live in the west forever." It turned out forever lasted seven years.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

GESSNER: And I took them with me when I came back east. So I moved back to Cape Cod. Suddenly I was looking at my old land in a new way. I think I just always wanted to get back to them, and three summers ago I headed west to kind of followed their trails and threaded in biography as I went.

CURWOOD: In a way, Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner were both immigrants to America's west, kind of like you. I imagine that's part of the attraction.

GESSNER: It really was, particularly with Edward Abbey. He was born in Indiana, Pennsylvania, which is really kind of the Appalachians and he had always dreamed and fantasized about the west, had little cowboy pictures, and at 17 he hitchhiked west. And that first moment of seeing the mountains totally changed his life. He, in typical Abbey fashion, compared it to seeing a naked girl. He said it struck a fundamental chord in his imagination that has rung ever since. And I think a lot of us who made that same drive know that feeling.

Stegner’s famous “Wilderness Letter” on the importance of federal protection of wild places was used to introduce the Wilderness Act, which President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law on September 3rd, 1964. (Photo: Jerchel, Wikimedia Commons)

When I did it driving from Worchester, I remember I wrote in the book, “Had John Denver himself come on the radio I would have warbled along.” So that was kind of Abbey's newcomer take. Stegner’s was a little different. Though he was born in Iowa and spent his earlier years in the Dakotas. Then his dad who was this typical frontiersman migrant moved them to Washington State, then up to Saskatchewan then to Montana and Salt Lake City. So we was always in movement. Stegner, with his large mind, kind of extrapolated from that early movement and saw that as a typical western way of being, going to a place, trying to take from it and moving on. So they were different sorts of westerners, but they both were always in movement.

CURWOOD: Now how did these two writers respond to each other’s work? I gather they crossed paths at Stanford at one point.

GESSNER: They did. Well, the way they responded to each other was a little different than the way they responded to each other's work. I looked all over through Abbey's journals. You know, Stegner was his teacher for a year at Stanford. He wrote everything down in these journals. And the only thing I could find Abbey saying about Stegner was, “He had the most distinguished looking bags under his eyes.”

CURWOOD: (LAUGHS)

Since the Wilderness Act became law in 1964, 109.5 million acres have been designated as wilderness, amounting to 5% of the total land in the United States. The John Muir Wilderness, which includes Marie Lake, shown above, stretches for 100 miles along the crest of California’s Sierra Range. (Photo: Steve Dunleavy, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

GESSNER: So they didn't make much of an impression, strangely. You know, Abbey was just the kind of guy that by the 1960s Stegner would have disliked. Stegner said he didn't like writing that throbbed rather than thought. He didn't like Ken Kesey, for instance. Kesey said of Stegner, “He drank Jack Daniels and I took LSD.” And he didn't like hippies, and Abbey had a kind of hippie side to them, or at least a wild side. But what they had in common was the place itself. So in Stegner's mind that's what rescued at Ed Abbey as a writer, and Abbey said of Stegner that he had an excess of moderation. That was his complaint with Stegner.

CURWOOD: So compare their writing styles for me.

GESSNER: You know, a couple of people along the way said Stegner’s was more academic. I don't find it academic. Both men, through some of their books were nonfiction, their essential goals early on were to write the Great American novel, to be Hemingway, to be Thomas Wolfe, to score the big one. And the fiction writing of Stegner to me carries over into his nonfiction. It's smart, the later books have what I call the “grumpy grandpa” narrator where it's kind of this first person curmudgeonly sharp-tongued kind of writing. Abbey really found his voice when he turned to nonfiction. An editor in New York suggested, “why you right about that time you spent being a ranger in Canyonlands,” and he wrote it and it's amazing the way the voice comes through on the page.

Abbey grew up in the small town of Home, Pennsylvania, but always dreamed of heading west. At seventeen, he hitchhiked there and found a place that truly resonated with him. (Photo: Tillman, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Now, my take is that both of these men were actually pretty angry about what was going on in the west and some aspects of their own lives, and yet they had, well, rather different styles of expressing them.

GESSNER: Yeah, Stegner, whose, probably his most distilled example of that feeling was the Wilderness Letter, and he was quite upset. You k now, he'd been around for a while and was born in 1909 and he'd seen places that he loved be destroyed. But restraint was one of his watchwords and he talks in that Wilderness Letter about the west still being a place of hope. Later on in his life he started to feel some despair and he was the one who first said that we fight environmental fights, we have to keep winning them over and over and if we lose them once all is lost.

Abbey on the other hand was more directly pissed off about what was going on and he let people know. He said his writing grew from two places: love and hate. Places he had fallen madly in love with in the American West, in the desert, and he saw them despoiled, he didn't waste for words and he didn't spare words and he came blasting back at people. He compared to the philosophy of growth to the ideology of the cancer cell that kept growing and growing and killing its host. So, you know, Stegner, with his excess of moderation, may have rolled his eyes a little about Abbey, but Abbey was effective. I've never heard of a writer, I've never seen a writer, who has such direct literary influence.

CURWOOD: So in what ways has the environmental movement had to adapt to the recasting of the Monkey Wrencher that Abbey was talking about as ecoterrorist and the FBI...you know goes after folks who try to sabotage infrastructure and development.

Stegner grew up west of the Rockies but only began to recognize how much the place had shaped him when he left it to attend college at the University of Iowa. (Photo: Bede735, Wikimedia Commons)

GESSNER: Well, I spoke to an FBI agent, Jane Quimby, she's a retired FBI agent, and I said what would a young imaginative Monkey Wrencher now? She kind of looked at me like I was crazy, as if she was saying you realize I'm an FBI agent right? But then we worked our way around to things like whale wars or Tim deChristopher who bid on oil land, in the waning days of the Bush Administration, and took it out of the oil companies’ hands, and landed in jail for two years in Denver. And even though that might not have done much practically, it’s the power of symbol that I think we still take from Ed Abbey. You know, Earth First unfurled the crack in the Glen Canyon dam, just a drawing of the crack, a depiction of it, and that too is the power of symbol. So Ed wouldn't do very well today, he’d probably end up in jail, I mean he shares some rough borders with the Unabomber. But what I think is still viable now is his strength and his power of symbol.

CURWOOD: So to what extent do you think Abbey and Stegner intended their writings to encourage activism?

GESSNER: Well, it's an interesting thing. Both said clearly that making great literature was their number one goal. Number two...like Stegner actually wrote it out with a one and a two, was saving wildlands and fighting for the environment. And in that regard Stegner did not mind being openly propagandistic, he didn't mind turning his ability to use words toward the fight, but he would've frowned on anyone looking at his novels and seeing that same thing there. Abbey's a little different because in a way “Monkey Wrench Gang” is kind of like "Uncle Tom's Cabin" or any overtly political book. He makes no bones about the fact that this wacky band of people is going around with dreams of blowing up the Glen Canyon dam. Abbey saw in his own lifetime that Earth First started because of his books and many other direct outcroppings of his work.

Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang fomented environmental radicalism beginning in the 1970s. Earth First! activists bar entrance to Pacific Lumber Company’s land in anticipation of logging activity. (Photo: Mark Bult, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, there is a criticism that wilderness is only accessible and relevant to a select group of people, making it elitist. In fact, folks like John Muir wanted the Native Americans off of wilderness land back when he was touting wilderness. How do you respond to that, and how would Abbey and Stegner respond, do you think?

GESSNER: Well, I think Abbey would respond in a very similar fashion to Stegner but with an angrier growl. The gist would be basically: this is a huge part of the best of what America has to offer, that we have these places where people aren't. And as Stegner said in the Wilderness Letter, there's something that's essential to the American character in having these wild places. And this might sound a little high falutin’, but having spent the last month traveling around the west, I've got to say, there's a psychological and mental correspondence between being in these places and just this physical lift. There's a greatness to it, and if we give this away we give away something essential, and the fight for it was at the core of the similarity between these two men. They weren’t looking to expunge these places of people, in fact, people interacting with these places was a thrill for Stegner.

The two writers crossed paths when Stegner taught Abbey in his creative writing course at Stanford in 1957, but they apparently did not make much of an impression on each other at the time. (Photo: David Schexnaydre, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, both Wallace Stegner and Ed Abbey lived in a land that's loaded with myth, you know, the rugged individual cowboy. How did they respond to that?

GESSNER: Well, Stegner wanted to pull the veil away. He hated the rugged individualist myth. He thought it was a lie. He saw the west as a place, because it was so dry and vast, that can only be settled by sharing, and his dad was the cowboy, so he reacted against that kind of cliché. Abbey's a little different. Abbey didn't like cows, he didn't like cows on public land and he made fun of cowboys. He almost got in a shooting match during one talk in Montana, but he was wearing those cowboy boots and he was out in the desert. In a way, Abbey used the cowboy myth to fight against the cowboy. He was a rugged individualist, but he understood that rugged individualism would ultimately kill the west.

CURWOOD: So how was it that these men are relevant today? We have climate change, we have wilderness on fire, we have drilling and mining and extracting. How do they speak to today's conditions?

GESSNER: I think Abbey does directly through the use of strong language and through the use of symbol. He kind of rousts us from our slumbers. I do worry that his voice, because it's so adamant, would just be added to the noise of the kind of MSNBC versus Fox constant clutter, but I think he could cut through and one reason I think he could come through is humor. You don't get a lot of that in environmentalism and he was a very funny man.

David Gessner is the author of Return of the Osprey, My Green Manifesto, The Tarball Chronicles, and other books. (Photo: courtesy of David Gessner)

Stegner tackles things as usual in a larger way. He was a master of connecting the dots. In his time, the dots in the west meant aridity, the cycles of drought, the importance of snowpack, and 50 years ago he was seeing things that are relevant to this summer in California and throughout the west. And he realized for instance that rain and snow are very different. Snowpack acts as a kind of a time release, letting water go through the summer, through the spring, whereas rain just rolls off the dry western land. So his brilliant big picture thinking would now have to include climate change, obviously, and it would also have to include loss of trees through beetles. And I've actually been singing as I've been traveling, if you remember the beginning of "All in the Family" where Edith and Archie sing, "Mister, we could use a man like Herbert Hoover again." I've been singing, "We could use a man like Wallace Stegner again." He's that kind of big thinker, he's really not just an American type but a western type.

CURWOOD: David Gessner is the author of "All The Wild that Remains" and eight other books, including "The Return of the Osprey" and "My Green Manifesto". Dave, thanks for joining us today.

GESSNER: Thank you very much, Steve.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth