Rethinking Our Relationship to Palm Oil

Air Date: Week of September 4, 2015

Palm oil is harvested from Elaeis guineensis, an oil palm tree native to Africa that is grown in Southeast Asia. The oil itself isn’t so bad—it has a much higher yield than other oilseed crops like rapeseed, coconut, and soya, so it requires less land to produce the same amount of oil. (Photo: Llan Pin Koh, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Palm oil production has long contributed to climate change by fostering rainforest and peatland clearance in Southeast Asia. But new solutions to the problems are on the rise. Living on Earth’s Shannon Kelleher investigates alternative oils that might come to share palm oil’s market niche and how processors are being encouraged to use more sustainable sources of palm oil.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Now one of the ingredients General Mills plans to source sustainably is palm oil. You’ll find palm oil in many products – but it has an unsavory reputation as an environmental villain. For the sake of peanut butter and packaged cookies, palm oil extraction is pushing endangered species towards extinction and making a hefty contribution to the world’s carbon dioxide emissions. But while the situation can look bleak for dwindling rainforests and endangered wildlife, thanks to new developments, and new thinking, there may still be hope for reform. Living on Earth’s Shannon Kelleher has our story.

KELLEHER: If you head towards the processed foods next time you go to the grocery store, odds are you’ll end up adding a dash of controversy to your cart. Whether the label says “palmitate,” “palmitic acid,” or just plain old “palm oil,” it all comes from the clusters of brilliant orange fruit of a tree called Elaeis guineensis with a big behind-the-scenes presence in our daily lives.

Between one third and one half of processed foods on supermarket shelves in the U.S. contain palm oil or an ingredient derived from it, including popular brands of peanut butter. It can be difficult to determine whether a product contains palm oil since it can go by many different names, including “palmitate” and “palmitic acid.” (Photo: Anthony Albright, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

BOUCHER: It has been estimated if you go into a grocery store and look at all the products on the shelves that a third to a half of them will have some palm oil in it.

KELLEHER: That’s Doug Boucher, the Director of the Tropical Forest and Climate Initiative for the Union of Concerned Scientists. He says palm oil is so abundant on the consumer market because it’s cheap and versatile. It works as a preservative in processed foods and has chemical properties that help products lather and thicken.

BOUCHER: It’s a vegetable oil for cooking, frying for example, but also for baked goods of many kinds, various beverages, cosmetics, personal care products, soaps, shampoos…

KELLEHER: But before it comes anywhere near your grocery cart, about 85% of all palm oil is harvested from plantations in Malaysia and Indonesia. Between 1990 and 2010 an area of forest almost as big as 2 million football fields was cleared to make way for oil palms, helping drive endangered wildlife like orangutans and Sumatran tigers even closer to extinction. The clear-cutting continues today and Doug Boucher says that poses some uniquely sinister threats.

BOUCHER: Substantial areas of Southeast Asia have very carbon-rich soils, peat soils, with sometimes quite thick deposits of peat.

Between 1990 and 2010, the land equivalent of almost 2 million football fields was cleared to plant oil palm trees in Southeast Asia. By 2020, carbon emissions from burning forests are estimated to be over 558 million metric tons. (Photo: Achmad Rabin Taim, Wikimedia CC BY 2.0)

KELLEHER: As the peat is drained for oil palms, large amounts of carbon dioxide are released. And the peat can burn, releasing three to four times as much carbon as rainforest clear-cutting. These problems have caused some to seek out substitutes for palm oil.

JOHNSON: We use microalgae that grow in the dark.

KELLEHER: Jill Kauffman Johnson is the Global Sustainability Director for Solazyme, a company in California that uses microalgae to produce an oil for personal care products in very much the way other companies brew beer.

JOHNSON: We feed sugar, and the algae, and then put that all into a large fermentation tank. The algae then convert the sugar into oil, and it allows us to produce large amounts of oil in a matter of days.

KELLEHER: The technique is so productive that Solazyme has a contract to supply Unilever with 3 million gallons of algae oil for its soaps and other toiletries, as the multi-national company works to go greener and sustainably source all its raw agricultural materials in the next 5 years.

JOHNSON: We’re also finding in a recent study that we’ve had done that has been third-party reviewed, the greenhouse gas emission profile with the algae oil produced at our plant based in Brazil, where the sugar source is sugarcane, has a lower carbon footprint than that of palm oil and palm kernel oil.

Clear-cutting for palm oil plantations has destroyed a substantial proportion of orangutan habitat, and this practice is pushing endangered orangutans to the brink of extinction. According to the World Wildlife Fund, scientists believe there are now less than 60,000 orangutans left in the forests of Borneo and Sumatra. (Photo: Robert Paul Young, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

KELLEHER: The study shows that algae oil production emits about half as much greenhouse gases as palm oil production, and requires seven times less water. Even if you account for growing the sugar cane, yields are about the same as palm oil—some 3 and a half tons per acre of land. But algae isn’t the only alternative. Scientists at the University of Bath in the UK are developing an oil from a type of yeast, which can be found almost anywhere and can grow on almost any feedstock. So given palm oil’s drawbacks and the potential alternatives, it might seem like we should just scrap the stuff altogether. But Doug Boucher of the Union of Concerned Scientists doesn’t think so.

BOUCHER: It’s not that the crop itself is intrinsically evil

KELLEHER: In fact, it has a considerably higher yield than other oilseed crops such as coconut, rapeseed, or soy. Plus, an oil palm is a tree—and there’s a benefit to that.

BOUCHER: It actually accumulates carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in the process of growing, and that’s different from most crops. So if you produce it in areas that are not forested but rather you use already-cleared land, you can actually have a positive benefit from it.

KELLEHER: In hopes of even more positive benefits from the crop and less destruction, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, RSPO, was created in 2004. Palm oil producers can join the RSPO to have their product certified as “sustainable.” But Boucher says its regulations are voluntary, and far from perfect.

BOUCHER: That system doesn’t require them to stop deforesting, nor does it prevent them from clearing peat. It puts certain areas of forest off limits, which is better than nothing, but it doesn’t lead to no deforestation or no peat clearing.

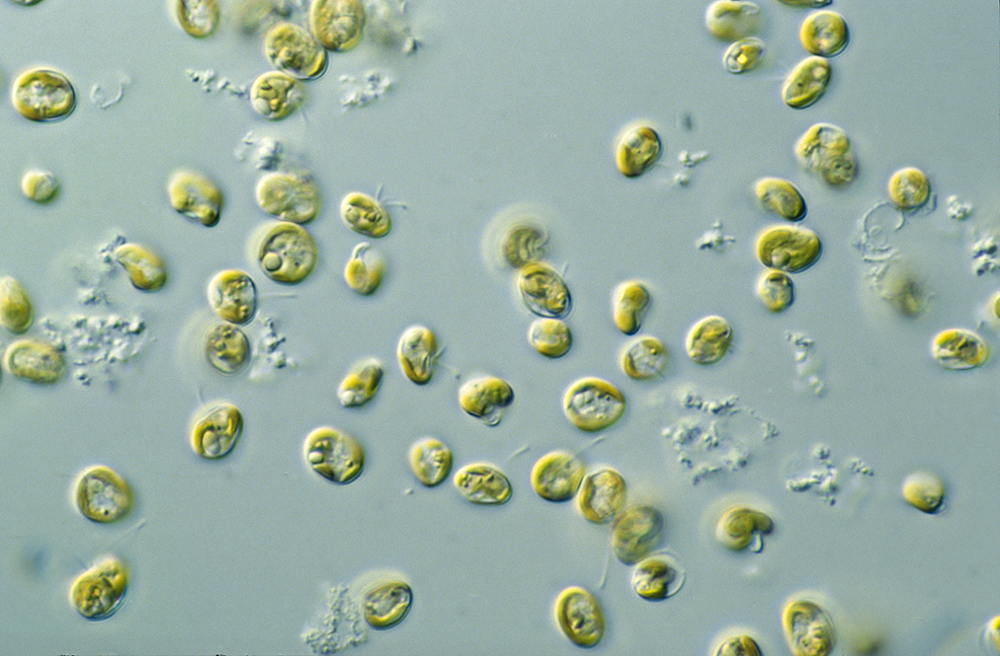

Solazyme, a company based in California, is using the fermentation abilities of microalgae to produce renewable oil similar to palm oil. It has a lower carbon footprint than palm oil and can be grown in fermentation tanks just about anywhere. (Photo: CSIRO, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0)

Kelleher: The Union of Concerned Scientists is pushing for change too by urging companies to commit to zero deforestation, holding them to their promises, and enforcing transparency about where they source their palm oil.

BOUCHER: Right now, for example, we have a campaign in relation to Starbucks, which is one of the ones that, despite its generally green reputation, in fact hasn’t made a zero deforestation commitment. And we’re asking them to.

KELLEHER: While not everyone is there yet, consumer pressure appears to be helping accomplish what the RSPO hasn’t, with major companies like Kellogg, Colgate–Palmolive, and Proctor and Gamble making zero deforestation commitments within the last few years. It seems there’s real power in turning an industry’s eye to the image its consumers see.

Doug Boucher is the Director of the Tropical Forest and Climate Initiative for the Union of Concerned Scientists. (Photo: Union of Concerned Scientists)

BOUCHER: You know, very often that when we hear something bad about a particular product, in this case palm oil, the initial thinking is ‘well I’ll just stop buying that entirely.’ And I understand that impulse, but in fact making companies produce that sustainably is actually better than simply giving up on it. It is better to worry about it because then you can actually get things changed.

KELLEHER: With more consumers thinking about the consequences of their purchases and more companies listening to consumer voices, maybe palm oil and sustainable living don’t have to be mutually exclusive. And Jill Kauffman Johnson from Solazyme doesn’t think we need to pick just one sustainable path, either.

JOHNSON: When we think about a global population predicted to reach 9 billion people in 2050, we will need to find all kinds of ways and all kinds of materials to produce enough food and clothing and shelter with less resources. And these solutions are actually going to come from a variety of sources.

KELLEHER: Ultimately, it might be a winning combination of sustainable solutions that helps endangered wildlife, saves our relationship with the environment and feeds the appetite of our growing world. For Living on Earth, I’m Shannon Kelleher.

Links

NASA satellites show palm oil’s contribution to climate change

The RSPO’s regulations are imperfect

Union of Concerned Scientists calls upon companies to go deforestation-free

Solazyme has developed an oil from microalgae

The University of Bath is making a palm oil alternative from yeast

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth