Coral Bleaching On the Rise

Air Date: Week of October 16, 2015

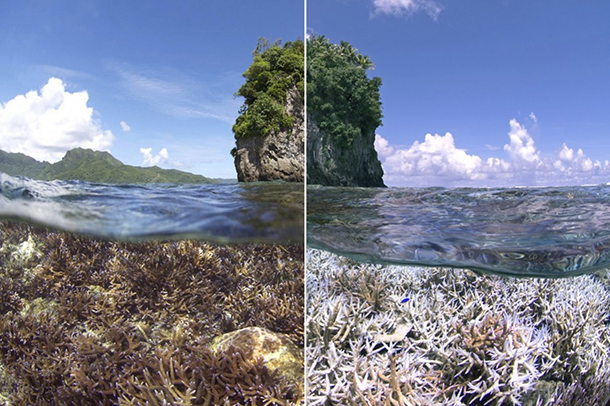

A before and after image of the bleaching in American Samoa. Images taken December 2014 and then February 2015 when the XL Catlin Seaview Survey responded to a NOAA coral bleaching alert. (Photo: XL Catlin Seaview Survey / Underwater Earth)

NOAA recently announced that corals around the world are undergoing severe stress and a die-off due to globally warming oceans. NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch program coordinator Mark Eakin describes how the current El Niño, climate change and a Pacific warm water “blob” combined are stressing corals and why bleaching events are likely to be worse in the future.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. The latest observations by NASA scientists indicate a strong El Niño has taken hold in the Pacific, and will affect rainfall, sea temperatures and storm activity into next year. Already, warmer water is adding pressure to one of the oceans’ most important and fragile habitats, coral reefs. Reefs are enchanting and beautiful, but also provide coastal protection from storms, and nurseries for fish. But now, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has announced that the world’s corals are turning a ghostly white, only the third such bleaching event on record. Mark Eakin is Coordinator for NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch program. Welcome!

EAKIN: Thank you, Steve, glad to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, what happens during a coral bleaching event?

EAKIN: Well, a coral is animal, vegetable and mineral. So, what happens in a coral bleaching event is that the animal part has microscopic algae living in its tissues, and the combination of those two builds the limestone skeleton that makes the massive coral reefs that they're known for. Well, when the temperature gets too high, the photosynthesis, the processes that make energy from sunlight in the algae, start to run too fast, and that releases toxins into the coral. And so the coral will eject the algae into the water so that robs the coral of the algae that gives them most of their food and gives them their color, and you can see right through to the white skeleton - and that's why it looks bleached. So the coral is still alive, but it's sick and it is starving.

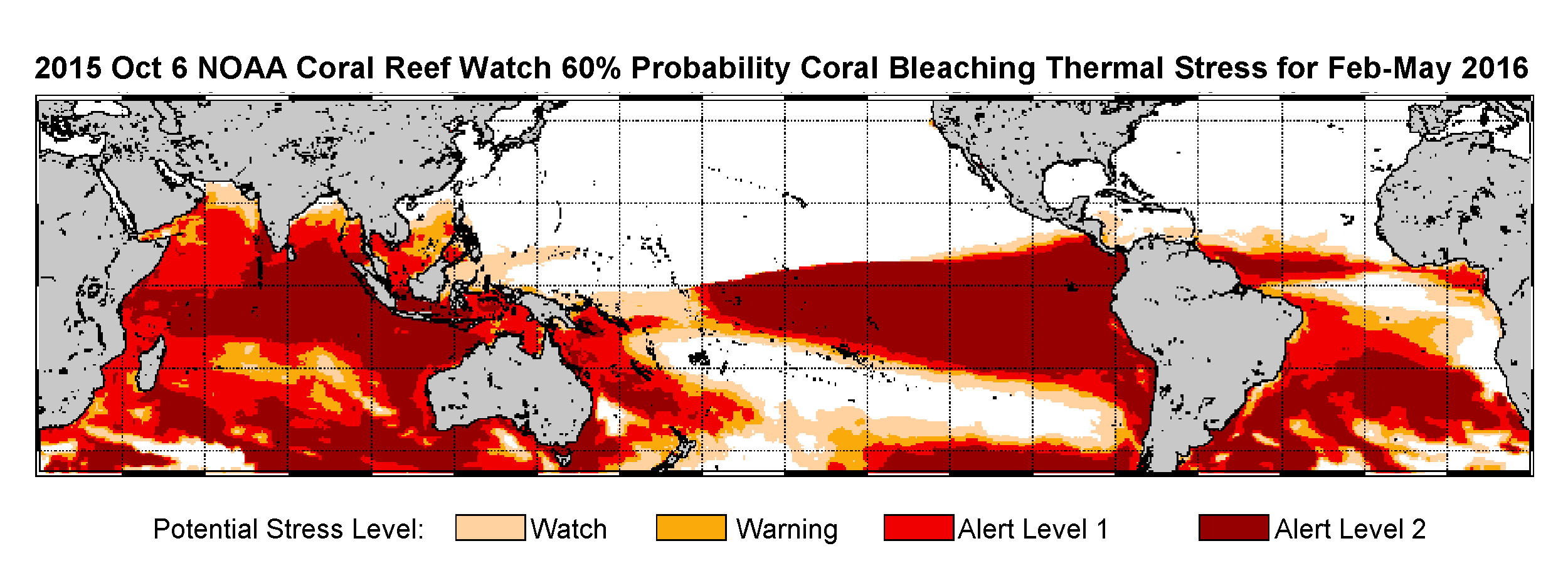

February-May 2016: An extended bleaching outlook showing the threat of bleaching expected in Kiribati, Galapagos Islands, the South Pacific, especially east of the dateline and perhaps affecting Polynesia, and most coral reef regions in the Indian Ocean. (Credit: NOAA)

CURWOOD: Now, we're in the middle of the third worldwide coral bleaching that modern science has recorded. When and where did it start and which reefs are most affected?

EAKIN: So this event actually started in June 2014 and we've had continuous bleaching of corals in various parts of the Pacific since that time. It started in the western north Pacific and the US territories of Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and while that was going on we started seeing bleaching in Hawaii, especially in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands, but even getting down into the main Hawaiian Islands. This is only the second time they've seen bleaching in the main Hawaiian Islands. From there, water started to warm in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, they saw the worst bleaching they've ever seen. It moved into the South Pacific and you were seeing the bleaching from the west over in the Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, down to the south in Fiji and to the east in the Samoas. Then we started seeing this El Nino kick in. Bleaching started across the Central Pacific in the islands of Kiribati, the Phoenix, Gilbert, and Line Islands, bleaching over in the Galapagos. After that we started seeing a normal cycle that leads to this global pattern where the atmosphere caused the Indian Ocean to start warming up. We saw bleaching in the Indian Ocean a little bit into Southeast Asia and the coral triangle, and then once we got around to the northern hemisphere, summer to fall, bleaching started in Florida, Cuba, and across the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

CURWOOD: So how much of coral around the world is likely to be affected by all of this and by the way where's the US in this picture?

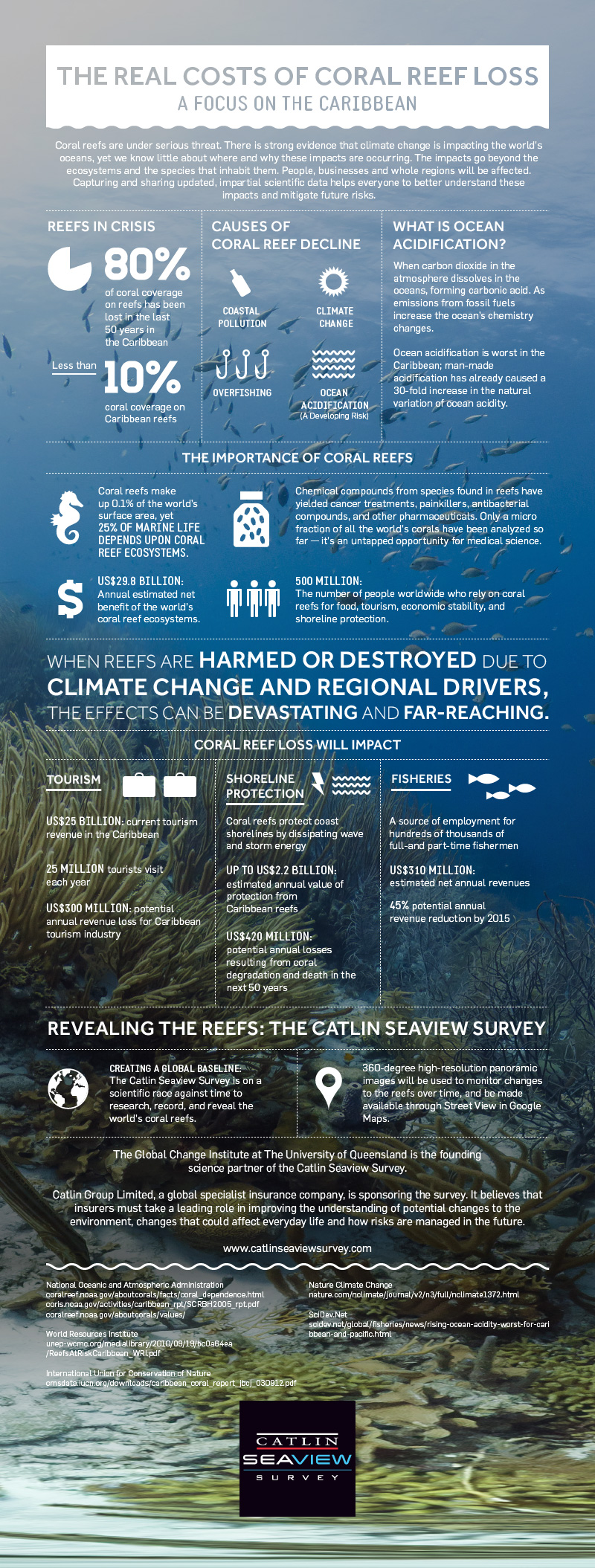

The real costs of coral reef loss (Photo: XL Catlin Seaview Survey / Underwater Earth)

EAKIN: About 38 percent probably will suffer this sort of prolonged high temperatures that cause bleaching by the end of this year globally. In the US it's actually going to be worse. We're looking at maybe as high as 95 percent, but unfortunately a lot of what we've been seeing this year was not driven by this strong El Nino right now, but by the warming that happened before that in 2014 and into early 2015. So as a result, our climate models show in 2016 the coral bleaching is likely to be even worse in some areas, and it looks like the warming in the Indian Ocean is going to be very extensive and much higher than what we saw this year.

CURWOOD: How much does water temperature have to increase for corals to get into trouble?

EAKIN: Yeah, that's the surprising thing for most people is that it's not that high. Really we usually see water temperatures of one to two and half degrees Celsius, so around one and a half to three or four degrees Fahrenheit at most above the warmest temperatures these corals normally see. Once you get past about one degrees Celsius, you are looking at enough stress that bleaching can start to kick in, and when that either goes higher or up toward 2, or when this is maintained which is usually the case of a prolonged event, that's when you start to see bleaching.

CURWOOD: To what extent can you connect the dot between all this coral bleaching around the world and climate disruption?

EAKIN: Well that's not a very long line that you have to draw. Climate change has been increasing the water temperatures very consistently over the last several decades and in fact the first bleaching events we saw were in '82, '83 with a huge El Nino maybe as big as '97, '98, but the bleaching was only in the Eastern Pacific and the Caribbean. Now we get up to ‘98, you've got a big event; it's on warmer water temperatures. You see a lot of bleaching. 2010, a moderate event, a lot of bleaching all around the world. The corals are already pushed near their limits to start with, and so doesn't take much to go on top of it. The problem we're seeing now is this event has been going on since mid-2014, and this year we’ve got the El Nino going on. We've also got this warm water mass in the northeastern Pacific called “the blob” and the two of those are conspiring with climate change to cause the bleaching that we're seeing right now in Hawaii. So we could be looking at an event that lasts at least two years, two and a half, uncertain how long.

CURWOOD: “The blob”? I'm mean, is this a bad Hollywood movie? What is “the blob”?

On the left, a healthy coral with its symbiotic algae. While the coral on the right is still living, it’s missing its algae, which help provide food to the coral. (Photo: NOAA, public domain)

EAKIN: The blob is a mass of warm water in the northeastern Pacific that has been around for about a year or so. It is somehow related to a variety of climates cycles like the Pacific decadal oscillation and the Arctic oscillation, it's probably related to climate change. There are other things that could be driving it, but to be honest, we don't really know quite what it is.

CURWOOD: How long does it take typically for reef to recover, at least start to recover, from an event like this?

EAKIN: Well, there really are two scales of recovery. First of all, when you have a bleaching event, it can take months for them to get those algae back, but when you're talking about a really severe event where the corals die, then it can take decades, and that's not even full recovery. These reefs may bounce back and look really good after 10, 15, 20 years, but all you're growing back at that point are the fast growing corals. You can't regrow a 200, 300, 400 year-old coral in 10 or 20 years.

CURWOOD: Mark Eakin is coordinator for NOAA's coral reef watch program. Mark, thanks so much for taking the time today.

EAKIN: Thank you very much, Steve.

Links

NOAA Coral Reef Watch: Bleaching Alert Area

NOAA declares third-ever global coral bleaching event

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth