The Creole Pig

Air Date: Week of October 23, 2015

Pig in Delmas, Port au Prince (Photo: Allison Griner)

In Haiti, the creole pig was a staple of the peasant economy, bringing families economic stability, devouring food waste and occasionally becoming an religious sacrifice. But as Allison Griner reports, disease killed many creole pigs and American efforts to control the swine flu took the rest. Efforts to replace the pig failed, but now peasant farmers are slowly rebuilding the creole pig herd.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Canada isn’t our only neighbor with an election; the Caribbean nation of Haiti chose October 25th to begin its round of polling. There are multiple parties contending and even preliminary results won’t be announced until November 3rd. Part of the delay is logistical. Haiti is largely rural and lacks much in the way of infrastructure to serve the many people who live on tiny farms scattered about the countryside. And as reporter Allison Griner found as she travelled the hilly central section of Haiti, agricultural life doesn’t rely on the cash economy.

[ROOSTER CROWING]

GRINER: As you ride through the Haiti's Central Plateau, you pass farm after farm, fenced in by neck-high cacti. Goats sidle by. Roosters crow. And occasionally, you'll see a fat, floppy-eared pig among them. But three decades ago, you might not have seen any pigs at all. That's because, in the late 1970s, a contagious, hemorrhagic disease called African Swine Fever had reached Haiti's shores. It had traveled from Europe to the Caribbean region, and its arrival in Haiti meant bad news for the nation's pig farmers.

CHAVANNES: [SPEAKING IN FRENCH, WITH TRANSLATION] In the Haitian peasantry, we consider the creole pig as the peasant's bank.

GRINER: That's Jean-Baptiste Chavannes, a candidate for the 2015 Haitian presidential election held on Oct 25. He rose to fame as a leader in the National Congress of Papaye Peasant Movement and a former recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize. Chavannes, who was born to a peasant family, says creole pigs were an important source of wealth to those with little else of value. Over 40 percent of Haiti's population lives in the countryside, where there are extremely high rates of poverty.

CHAVANNES: Why did we call the pigs banks? Because the peasant could keep his pig not far from the kitchen. And the pig would eat all sorts of trash. If I know that next year I'm going to send my son to high school, I will increase what I feed the pig so that I can sell it. It was a permanent source of security for the family.

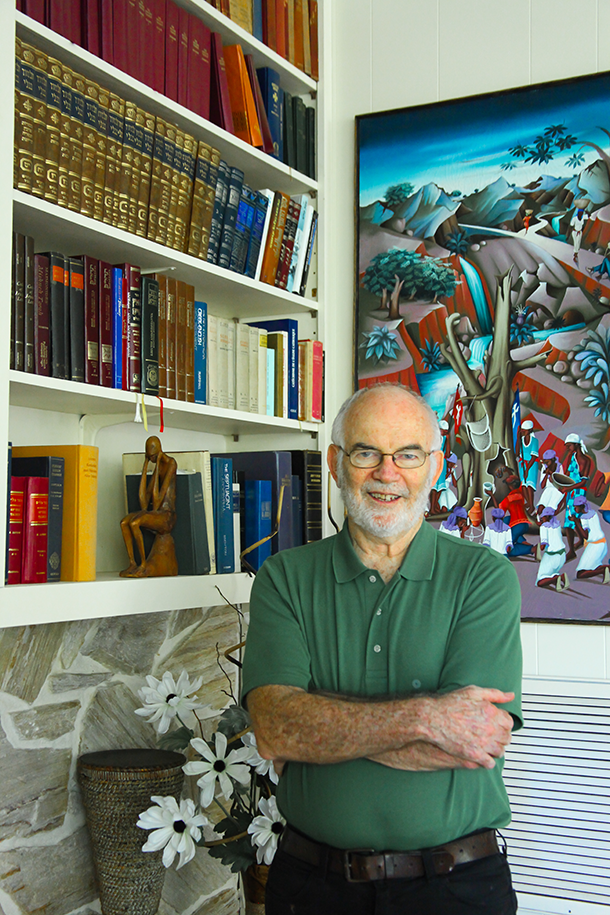

Jean-Baptiste Chavannes at Papaye Headquarters (Photo: Allison Griner)

GRINER: But the creole pig meant more than just money to the Haitian people. It had symbolic value, too. Gerald Murray, a retired anthropology professor from the University of Florida, did fieldwork in Haiti before the outbreak. He saw the creole pig play an important role in Haitian religion.

MURRAY: There's a folk religion that the Haitians called “sevi lwa”, serving the spirits. Outsiders call it Voudou. Part of voudou ritual entails what religions around the world have done, which is animal sacrifice. Different spirits have different tastes. The pig was the preferred meat of the more violent of the spirits.

GRINER: But in the late 1970s and early '80s, these pigs, which represented such a significant chunk of Haitian history, were falling victim to swine fever.

CHAVANNES: Every peasant family was touched. Every one. Because every Haitian family had a pig.

GRINER: Something had to be done. So a coalition led by USAID-- the United States Agency for International Development-- came up with a controversial solution. They decided to exterminate the creole pig, to prevent the incurable disease from spreading. But that decision left many Haitians with unresolved questions, Murray says. Some grew suspicious of USAID's motives.

MURRAY: I mean, during the epidemic, there were dead pigs floating in the rivers. A lot of pigs were dying. But the meat was harmless to humans. So why do you kill all the pigs? Why not protect the healthy pigs? Why declare all pigs dangerous? And the answer is they're protecting the pigs in the United States. That's the common answer given.

GRINER: At the time, Chavannes was a rising star in Haiti's peasant movement. He and his colleagues tried to intervene and convince groups like USAID to stop the slaughter.

CHAVANNES: We tried to resist, but no. We had to completely eliminate the creole pig. Certain peasants hid some pigs anyway, but very few.

GRINER: The government tried to compensate farmers for their lost creole pigs, but the process was fraught with corruption and scams, according to Murray.

MURRAY: The only externally funded project I've seen the worked perfectly was the slaughter of the pigs. Very efficiently done. The repopulation? Not as efficiently done. Not as efficiently done.

Creole pigs wade through garbage and food waste in Haiti’s Delmas (Photo: Allison Griner)

GRINER: American pigs were brought in to replace the creole pig, but they were ill-suited to the hard conditions that the creole pig thrived in. Murray says farmers struggled to accommodate the new livestock, which had very particular and very expensive needs.

MURRAY: Poorer farmers could get a free pig, but they had to agree to take care of it in a certain way. They had to agree to build a certain type of pen for it, and not give it garbage. They had to give it good food. But the problem was, the food cost about 100 dollars a year. I mean, people made about 150 dollars, so the pig would be eating better than the people.

GRINER: The problems didn't end with the added expense. Chavannes observed that the new pigs were causing trouble for rural families.

CHAVANNES: Those pigs ate the chickens. They attacked children. And when we saw that, we said, this is impossible. Haitian families cannot raise these pigs. And so we started to really protest.

GRINER: Chavannes started to notice peasants turning to other sources of income. He says the extermination of the creole pig forced many peasants to harvest wood to make charcoal. That only exacerbated the problem of deforestation in Haiti. And it's a big problem too. Over 98 percent of Haiti's land has been sheared of its forests. Erosion and droughts have increased as a result.

CHAVANNES: It's catastrophic for the environment. Just like when a peasant wants to send his kids to school-- before he could sell a pig. Now that he has no more pigs, he cuts trees. There is a direct relationship between the impoverishment of peasant families and the cutting of trees to produce charcoal.

GRINER: To reverse the trend, Chavannes and his colleagues in the peasant movement decided to reintroduce the creole pig-- or at least a hybrid that could fill its place.

CHAVANNES: We want the return of the creole pig. So we led a fight, and over the years, the minister of agriculture finally started a program for the repopulation of the pigs. They brought sows from

GRINER: But just as the new pig herd was starting to grow, once again disease intervened. This time, the culprit was teschen, a virus that can kill a pig within days. Six years ago, it started to spread. And decades of work were lost.

Gerald Murray is a retired anthropology professor from the University of Florida, who had done fieldwork in Haiti before the outbreak. (Photo: Allison Griner)

CHAVANNES: That's why we converted our pig repopulation program to goat farming. It's easier to raise pigs. It's less dangerous for the environment, et cetera. But this is the new situation.

GRINER: Still, the fight is not yet over for the creole pig. Vaccines for teschen are already being tested in Haiti, and Chavannes hopes partnerships with international NGOs will help fight this latest disease. Part of Chavannes' mission is to rebuild the peasant economy. But to reach that goal, bringing back the creole pig is a necessity, he says.

CHAVANNES: We must. [Laughs] We must, and like I said, pig farming is indispensable for reestablishing the peasant economy. We must act rapidly against teschen to save the race. But I hope that we won't lose them all. That we will have the time to fix this problem.

GRINER: Already, the race to save Haiti's pigs is well underway. This past spring, an official from the ministry of agriculture announced that the 500,000 doses of the teschen vaccine had been produced. The official says they are currently available for farmers to use.

For Living on Earth, I'm Allison Griner.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth