Better Office Air Makes For Better Thinking

Air Date: Week of October 30, 2015

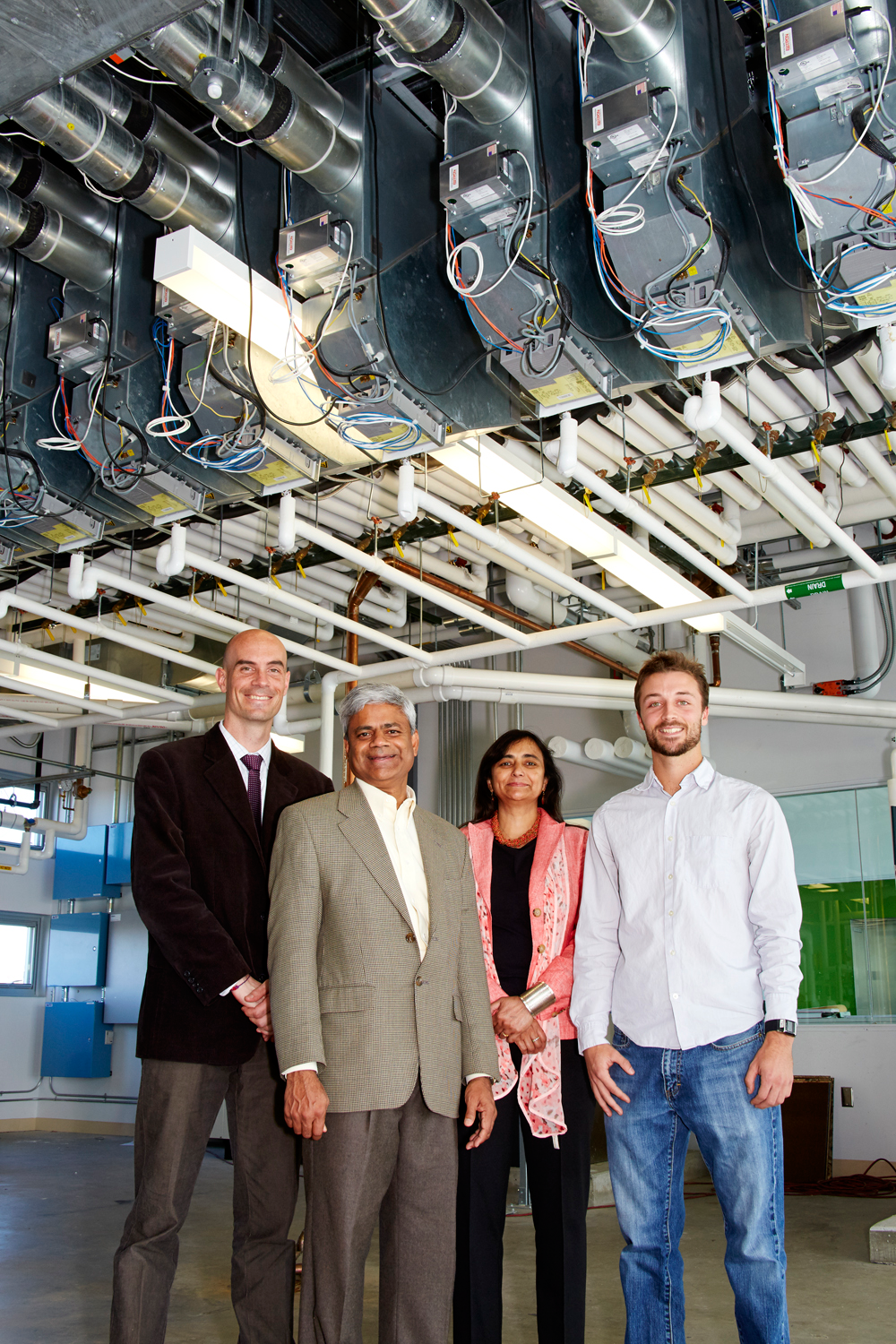

Twenty-four professionals participated in the six-day COGfx Study. Each conducted their normal work activities within a laboratory-setting that simulated conditions found in conventional and green buildings, as well as green buildings with enhanced ventilation. (Photo: United Technologies)

Architects have long focused on ways to seal buildings up and make them more energy efficient, but new research demonstrates that good ventilation can be important for our cognitive abilities. Steve Curwood speaks with Harvard School of Public Health professor Joe Allen about the new study that documents the details and with John Mandyck of United Technologies about how the findings could influence the future of building design.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Think air quality and you’re likely to consider outdoor air, full of diesel fumes and smoke and dust. But most of us spend 90 percent of our time inside. Now ground-breaking research by a team from Harvard, Syracuse University and SUNY Upstate finds that dramatically improving indoor air quality can more than double the reasoning scores of workers. Chemicals found in paints, furniture and flooring, so-called volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, are the main problems. And common office concentrations of carbon dioxide also modestly reduce cognitive functioning. The lead author of the study, published in Environmental Health Perspectives is Joe Allen of Harvard’s Center for Global Health and the Environment. Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor Allen.

ALLEN: It's a pleasure to be here. Thanks.

CURWOOD: Your study looks at the impact of indoor air quality on cognitive functioning, so tell me about the study. How did you do this?

ALLEN: We set up in the Syracuse Center of Excellence. They have a simulated office environment, and we enrolled what we called knowledge workers, people who work in office environments. We enrolled them to come to the Syracuse Center of Excellence and do their normal work routine in this office. From the floor below, we were able to manipulate the indoor environmental conditions in their workspace unbeknownst to them. At the end of each day, we administered a cognitive performance test, and the analysts are also blinded to the conditions that were testing that day, so that way it's a double-blinded study, it's a controlled environment, and we were able to manipulate one variable at a time to tease out the effect of that variable on the cognitive performance scores of people in that space.

CURWOOD: Now, how did you measure the cognitive impacts?

ALLEN: So we measured cognitive performance with a great tool called the simulated management strategy tool, and it's a neat tool because it tests real world decision-making performance. I think it's best if I give you an example. So, in one of the scenarios, the participants are asked to play a game, and they are essentially the mayor of a city, and in that role they are prompted with things that happen throughout the day and they have to respond to these prompts throughout the day, and they have a wide axis to a wide range of information, and we watch how they plan, strategize and what decisions they ultimately make in response to the information coming at them.

The research team responsible for the study (From left) Principal Investigator Joseph G. Allen, DSc, MPH, Assistant Professor of Exposure Assessment Science, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Co-investigator Suresh Santanam, ScD, PE and Associate Professor of Biomedical and Chemical Engineering, Syracuse University; Co-investigator Usha Satish, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, SUNY Upstate Medical University; and Project Manager Piers MacNaughton, MS, doctoral candidate, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (Photo: United Technologies)

It's really similar to how we all operate every day. You're sitting at your desk, you have access to unlimited information with the Internet, your phone rings, you have text messages coming in, you're answering e-mails, the boss comes in, a crisis happens, and we want to simulate this with this tool to test how people respond under this real-world scenario of dealing with information, figuring out how to use information, are they optimized, how they do in a crisis and importantly, how do you recover after a crisis, are you done for the day or do you go back to your nice strategic planning in taking actions based on the prompts are coming in.

CURWOOD: So what did you find? How did people perform these cognitive tests based on their exposure to changes in air quality?

ALLEN: Yeah, we found some quite striking results. We found a doubling of cognitive performance scores for people who spent time in the optimized green building environment compared to those same people when they were in the conventional office building, an indoor environment designed to simulate the conventional office building. And three domains, three cognitive functioning domains in particular had the strongest scores. These were crisis response, strategy, and information usage. And these three cognitive function domains are most closely tied to productivity.

CURWOOD: Those numbers are huge. That's a big disparity. How surprised were you by those findings?

ALLEN: To be quite honest, we were shocked. We think this is a big deal, that the findings are strong, the magnitude of the effect is quite large and the really nice thing about the studies is that we weren't testing anything exotic. We didn't introduce chemicals into the environment that you don't typically encounter. We didn't introduce ventilation rates that are impossible to obtain. The idea was to simulate office environments that can easily be obtained. So these are chemicals that we are commonly exposed to, these are outdoor ventilation rates we can obtain in most buildings. So this is what's shocking is that you see this big effect - the magnitude is big, and the effort it takes to reach that wasn't that much.

CURWOOD: Joe, how does all this indoor air pollution affect us physiologically? How do you get from the chemical to cognitive impairment?

ALLEN: Well, this is a great question and it's currently unknown, so there's no answer right now, but we hope and we know - there are people working on this and we're starting to work on it too - is the next question is why is this happening, or how is it happening...so physiologically, mechanistically what's happening that's causing this decrement or in some cases improvement in cognitive performance functioning. So we think that the next six to 12 months we'll start seeing a lot of researchers attacking that question.

CURWOOD: So let's be specific about these chemicals. What's the impact of the Volatile Organic Compounds, the VOCs?

The study was designed to determine the independent and combined effect of volatile organic compounds, ventilation and CO2 on workers’ cognitive function. These factors were controlled by a machine room located directly below the workspace. (Photo: United Technologies)

ALLEN: So VOCs...I mean, we're exposed to VOCs every day in just about every environment we're in, and we know they cause things like eye irritation or upper respiratory irritation, some of them are carcinogens, so we know these compounds can be irritants, and now we're learning that they can also impact cognitive function.

CURWOOD: Now, what about carbon dioxide?

ALLEN: Yeah this is very interesting. So, the second part of our study we looked at the impact of carbon dioxide on cognitive function, independent of ventilation - outdoor carbon dioxide concentrations are typically around 400 parts per million right now. Indoors, we routinely see carbon dioxide between 800 and 1,200 parts per million, but it's not uncommon to see carbon dioxide as high as 1,500 parts per million or even up to 3,000 parts per million. So we found in our study is that when people were in an environment with low-carbon dioxide concentrations and they were moved to a level of about 950 parts per million, a level we find in most indoor spaces, we see a 15 percent decrease in cognitive performance scores for the people in that space, and when they move to an environment with 1,400 parts per million, we saw 50 percent lower cognitive performance scores when they were in that environment.

CURWOOD: So, a huge impact.

ALLEN: Yeah, very big. I mean this is new for our field. Carbon dioxide, we measure it all the time when we're doing studies of buildings and health because it's a good indicator of how well the space is ventilated. But now we’re starting to see that maybe carbon dioxide isn't just this useful tool as a proxy for ventilation and other things that are building up in our environment. It might actually be a direct pollutant, a primary pollutant.

CURWOOD: So you say that there's this is decrease in cognitive functioning when you have poor air quality or even conventional office air quality compared to greener air quality. How do you translate that into dollars and cents, let's say, for a company looking at its workers?

ALLEN: Yeah, I'll tell you about our next paper that we publish that should be out in the next month or two because we thought this was a really important question to ask is how can we take the data we have now on cognitive performance and turn it into dollars because we know that research informs practice, and what a lot of these practitioners want to hear is how is it going to impact my bottom line. So we looked at the energy penalty, or the energy cost for increasing outer air ventilation to the levels we did in the study where we found a benefit of cognitive performance and we find that it's on the order of $30 per person per year to double your outdoor air ventilation rate. Then we used the same information from our study and look at the cognitive performance improvements normalized to what we find in the general population and we estimate that the benefits to productivity are on the order of $6,000 per person per year.

CURWOOD: So what do you hope comes out of this study?

ALLEN: We designed the study specifically to look at what building factors could be improved that would lead to benefits to cognitive performance of people in that space, and there's a positive story here is that there are things we can do right now in most spaces that will reduce the chemical concentration that we're exposed to and can increase the amount of air coming in, and we think this will lead to better cognitive performance based on the results of the study.

CURWOOD: You know, when you do a home energy audit, they come and they do this pressure test to see how much leakage you have, and the less leakage you have the more efficient the home is. To what extent is this a zero sum game if you improve indoor air quality, you have less energy efficiency?

ALLEN: Yeah, Steve, I think it's a false choice we've been given over the past 30 years where there has been a trade-off traditionally between energy efficiency and human health, and that can't be the way we move forward. And we know that you can make decisions now in how buildings are designed and how your ventilation system is performing and the choices in the products you make can be used to optimize indoor environmental quality while optimizing energy performance and cost.

CURWOOD: Joe Allen is an Assistant Professor of Exposure Assessment Science at the Harvard T.H. Chan school of Public Health. Thank you so much.

ALLEN: My pleasure. Thank you.

CURWOOD: For an industrial perspective on the implications of this Harvard-led research we turn now to John Mandyck, chief sustainability officer for the United Technologies Corporation. UTC is the world’s largest provider of building technologies, and the key underwriter of the study, but was not involved in the data collection, analysis, interpretation, or drafting of the peer-reviewed paper. John Mandyck says these findings may revolutionize the way we think about buildings.

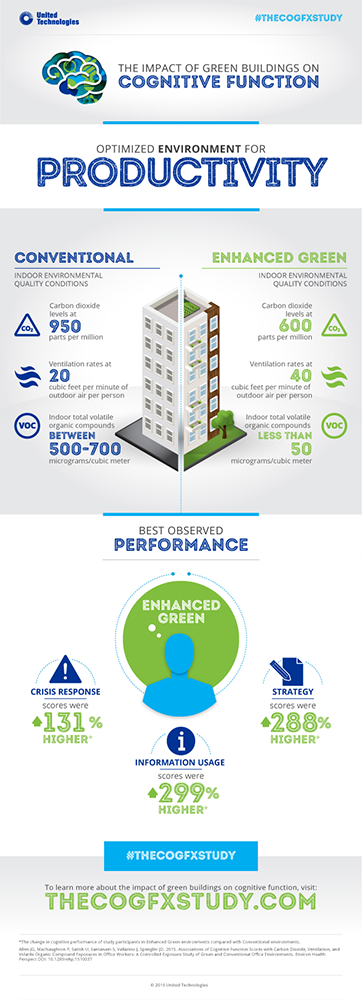

Infographic of the results (Photo: United Technologies)

MANDYCK: The study that Harvard and its research partners has done has the potential to change everything for how we think about buildings. We have to have the laboratory basis of the analysis to set the baseline. Now with that baseline which is a very, very strong baseline and the correlation of green buildings and cognitive impact, we're now going to test that baseline in 10 buildings around the country.

CURWOOD: How might this“change everything”to use your words?

MANDYCK: I think this can change everything because better thinking and better buildings means buildings can become competitive assets for companies. It's a way that companies can differentiate themselves to get a competitive advantage. Think about this: the research that Harvard and its study partners have found is that with optimized indoor environmental quality, test scores over nine cognitive domains doubled. That really means better thinking in better buildings, and I think what's most important here is that productivity often comes with a learning curve. In this case, all people have to do is breathe because the intelligence is in the air with the optimal and readily achievable conditions that Harvard and its study partners found in this research.

CURWOOD: Now, for years, people sold building energy efficiency on the basis of payback because you could see the math, you put in so much insulation you save so much in terms of using fossil fuel, and you could see the money going right to the bottom line. How does this study, how does this research, help you sell better quality with a measurable payback?

MANDYCK: Well the basis for the research is to accelerate the green building movement overall. As you pointed out, energy has been a very important value mechanism in ways that we approach green buildings, that if we build green buildings they save energy, they save water and you receive a natural pay back from that. We've done very well with that type of analysis. Last year, the green building market for the commercial sector in the United States reached about 47 percent. So we've come very, very far, but the interesting thing here if you look at the true cost of operating a building, just one percent is energy. Ninety percent of the true operating cost of a building are the salaries and the benefits of the people inside the building. Green buildings can improve thinking, can improve productivity, can improve health. Buildings can become human resource tools now. Buildings can become ways that we can find competitive advantages simply by optimizing the indoor environmental quality.

CURWOOD: John Mandyck is the Chief Sustainability Officer of United Technologies. And by the way, UTC is also a supporter of Living on Earth. There are more details at our website, LOE.org.

Links

Study: The Impact of Green Buildings on Cognitive Function

More about the study and its implications from United Technologies

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth