Greening Death

Air Date: Week of October 30, 2015

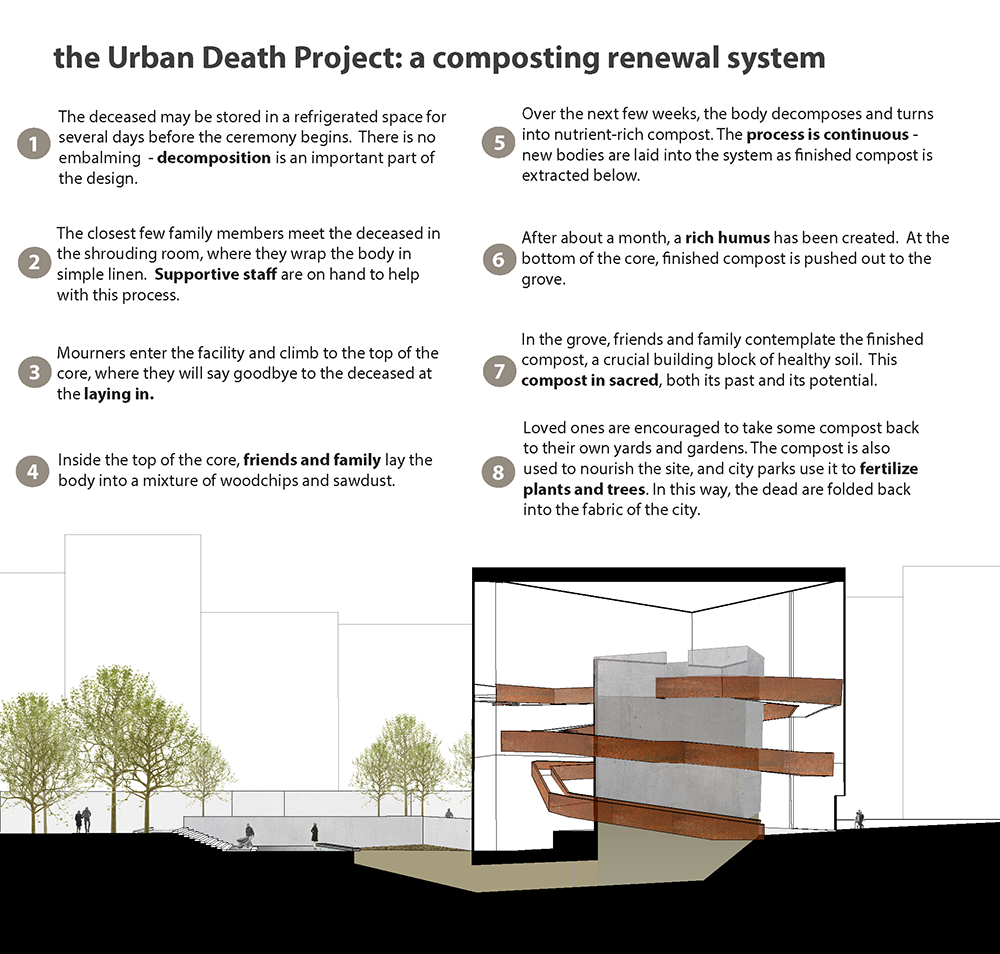

The Urban Death Project proposes that, after a ceremony, families lay the deceased in a field of woodchips. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

Each year, five million people die in the US. About half of them choose conventional burial and half choose cremation for their body, both methods that consume resources and pollute the air and earth. Now there’s a greener alternative on the horizon, the Urban Death Project. Katrina Spade, founder and executive director, explains Urban Death Project and tells host Steve Curwood how this environmentally-consciousness choice can bring meaning to death.

Transcript

CURWOOD: For thousands of years our ancestors have been laying the dead to rest and not much has changed. The departed were usually laid in the earth or on a funeral pyre. Those are still the most common methods today. But a new paradigm is on offer.

SPADE: The Urban Death Project is an alternative to cremation and burial that uses the process of composting to turn us into soil.

CURWOOD: Katrina Spade is founder and director of the Urban Death Project. The concept came to her when she was doing a master’s degree in architecture and started to think about mortality – and what happens next.

SPADE: I started looking into the options that we have available in this culture, and for the most part, it's conventional burial with embalming in casket and grave liner or cremation. But in researching it I found that it does, of course, burn fossil fuels and all the cremations in the US are the equivalent of 70,000 cars driving the road for a year. You know, it is a significant source of pollution, but I think we're importantly it doesn't hold particular meaning or relevance for me and I think for lots of people in our culture we choose it because it's kind of the best option there is, and so being in architecture school I thought maybe I could set out to design another option that would be meaningful for more people.

Compost from the Urban Death Project would be used for gardens on the premises, in local parks, and families could take some and spread it in a place special to them or the deceased. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

CURWOOD: So what does your design look like and how does it incorporate elements of meaningfulness and environment consciousness?

SPADE: Well, the Urban Death Project is a proposed type of programming for our cities and to me the reason that composting oneself is meaningful is due to the fact that rather than destroying the nutrients in our body after we've died that we've been kind of collecting over the years that we've been living on this earth, we're able to be productive one final time and use those nutrients to grow new life. So the meaning for me is very much in the process itself.

CURWOOD: So if someone were to decide this is how they want their remains handled, what's the process you would use here?

SPADE: Well, let me back up a little bit because when I was in graduate school thinking about my impending mortality, I stumbled upon research done into livestock mortality composting. So there's been a bunch of agricultural institutions including Cornell and Washington State University, and what they find is that if you lie a high carbon material down, about two feet of wood chips for example, or wood chips and sawdust sometimes, put the animal on top and lay another two feet of the same high carbon material over the top the animal in about 3 to 6 months, the animal has completely composted, including the bones. So you're creating the environment, so that the microbes and beneficial bacteria can do their job. So that environment includes the right ratio of carbon and nitrogen. It also includes oxygen and moisture.

Each year, millions of resources go into caring for our dead in the US. The Urban Death Project plans to cut that number significantly. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

CURWOOD: So now, it's one thing to do this with a cow. People would be a different situation because you can't pile this bit of carboniferous material on top of the departed Flossy in the back 40 there. People tend to be more formal. What are you suggesting people do?

SPADE: So, as an architecture student my job was to take this research into livestock composting and redesign it for the human experience. So, what I've designed are buildings inside of which there is a three-story core where the composting process takes place, and around the core is a series of ramps. The living carry the dead up to the top of the core. There is an individual ceremony and a memorial service that occurs and then bodies are stacked vertically in this core and they're separated by about 10 feet of wood chips. In the second stage of the process after the bodies have turned to a coarse compost will have a screening and a sorting, for example, golden teeth or titanium hips, and with gravity and the settling and decomposition of the material, they actually travel downwards in the core and then the coarse compost will be refined and finished and cured. So it's very much still a natural process and I've tried to keep it as simple as possible. One of the most amazing things to me is the fact that families by doing this are actually beginning the transformation of their deceased from human to soil and to me that's quite beautiful.

Using this composting renewal system, Spade’s group estimates that it will take 4-6 weeks for a body to fully compost. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

CURWOOD: Katrina, in your process, when the composting is done, how are relatives going know which of the soil that’s been created is really Aunt Martha?

SPADE: At this point, there is no individual output. So that's a decision that I made early on in part because we're all part of a greater ecosystem, and so I just don't feel that it's necessary for us to have our individual person’s soil.

In Spade’s design, the living will carry the dead up 3 stories using ramps that wrap around the composting core. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

CURWOOD: How long does your process take?

SPADE: Well one of the things that we're figuring hearing out with our partners at Western Carolina University is exactly how long it will take for a human to decompose, and so were estimating right now about 4 to 6 weeks, but we still figuring out the details.

CURWOOD: Since we just can't compost a body anywhere, what legal or design issues do you think still need to be worked out?

SPADE: How you can treat a body after death is regulated on the state level. So, most states allow conventional burial, cremation, sometimes natural burial and often donation to science. What it's about is adding the method of composting to that list on a state-by-state level, but down the road if you really want to know what I envision is that death care would be part of our healthcare continuum, it would be free and available to all people, and that it would be municipally run. These places would be public spaces in our cities much like our library system or library branch.

CURWOOD: How do you think our views about ecologically conscious burial might influence the acceptance of human composting?

Urban Death Project founder and executive director Katrina Spade (in green) consults with scientists and planners to design each building and site. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

SPADE: I think that the time is very right for this project. I've gotten such amazing support for it. I think that from an environmental perspective people are realizing that they don't want their last gesture to be polluting or wasteful. I guess I want to say also that it's really more about finding something that's meaningful, so if cremation is meaningful to you, by all means, it's a great choice because we pollute all the time during our daily lives. It would be really hypocritical of me to say you shouldn't do this one last little bit of pollution just because you died. I think the same thing is true for conventional burial, but the truth is that for so, so many neither of those options really resonates.

CURWOOD: Katrina Spade is the Founder and Executive Director of the Urban Death Project in Seattle. Thank you so much, Katrina.

SPADE: Thank you so much for having me.

Links

More about the process, possible stigmas and the possible involvement of religion or spirituality

Kickstarter: the Urban Death Project: Laying Our Loved Ones to Rest

Promessa Organic AB: composting corpuses but in a different way

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth