Hope and Concern Sparked By Paris Climate Deal

Air Date: Week of December 18, 2015

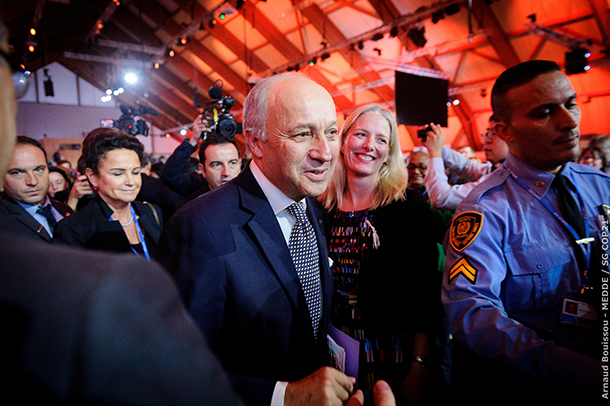

COP21 President Laurent Fabius, following the adoption of the Paris Agreement. (Photo: COP PARIS, Flickr Public Domain)

In Paris, nearly 200 countries ratified an agreement outlining climate action commitments aimed at restricting global temperature rise to 2 degrees or less. Host Steve Curwood analyzes final remarks from Secretary of State John Kerry on the power of American business, former UNFCCC critic Claudia Salerno of Venezuela’s preamble, and a “technical error” which could have derailed everything. Also, Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer polls delegates from developed and developing nations on the outcome, including Edna Molewa of South Africa, Miguel Arias Canete of the European Union, Paul Oquist Kelley of Nicaragua, Peter Hans Emberson of Fiji.

Transcript

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, back with our crew from the climate summit in Paris. Coming up in today’s program, we’ll take a look at where the Paris Agreement might or might not head us in the future. But first, a look back at this historic compact among nearly 200 countries aimed at keeping the world from climate disaster, an agreement that prompted praise and jubilation from its architects.

KERRY: This is a tremendous victory for all of our citizens, not for any one country or any one bloc, but for everyone here who has worked so hard to bring us across the finish line. It's a victory for all the planet and future generations.

CURWOOD: Secretary of State John Kerry had put US credibility on the line to make it happen – and he thinks that business will flourish as a result.

KERRY: We are sending literally a critical message to the global marketplace. Many of us here know that it won't be governments that actually make the decision, or find the products the new technology, the saving grace of this challenge. It will be the genius of the American spirit it will be business unleashed because of 186 nations saying to global business in one loud voice we need to move in this direction. And that will move investment, that will create new greater research and development, and the next great product will come that will change our lives.

Secretary of State John Kerry highlighted the relevance of the Paris Agreement to strengthening American business. (Photo: COP PARIS, Flickr Public Domain)

CURWOOD: And it does seem Paris will be good for the economy, though it remains to be seen just how good it will be for the environment and human progress, as it put no overall cap on global warming emissions, and raised as many questions about equity as it answered.

But this unique moment of near global unity prompted national delegations to speak after the COP21 pact was formally accepted, including Claudia Salerno of Venezuela, an outspoken critic of the UN process during the failed COP15 in Copenhagen.

She played a critical role in writing the non-binding preamble of the Paris Agreement, which declares its moral imperatives.

SALERNO SPEAKING IN SPANISH: (TRANSLATION): ...which I believe is really revolutionary because it welcomes all these social dimensions of climate change, and this will be a direction for the implementation of the agreement. Retaining concepts such as gender equality, the empowerment of women, equity, intergenerational equity… [APPLAUSE] …the rights to health, climate justice, the right to development, Mother Earth, and in particular, human rights. [APPLAUSE]

Former UNFCCC critic Claudia Salerno of Venezuela wrote the preamble to the Paris Agreement. (Photo: Arend Kuester, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: And the climate envoy also earned huge applause when she announced that Venezuela would support the agreement. Achieving this breakthrough in Paris was a high-wire act right to the end, and was nearly sunk by a small word change in a clause about developed countries making economy-wide emissions reductions. A conditional “should” that had been negotiated earlier suddenly became a declarative “shall” – in the last draft. The US delegation said it couldn’t sign on, as the deal would impose a mandate beyond those in original UNFCCC treaty, which was ratified by the Senate back in 1993.

But there is a reason “finesse” is a word rooted in French, and COP21 President and French foreign minister Laurent Fabius found a diplomatic solution: a technical error had been made. He declared the text agreed and gaveled it through. As delegates left the plenary hall they were met by a scrum of reporters including Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer. Hey, Helen what a night!

PALMER: Yeah, all those diplomats, dozens of TV cameras and microphones pointed at them like teeth as all the folks trickled out! But most of the delegates were really beaming though - including the head of the South African team, she’s also the leader of the G77 group of developing nations, it’s the Environment Minister Edna Molewa. She says the 2011 Durban conference laid the foundations for this breakthrough.

MOLEWA: What a long way – a 4 year journey of hard work, dedication, commitment, determination to make it. And here we are, finally we’ve got an agreement, legally binding agreement, that’s actually universal, everybody covered, everybody's happy. Now we're got to get down to work, and we are saying in our statement that even though we have been focused much more on getting this agreement which is post-2020 we have to focus on the pre-2020 action because action doesn't have to start only after 2020, we have got to act now.

CURWOOD: So were they all so glowing and upbeat?

PALMER: Well mostly they were very positive – I mean take the climate change commissioner for the European Union, Miguel Arias Canete.

CANETE: With this Agreement, we're going to stop global warming below the two degrees, or 1.5 – without it, the temperature will be increasing year by year. Now we are in a pathway to 3 degrees. And if we raise the level of ambition over time, we will be able to stop global warming below two degrees, and that's what the world needs, but mainly the poor, because climatic phenomena are more dramatic

for the poor people.

CURWOOD: But what about the delegates from those poorer nations. How did they react?

PALMER: Well, some interesting and ironic comments came from the Nicaraguan climate envoy, Paul Oquist Kelley – who spoke very harshly against the deal after it was agreed. He had some ideas why Europeans and other developed countries might be pleased with the deal.

KELLEY: Oh, I was thinking about the people in Europe, having longer time for vacations, September and October will be nice and warm. You'll get more areas you can grow in in Russia, and in Canada. You'll be able to cross the Arctic on boats, without ice; you'll be able to drill fro more oil in the Arctic, a lot of people are really enthused about that. So while Europe is applauding that, we are boiling, we are being fried, it's not a nice comparison, but I think that we need more empathy for the situation in the Sahel, in Central America, the small island states, and the consequences of climate change further.

CURWOOD: So what about the delegates from the small island countries at risk of seeing their lands literally disappear under rising seas? After all, they helped drive the adoption of the goal to hold global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees. Were they equally unhappy?

PALMER: Well, they did still have some problems, but the ones I spoke to weren’t unhappy. I caught up with the climate change envoy of Fiji. His name’s Peter Hans Emberson.

Edna Molewa of South Africa with Laurent Fabius. (Photo: COP PARIS, Flickr Public Domain)

EMBERSON: Yes, I’m very happy with what has transpired here at COP21. The language and some of the particular elements that references the vulnerabilities of Pacific small island states, it has been an enormous victory for small island developing states, especially on the anchoring of loss and damage. I think that is a big achievement for us because there are limits to adaptation, there is only so much communities and nations can do about rising sea levels and for low lying coastal areas, they are particularly vulnerable to coastal inundation, storm surges and eventual sea level rise that will take away large tracts of lands that are low-lying.

PALMER: And that's the case in Fiji, is it?

EMBERSON: Yes, we relocated two communities. It's been an ongoing process of now three years. We've identified 45 communities that will be needing to move after an assessment of 800 communities vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, and we are finding that it's an expensive exercise. It's a traumatic exercise. So, yes, loss and damage here at the Paris COP21 is an affirmation of the work we are already doing underground to prepare people and to identify tracts of land in higher elevation for people to move to.

PALMER: And you have the land?

EMBERSON: We do you have the land. Some communities have the land to move to, but the actual moving of essential infrastructure - hospitals, churches, schools - the actual moving is quite costly so we are having to do it in phases, and some of these plans are 10 to 15 years because of the high expense that's involved.

PALMER: So, yes, loss and damage is in the Agreement, but the question of the money for loss and damage is very unclear.

EMBERSON: The importance of finance will always be something of a work in progress, and we appreciate the establishment of the green climate fund and the bankable projects that have been approved last month in November in Livingston, Zambia. Eight projects have been approved, so this indicates there is some movement, however slow, it is an affirmation that climate financing is going to be made available. Financing is an important means for implementation and I think countries recognize that but we still have to plan and once these plans are in place in the agreement then we could then move to financing, to urge nations with the ability to do so to do the right thing by providing monies for adaptation as well as mitigation to ensure that appropriate technologies to drastically reduce the causes of climate change.

Miguel Arias Canete of the European Union. (Photo: European Parliament, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PALMER: What is not there that you really wanted to be there and you're disappointed about it?

EMBERSON: Lack of clear articulation on legally binding. That's important to us because not only are we mitigating at the national level far, far beyond our capacity, but we are seeing we have to reduce our dependence on fossil fuel because that is the future. We need to transition into low-carbon dependence. And Fiji has done that, and a lot of small island developing states have done that. All countries should also be doing the same ambitious deep emission cuts, and the lack of a legally binding language, it makes it voluntary, and when it is voluntary, there is no urgency to do something now to put things into policy and to ensure that we are working towards safeguarding the planet's future. If it is voluntary, countries will take their merry time and to the detriment of small island developing states and other vulnerable states.

PALMER: People have been pointing to the power and maybe the moral force of the small developing nations in actually making this agreement happen. What made the small island states and the small developing states and the least developed countries give this big push?

EMBERSON: The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and small island developing states, we've long recognized that we don't have much by way of resources. We are not Annex I countries that can deliver financing.

PALMER: Annex I are the rich countries?

EMBERSON: The rich countries. That's right. But what we have is the moral imperative to come and make a strong voice here is part of our very existence. We come to the United Nations process to tell our stories, that your lifestyle is affecting mine, and if we have to co-exist as one people on this planet, then we need to look after the safety of our brothers and sisters in another distant parts of the world.

CURWOOD: So that was Fiji’s director for Climate Change, Peter Hans Emberson, speaking with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer. And, Helen, is there any kind of final comment from the aftermath of the agreement?

PALMER: Well, one of the most charismatic of the NGO leaders is Kumi Naidoo of Greenpeace International. Here’s what he had to say to sum up the message of COP21.

NAIDOO: This is neither the moment for triumphalism nor despair. We cannot afford to be triumphalistic with this deal, when in fact, hundreds of thousands of people have died already from climate impacts because too many powerful governments dragged their feet for 20 years; nor can we be triumphalistic when we know that hundreds of thousands of people are living on the precipice of climate impacts right now. On the other hand, this is not a moment for despair, because the climate movement can take real comfort from the fact that we have won the debate, that the fossil fuel companies now find themselves on the wrong side of history, and that we now need to intensify our efforts to ensure that the emissions targets that are on the table, which takes us to a 3 and a half degrees world, are actually increased in ambition.

CURWOOD: Kumi Naidoo of Greenpeace International. Just ahead - analyzing what comes next, with the Paris Agreement done. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

Links

How a 'typo' nearly derailed the Paris climate deal

Paris climate change agreement: the world's greatest diplomatic success

Kumi Naidoo reacts to conclusion of COP21

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth