Figs: The Vital Forest Species

Air Date: Week of January 20, 2017

Fig wasps and tiny figs (Photo: Jnzl’s Photos, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Fig trees are one of the world’s most diverse groups of plants, and have fed people and thousands of other species for millennia. Mike Shanahan, author of Gods, Wasps, and Stranglers: The Secret History and Redemptive Future of Fig Trees, tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer about the unique ecology, mythology and cultural value of fig trees, and how they can help us care for and protect nature.

Transcript

PALMER: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Helen Palmer in for Steve Curwood. Every man sitting under his own fig tree is a Biblical vision of peace and prosperity, and it’s not just a fantasy. Figs have fed people for millenia, and they’ve developed complex partnerships with animals, insects, and plants. They’re also prominent in culture and mythology. And they might even have the potential to help shape our future, says author Mike Shanahan. In his new book, “Gods, Wasps and Stranglers: The Secret History and Redemptive Future of Fig Trees", Shanahan shares stories from the days of his field work studying rainforest fig trees, and explains their unique place on the tree of life.

SHANAHAN: Well, they're really fascinating plants. They've been around on the planet for about 80 million years, so they lived when the giant dinosaurs were still roaming around, and they have a really special relationship with some tiny wasps that pollinate their flowers. And each of the fig species, and there is something like 750 different species of figs, each of them has its own wasps that pollinate the flowers, and the flower are found inside the figs. And the wasps can only breed in those flowers, so they have a very tight relationship. Each one depends utterly on the other.

PALMER: So, does this means that when we eat figs, we're eating wasps?

SHANAHAN: In some cases maybe yes, but often not because the wasps often have departed from the figs before we get to eat them, and some of the edible varieties that we eat are actually species that farmers have developed over many thousands of years to produce figs without the need for their pollinators.

PALMER: Gosh. So, you say they've been around for millions of years. Are they kind of anchor species in different ecosystems?

SHANAHAN: Yes, they are. They're what biologists call keystone species. If you imagine a bridge, the keystone is the stone that locks all of the others in place. But if it goes, the whole bridge comes tumbling down. And because figs have this relationship with their wasps, they produce figs all year round, and this means that they feed a huge number of animals in rain forests around the world. Altogether, more than 1,200 species of birds and mammals eat figs around the world and so they are a massively important food resource, and those animals are the dispersers of many other tree species. So, if you take figs out of an ecosystem you take a lot more besides.

Vervet monkeys are among the many creatures that rely on fig trees for sustenance. The close relationship between most fig trees and their pollinator fig wasps enables the trees to produce a year-round supply of figs for forest animals (Photo: Bernard DUPONT, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

PALMER: What got you interested in figs in the first place?

SHANAHAN: Well, I learned about them a little bit when I was an undergraduate student of biology and when I was doing a masters project I was meant to be going to study birds in Indonesia, but the project fell apart and my supervisor felt a little bit guilty, and so he contacted some of his colleagues who were fig biologists like him and one guy in Borneo Rhett Harrison replied and said, yes, he could host a student for a couple of months. So, I went out and lived in the rain forest in Borneo and my project turned into a doctorate. So, I spent three years studying the figs there and elsewhere.

PALMER: That sounds pretty exotic, Borneo.

SHANAHAN: Yes, it was great. It was fantastic. I was living in a national park, which is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet really. It’s got thousands of species living there and has probably 75 or 80 different species of figs just in one place, so it's a real center of diversity. It has figs that are tiny shrubs, and some that are creepers, it has strangler trees, it has trees that produce the figs from the main trunk of the tree. It's even got some figs that produce their figs underground, on runneers underground. So, there's massive variety all in one place and it made it really good place to the study interactions between animals and plants there. And it was a fantastic field site. We had an aerial canopy that allowed us to walk through the canopy level of the rain forest on walkways and towers and observe life really where it's all happening up there in the top of the forest.

Shanahan's book is Gods, Wasps and Stranglers: The Secret History and Redemptive Future of Fig Trees (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

PALMER: So, those green or purple things that we see and periodically find in the shops and mostly find in cookies and biscuits and the like, that's not what most figs are like.

SHANAHAN: That's right. There's a whole variety. They come in all shapes and sizes, different colors. They can be as smaller that a pea or they can be bigger than a tennis ball. Some of them are hairy, some of them are smooth, some of them are purple, black, orange, gold. All these different colors. And all of this variety is reflected in a sense in the variety of animals that come to eat those figs. So, you'll find that bats like to eat figs that are green and smelly and birds like to eat figs that are bright red.

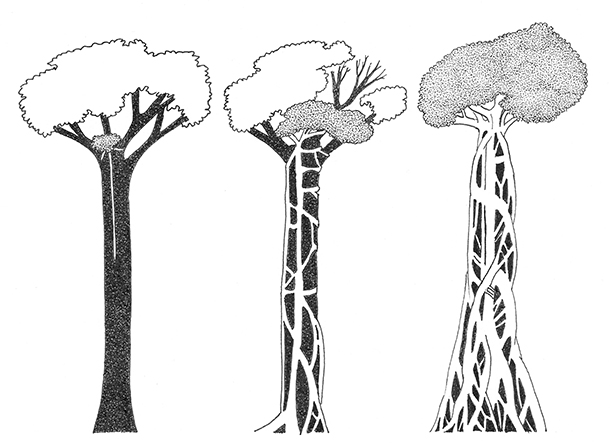

PALMER: You talk -- you give a great description actually about strangler figs. Can you describe what they are?

SHANAHAN: Well, most plants start out in life on the ground and grow upwards, but strangler figures do the opposite. They start out in life as a seed that is dropped from a bird or a bat or a monkey or some other animal, and which lands high up on a tree in a rainforest, and that seed then germinates and sends down some roots which descend all the way down the host tree wrapping around it, merging, splitting, merging again until there's a basketwork that's spread all around the host tree, and this is what a strangler fig is. You can have situations where the host tree dies and what you have left is a hollow column and you can go and step inside it and look up and see this architecture that has been created from the top down. And these trees are the ones that are really important for wildlife in the forest because they feed a huge variety of birds, bats and other creatures, and they produce up to a million figs more than once a year, so they're like pop-up restaurants in the rainforest.

A strangler fig germinates high in the branches of its host tree, sends down roots, and gradually robs the host of light and nutrients. (Illustration by Mike Shanahan)

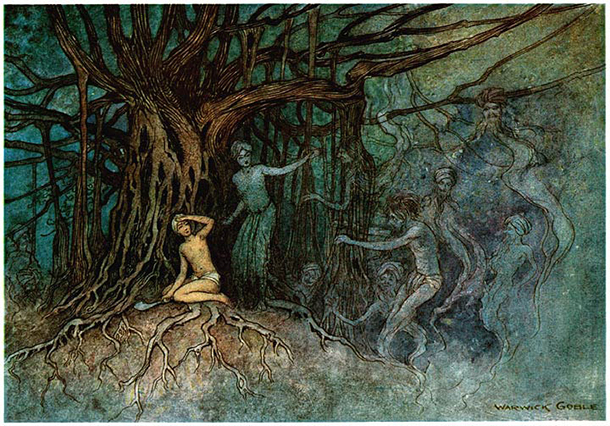

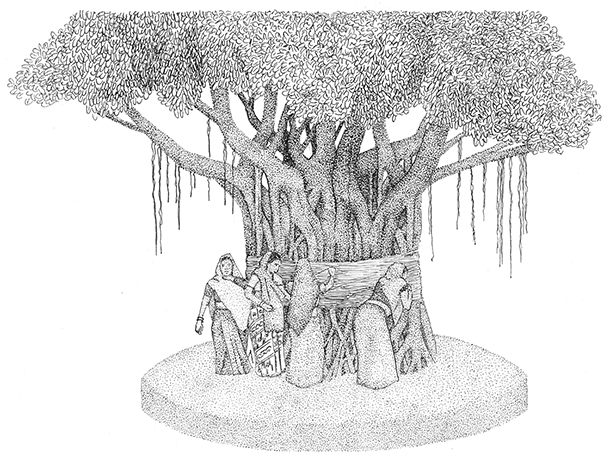

PALMER: You talk about them as keystone species, but they've also become hugely important mythological species in many, many cultures. Why is that?

SHANAHAN: Well, yes. They're found in every major religion, they're found in traditional cultures all around Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Pacific, Australia and more, and part of the reason is their biology. So, some of these trees are really awesome things to look at, the strangler figs and the banyans, and no doubt they captured the imaginations of people a long, long time ago. Also, they're very important ecologically. So, it would make fine sense for any society that protected these trees because they would get the benefits of what the trees do in the environment by sustaining the wildlife and also by providing other goods and services that people can benefit from. Many are also sources of traditional medicines and of shelter, of shade and all of these things together have combined to allow these trees to be embedded in human cultures to the extent that's all around the world there are taboos against chopping these trees down. In Madagascar and India and Mexico, you'll often find that a forest has been cleared, but what's been left standing is a fig tree. Now, it's very different in the very modern time. Now, it's much more likely that you'll see fig trees being cleared, whether it's to widen roads or to increase agriculture. So, we are at a moment in time where perhaps those old lessons from the past should be remembered again.

When a strangler fig's host dies a hollow core remains (Illustration by Mike Shanahan)

PALMER: So, you think they still have a really vital importance for us?

SHANAHAN: Well, they do, because forests are falling all over the world, and especially in the tropics. And the more forests fall, the less we can use forest to protect ourselves from climate change. And in fact, there are people who are using fig trees in different countries now in order to boost rainforest regeneration. The idea is if you plant fig trees, you attract lots of other animals that disperse the seeds of different tree species and the rain forest recovers quickly. And this has happened in Thailand, in South Africa, in Costa Rica and in Rwanda. All of these projects are currently ongoing right now.

PALMER: That sounds really interesting. You talk in your book about how fig trees are able to colonize places, which seem incredibly inhospitable like lava fields after a volcano. Tell me a bit about that.

SHANAHAN: That's right. I've been on a volcano that was just bare lava, and there was a tall fig tree growing there. It's interesting that all of the other plants in that area were little weedy grasses, but there were several fig species growing in this bare lava. And if you go to any Asian city, you will find fig trees growing out of walls, you’ll find them growing off the top of buildings. They can germinate in pretty much bare ground. Their roots are very strong, and they can rip apart rock even. So, these trees are very good at colonizing land that really looks beyond repair, such as a mining site. And once the fig trees get in and start breaking up that substrate, they allow water and oxygen to get in, soil starts to form, and other plants can then follow onwards.

In a Bengal folk tale, ghosts assail a man who tried to cut down a banyan tree (Illustration by William Goble)

PALMER: Wow. You also talk about places where the fig wasps died out and so they aren't actually managing to fertilize the figs anymore.

SHANAHAN: Well, there have been times when fig wasp populations have just disappeared almost overnight in different parts of the world. So, where I was in Borneo, there was a really really intense drought in the late 1990’s and lots of the fig wasp species just went locally extinct. They couldn't handle the heat, and also the fig plants stopped producing the figs. So, the wasps had nowhere to go, and what happened was that the wasps eventually returned after several months, but for a long time there was no pollination happening, no seed production happening, and animals in the forest were probably going quite hungry. They tend to bounce back though because these tiny little insects can travel huge distances in just a couple hundred days in which they live. And in time, they can return to these areas where they've been taken out from.

In an ancient Hindu tradition, married women tie threads around a banyan tree and pray for their husbandsí wellbeing (Illustration by Mike Shanahan)

PALMER: Yes, actually you describe what a short period of time the fig wasp has to do the important job it has to do. Explain to me how that works.

SHANAHAN: Well, when a fig wasp is born, the female emerges from within the flower where she's developed inside a fig, and she mates with the male and then pretty much that's it. She's off. She leaves the fig having picked up some pollen and now she own has about 24, 48 hours to reach another fig of the right species in the right stage of development that will let her enter so she can go in, lay her eggs, and also deliver the pollen that she's brought with her from the fig of her birth. And in that two days, that's not a very long time but she tends to fly up into the high levels above the forest and the wind will blow her a long, long way in a short time. We've got some evidence that figs can transmit pollen for 160 kilometers, which is about 10 times more than any other insect have been recorded doing that.

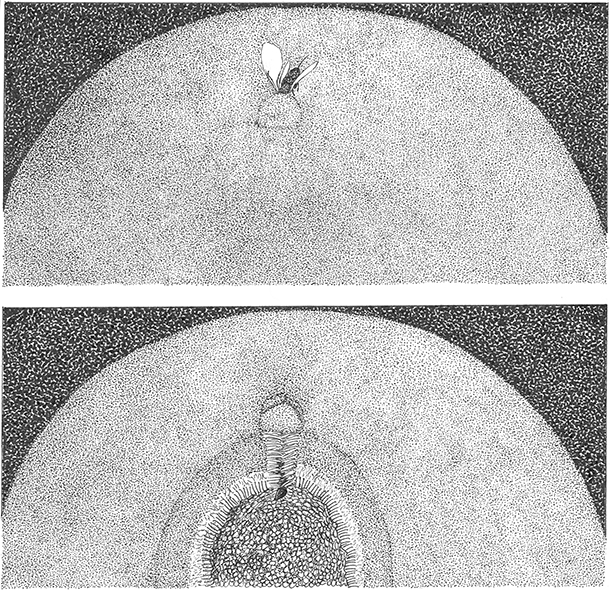

A female fig wasp must force her body through a tiny hole in the skin of a fig to reproduce, and loses her antennae and wings in the process (Illustration by Mike Shanahan)

PALMER: And it's very dramatic when they actually get to the fig.

SHANAHAN: That's right. Each fig has a tiny little hole in it, which is the entry hole, and the pollinator wasp must force her away in this hole. So, she sticks her head in, and her head has been adapted over millions of years of evolution to be the right shape for forcing her way in. And as she squeezes her way in, the antennae will be wrenched from her head and the wings will be pulled from her back and she eventually finds herself in the hollow heart of the fig where she's got her egg laying and pollination to do, and she doesn't need those things anymore ... her wings ... because she's going to die inside that fig.

PALMER: So, every single fig sees the sacrifice of many fig wasps.

SHANAHAN: That's right. Well, the females that arrive and lay their eggs, they aren't sacrificing much because they're passing on their genes to their offspring. But there's also a whole other battleground inside the fig because there are plenty of other parasitic fig wasps that come along and lay their eggs in the offspring of our pollinator fig wasps, and there's a whole drama that goes on between these different species.

The female fig wasp deposits her eggs into the tiny flowers inside the fig (Illustration by Mike Shanahan)

PALMER: So, at a very tiny level this is nature red in tooth and claw?

SHANAHAN: Exactly.

PALMER: As you describe it, these become the most fascinating species. But what was it that got you about them really.

SHANAHAN: Well, I always came from it from the wildlife angle. I was amazed that so many different things eat the figs. We're talking about elephants and rhinoceroses eating figs. There are hundreds and hundreds of bird species and monkeys and fruit bats, but also weirder things. There are fish and there are tortoises that have been recorded eating figs. Even lizards dispersing the seeds of figs. So, it really struck me that this whole Noah's Ark of animals was feeding off one group of plants. It was pretty amazing, but it was later on when I started hear about all of the cultural stories about figs that I really got more excited about this idea and that there might be a book in this. And since then I just can't stop myself finding more and more interesting things about these plants. They have so many superlatives about them that I felt it was definitely the time to write a book about these things.

PALMER: Superlatives such as?

SHANAHAN: Well, some of them are the biggest trees in the planet. There's one in India that can shelter 20,000 people beneath its crown because it's such a big tree.

PALMER: And yet as you say we are actually threatening these with our deforestation and also with climate change. How serious do you think this situation is?

SHANAHAN: Well, if you take it from the figs' perspective, this is just a blip in their huge huge huge timeline of existence. More pressing, I think, is our own vulnerability to the climate and our own vulnerability to other environmental issues. And the good news is that figs can help us address those challenges by helping us to reforest land that has been logged and helping us protect to the wildlife that sustains so many other species.

PALMER: Now, you say there are efforts underway to restore them to their natural habitats. Tell me a bit about those.

SHANAHAN: Well, in some places, people have been using fig trees amongst other plants to encourage other species to come in. So, with plants like figs, which grow fast, have strong roots and produce thick leaves and shade, the weeds can't grow, the figs grow very quickly and produce their figs in just a year or two, and this attracts lots of animals. This has been going on in Thailand where they have been reforesting parts of a national park that villagers had turned into agricultural fields. The forest is returning very quickly. Lots of wildlife is coming back. And in Rwanda and in Costa Rica, they're taking a different approach. They are lopping off huge branches several meters long from mature fig trees and just sticking them in the ground as instant trees, and again these trees are very quickly producing figs and soon after that, what will happen is other trees will populate the area because the animals that come to eat those figs will be bringing many other seeds.

Mike Shanahan (Photo: courtesy of Mike Shanahan)

PALMER: When it comes to restoring fig trees to their original habitats, what kind of technology are people using now for that?

SHANAHAN: Well, in Thailand, a biologist called Steve Elliott is exploring how to use drones to carry the seeds out into distant places and deposit them along with a little package of hydrating gel that will give them their best chance of starting out in life. These places are often quite inaccessible and it is difficult to carry trees that have been planted in a nursery up and down slopes and then bury them in the ground in faraway places. So, by using drones, this is how he hopes to accelerate the process.

PALMER: Mike, you talk about the secret history. What is the secret history?

SHANAHAN: Well, one of the secrets is the nature of the fig itself. For a long time, people thought it was a fruit, and for a long time people thought that fig trees didn't produce any flowers. And the secret is that actually, the fruit is not a fruit. If you look inside the fig, you'll find the flowers, and each of those flowers is capable of producing a tiny little fruit, which to our eyes looks more or less like a seed. In fact, it is a capsule that holds together all of this plant genus's power.

PALMER: Mike Shanahan is a freelance writer with a doctorate in rainforest ecology and the author of “Gods, Wasps and Stranglers: The Secret History and Redemptive Future of Fig Trees.” Mike, thanks very much.

SHANAHAN: Thanks for having me. It's been a pleasure.

Links

Gods, Wasps, and Stranglers: The Secret History and Redemptive Future of Fig Trees

Mike Shanahan’s blog, “Under the Banyan”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth