A Blueprint for $1 Trillion Infrastructure Spending

Air Date: Week of April 7, 2017

Successfully advocating for the high-speed Acela train, which began running from Boston to Washington, D.C. in 2000, was one of Michael Dukakis’s major achievements after his tenure as Governor of Massachusetts. (Photo: Ryan Stavely, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Trump administration promises a $1 trillion investment to rebuild the nation’s infrastructure, but has yet to offer design or budget details. Host Steve Curwood spoke with former Massachusetts governor and 1988 Democratic Presidential nominee Michael Dukakis offers a vision of rebuilt and expanded infrastructure, including national rail and public transportation.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

On April 3, a seemingly minor derailment at Penn Station in New York City led to monstrous delays affecting hundreds of thousands of people in the New York area and up and down the east coast. You see, like much of America’s infrastructure, the antiquated rail system at Penn Station is overloaded and under maintained.

The Trump administration promises to invest a trillion dollars to fix rails, roads, bridges, and transit, but so far it hasn’t put out any money where its mouth is. There is bipartisan support for infrastructure investment, and no one wants it more than former Massachusetts governor and Democratic presidential nominee, Michael Dukakis. Governor Dukakis now teaches at Northeastern University, and he’s a long-time advocate of public transit and a former Vice Chair of Amtrak. Michael Dukakis joins us now from Los Angeles where he’s a visiting professor at UCLA.

Welcome to Living on Earth, Governor.

DUKAKIS: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, in your view what's the state of the U.S. infrastructure right now?

DUKAKIS: It’s lousy and getting worse. While we're gonna spend another 60 something billion dollars on a military budget, which is already enormous and is financing a defense system involving 837 American bases in 150 countries, and we can't repair our bridges. I think that's crazy. I think this increase in the defense budget is crazy, and in the meantime the rest of the world is going right by us. High-speed rail, excellent highways. You go to other countries, it's a little embarrassing to come back to the United States.

CURWOOD: So, now, why did the American Society of Civil Engineers rate our national infrastructure at a D+? It's practically flunking.

DUKAKIS: Might be generous because we're not maintaining it. I don't think we need any more highways in this country. We need a very strong investment on public transportation and high-speed rail, especially in our cities.

Michael Dukakis, a longtime advocate for public transportation, has some thoughts and advice for Trump on his $1 trillion infrastructure plan. (Photo: Northeastern University)

You know, I mean, Greece has got an infrastructure that looks a hell of a lot better than ours these days. With all of its problems and all of its struggles economically, those highways are in superb shape. The metro in Athens is remarkable and probably better than any public transportation in any city in the United States. And that's true all over the world. Go to Spain. Not a wealthy country, but it's two and a half hours now from Barcelona to Madrid. Used to be four. Now it's two and a half, and in the meantime, we're standing still.

CURWOOD: Now, during the campaign, Donald Trump, the candidate, promised he would fix railroads, the bridges, airports, hospitals, roads, and now is promising to invest a trillion dollars in infrastructure. What could one actually do with a trillion dollars, do you think?

DUKAKIS: Well, let me begin, Steve, first by saying that Trump has never identified the money he's talking about. Look, this country is currently running a deficit of a half a trillion dollars at the end of the Obama administration, at a time when we're getting very close to full employment, and where we ought to have a surplus in the federal treasury. And he proposes not only tax cuts primarily for the wealthy, in the billions, but he's going to spend a trillion dollars on infrastructure. Where is going to get it? Infrastructure has been conspicuous by its absence in the first couple of months of this administration, and I don't think we have any present prospects for anything serious here, unless he's going to run a current deficit of a trillion dollars, in which case it raises interesting questions about whether or not this country can ever pay its bills.

You know, we did have a handsome quarter of a trillion dollar surplus when Bill Clinton left office, and in point of fact, if you will remember, Clinton, in his last State of the Union address, proposed a plan to reduce and eliminate the national debt in 10 to 12 years, and it was serious. And had Al Gore – Well, he was elected -- but had he in fact taken office, we today would have virtually no debt. Instead we have an $18 trillion dollar national debt. Under this guy, it's probably going to go to $20 trillion. Where's the money going to come from for infrastructure? I have no idea. I don't think he has any idea.

CURWOOD: If the money could be found, Michael Dukakis, what would be your top priorities for America's infrastructure?

DUKAKIS: A first-class, national, high-speed rail system and excellent public transportation, mostly rail-based, in the major cities in this country. Those would be my top two. I mean, the interstate highway system is pretty much completed now. It's got to be maintained, and that's important, but I’d begin with first-rate, modern, speedy ground transportation on rail in the nation's major metropolitan areas and, of course, nationally.

CURWOOD: By the way, the latest Trump budget zeroes out Amtrak funding.

DUKAKIS: That's correct.

CURWOOD: How much sense does that make?

DUKAKIS: None. None whatsoever and totally inconsistent with what he's been talking about. Point of fact, as you point out, in the campaign, he was talking about building our rail system. Amtrak is actually the national rail system which requires less subsidy than any other national rail system. Amtrak makes more of its money from the fare box than any other national rail passenger system in the world.

And yes, in point of fact, national rail gets subsidies, but think of the subsidies that highways get. I mean, think of these numbers. Right now, highways in America get something in excess of $40 billion dollars from the federal government every year. Air gets $16 billion. Amtrak is down to a few hundred million, and about 85 percent of its expenses are paid for by passengers and system revenue. That's pretty remarkable, and I don't think most people understand this. So, it's doing exceedingly well. On the other hand, we've got a new administration pledged to build our rail system, right? Pledged to fix our infrastructure and its budget, zeroes out Amtrak. Now, does the president know that? I don't know.

CURWOOD: What would a comprehensive high speed rail system cost in America, do you think?

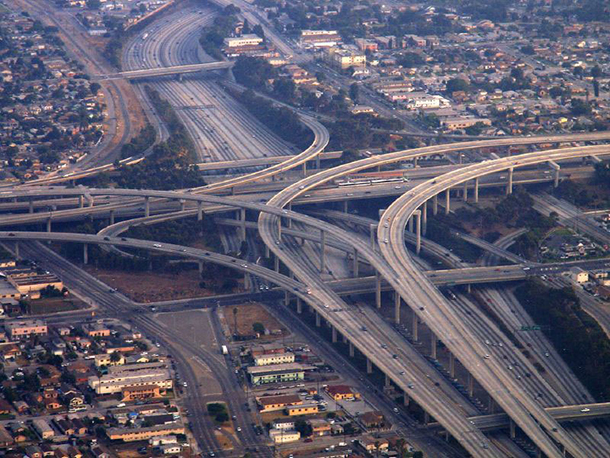

Interstate highways like these in Los Angeles dominate the transportation landscape in California. The city is currently focusing federal funds to improve the metro and regional connector systems. (Photo: Storm Crypt, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DUKAKIS: Well, when Barack Obama took over he asked for $10 billion to start it, and he got it from the first Congress, which, remember, was a Democratic Congress that first two years before Republicans came back and took it over. I would think somewhere in the range of $100 -$150 billion, but the states are deeply and actively involved in this. When the Obama administration asked for proposals from the states for that first $10 billion, Steve, they were overwhelmed. I think they got a $100 billion in requests. So, you're talking, I would think, in the range of $100, $200 billion and then a continual investment to make it better and better and stronger and stronger. But compared to what we're spending on the military, I mean, that's a rounding error.

CURWOOD: Michael, what about integrating rebuilding America's infrastructure with urban development and redevelopment? I'm thinking of better pedestrian spaces, bicycles, new vehicles such as driverless cars.

DUKAKIS: Well, that's part of it. But I think you can rely pretty heavily on states and local governments to do that kind of thing. And in point of fact, Steve, right now, here in Los Angeles, the voters of Los Angeles County have voted not once but twice to increase their sales taxes, to invest at long last in a first-class, rail-based transit system.

I just toured the so-called Regional Connector out here, which is a part of this major investment in transit, and it’s well underway. It's underground, at some point 100 feet underground. It will fully integrate and connect the entire Los Angeles transit system. And once that happens, in addition to major expansions of their transit system, this city is going to be one of the most impressive in the country, if not the world. And it's long overdue, needless to say, because the traffic situation here is horrendous. And a great deal of this is being financed by local taxes. On the other hand, it is getting some federal assistance, and that's pretty much the way these projects have been financed in the past. So, this partnership between the states and the local governments on the one hand and United States Department of Transportation on the other has worked quite well just as long as the feds are picking up their side of the bargain.

CURWOOD: Umm, Michael Dukakis, you were governor of Massachusetts for three terms.

DUKAKIS: Indeed.

CURWOOD: And famously, you rode the public transportation from your office on Beacon Hill out to Brookline where your house is, the Green Line in the Boston area. And, by the way, I think in that period of time, riders said that it ran better than before and perhaps after.

DUKAKIS: Dramatically so, they say. [CHUCKLES] But you'd be surprised at what you learn as a governor on the transit system. I mean, people would come up to me and say, "Hey, Governor, can I talk to you?" I learned more about what was going on in my administration on the street car than I did in the State House.

CURWOOD: And given your experience with Amtrak and the T, the MTBA in Boston. I imagine you've heard plenty of arguments against transportation infrastructure spending during your career. Talk to me about some of the most common challenges you've faced and what you would say to opponents right now.

DUKAKIS: I don't see the kind of opposition now, Steve, that we had 25 or 30 years ago, when we were still kidding ourselves that more and more highways could solve the problem. In fact, as you know better than anybody, we came dangerously close to building a kind of California-style freeway system in, on, and over the city of Boston, which in my opinion, would have destroyed the city. And you were there, reporting on this, when we had a 10-year battle over whether or not we would build a master highway plan. Fortunately, we stopped it, and then, thanks to a sainted man named Thomas P. O'Neill, Jr., who at that time was Majority Leader and soon became the Speaker of the House, we were the first state in the country to be able to use our interstate highway money for public transportation. It had never been done before. You couldn't bust the Highway Trust Fund, remember?

The Green Line is one of several light rail lines that make up the MBTA subway system in Boston. When he was governor, Michael Dukakis was famous for commuting on the Green Line to work at the Massachusetts state house in downtown Boston. (Photo: Jasonic, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

It was gasoline tax money. It had to be spent on highways. We were the first state to be able to break that and ended up with a big chunk of federal money, which had been allocated for highways, which made it possible for me to really invest heavily in what was a decrepit old transit system. I mean, I was riding streetcars when I first became governor that had been built in 1942, and we changed all of that, which just gives you some sense of what you can do when you have the resources to go out there and do stuff. But like everything else, you got to keep investing in it, and you got to have excellent managers.

But, I don't know of a mayor in the United States of America of a major city that isn't strongly advocating for major investment in his or her public transportation system. And Los Angeles is a good example of this. We've had two mayors, Antonio Villaraigosa and now Eric Garcetti, both of them strong proponents of investing in this new and very exciting, rail-based transit system out here in Los Angeles, and they're very typical of mayors all over the country.

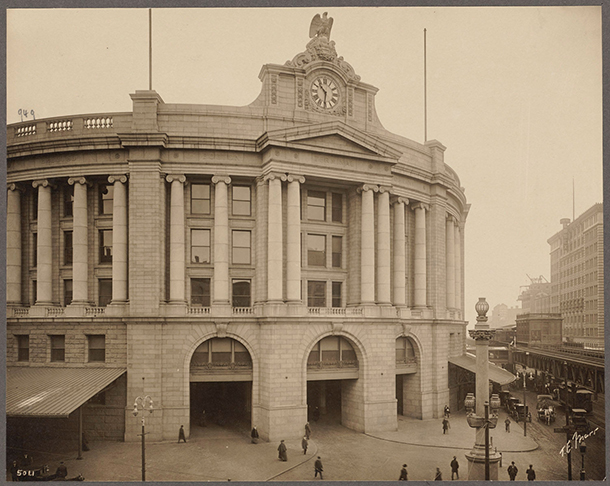

CURWOOD: You know, Speaker O' Neill, Thomas P. O'Neill, Jr., was famous for saying, “All politics is local”. And people listening to us may not know about the Boston transportation grid, but one of the things about Boston which is very odd when it comes to railroads, is that you could take a railroad all the way from Miami, Florida, to what's called South Station in Boston, but if you want to go on to New Hampshire or Maine, you've got to get out and go across town to the other railroad station. There's no link.

DUKAKIS: Right.

CURWOOD: I understand your latest project has been advocating for such a link. Why don't we have it? What do you think would be necessary to get it done as an example for the rest of America?

DUKAKIS: It was part of the so-called Big Dig plan which started with my first term in 1975, and that project was planned with a double rail line right down the middle of it. I mean, if you're going to rip up the entire city, that's the time to connect the two stations, right?

And, by the way, this is not a problem unique to Boston. You go to Paris, they originally had four railroad stations, right? And why? Because the railroads were run by private companies in those days, and every company wanted its station.

So, in Boston, New York-New Haven-and-Hartford wanted and got South Station. Boston-and-Maine then got North Station. Then there was this gap of a mile. I can show you legislative commission reports going back to 1910, ’12, ‘15 advocating for the connection. It didn't happen for a variety of reasons. Finally, I got elected in 1974, came in 1975. We started working on the Big Dig plan, and obviously, one of them was this double rail line right down the middle of it.

We then went to Washington, and the Reagan administration fought us tooth and nail on that project. Ronald Reagan actually vetoed the provision of the transportation law that would have financed the Big Dig. And, thanks to Tip [Thomas P. O'Neill, Jr], we had plenty of votes to override him in the House, but there was a real battle in the Senate, and for a variety of reasons we had to back off on the rail thing. After all, it was taking a precious lane for automobiles out of that project.

We did finally get two-thirds, so we proceeded with the Big Dig. As you know, it took too much time and cost too much money, but we never did the rail connection. Crazy. I mean think what it would do for the transportation system not only of metropolitan Boston but the entire northeast because we're talking about high-speed trains coming up to South Station as you know where they stop. Then you got to go over to North Station to get on the [Amtrak] Downeaster which takes you to Portland, Maine.

This is not unusual. You look at major cities all over the world. All of them have these 19th century stub-end stations, and they are all connecting them. In Europe -- Zürich, Stockholm, Malmo, Paris, of course. In Asia, you go to Japan, go to China, they're doing this on a regular basis.

From the archives of the Boston Public Library, the above photo shows Boston’s South Station, built in 1900. South Station connects Boston with New York, New Haven and Hartford by rail. (Photo: Boston Public Library, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Some people say the opposition to public transportation funding is the perception by many people that public transit is for "them", for somebody else. “I'm gonna to ride in my car and go exactly when I feel like it. So, if there's going to be public transit, it has to be for those people over there”. How common is this, and how does one confront this?

DUKAKIS: Well, I don't think it's a problem these days. I mean, go to New York. It's not just poverty stricken people riding their transit system. Everybody does. I mean, Los Angeles, get on the new Expo line and take a look at the people that are riding it. These are not poverty stricken people. I mean these are just folks that want to get from home to work and back again. I think we're by that one. I think now, it's a question of, are we prepared to do some serious planning and investing in the national rail passenger system and excellent metropolitan transportation systems? And I think we are.

CURWOOD: So, Governor, you're saying that sort of contempt for public transportation is now out of date, certainly among millenials living in the city, but how do you persuade the GOP to get involved?

DUKAKIS: Fortunately, there are a number of Republicans in the Congress that understand this and are very supportive of this, and it's been a bipartisan majority that has really supported transit and rail investments. And I think when all is said and done with this Trump budget, you will see significant support for Amtrak in that budget and significant support for public transportation.

CURWOOD: Including the Tea Partiers?

DUKAKIS: Not including the Tea Partiers, but the Tea Partiers for the most part don't represent districts that have major, urban, metropolitan areas. But fortunately there are 50 governors, all of whom are very concerned about transportation as well.

CURWOOD: So, when it comes to public transit, build it and they will come, huh?

DUKAKIS: Yes, if it's good, if it's well maintained, it's well managed, if it's clean, attractive, and that's what we're seeing in this city and that's what we're seeing in cities all over the country. We just need more of it. Do we need a stealth bomber which is going to cost us $300 billion, or might it make more sense to take that money and invest it in this country's infrastructure? I think the question answers itself.

CURWOOD: Michael Dukakis is a former Democratic nominee for President of the United States and former governor of Massachusetts. Thanks so much for taking time with me today.

DUKAKIS: Great to talk with you.

Links

NYTimes Editorial Board: “Missing: Trump’s Trillion-Dollar Infrastructure Plan”

American Society of Civil Engineers report card history

The Boston Globe: “State asks for bids in $2 million North-South Rail Link Study”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth