Unraveling the Myths and Mysteries of the Tides

Air Date: Week of May 5, 2017

High tide and low tide at Crosby, Liverpool, where the human figures of the modern sculpture Another Place disappear twice daily under the rising water. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

Tide tables report to the tenth of a foot the fluctuations of sea level as the ocean ebbs and flows. And though the moon has the greatest influence on tides, there’s much more at play. Now a new book, Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean, illuminates how they work. Mariner and author Jonathan White regales host Helen Palmer with the tale of a boating mishap that provided inspiration for the book, and the myths and history that roll in and out with the restless seas.

Transcript

PALMER: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Helen Palmer.

For the sailor, tide tables are a kind of bible that order your comings and goings. And mostly, sailors don’t stop to marvel at the heavenly powers that move the waters, even when they study the moon and stars on night passages. Now, there’s a book, "Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean", that melds science, history, and travel notes to explain the mystery of the tides, how humans have experienced and explained them, and what rising seas might mean for our relationship with our watery planet in the future.

Mariner Jonathan White was spurred to write the book when a tide caught him and his boat off guard.

WHITE: Well, I was actually in my mid 20s around that time when I got that big old wooden schooner, 65-feet. And we use to sail up and down the coast from Seattle to Alaska. And on one particular trip, we anchored in a small bay, and a gale blew up in the night, and I got up and noticed that something was wrong, and indeed we were aground at the end of the bay. We had dragged anchor.

PALMER: And what happened?

Jonathan White’s old schooner Crusader lists precariously as the tide rushes back in (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

WHITE: Well, I had been aground before, and if the tide was low, the boat would have come up, up off the mud, and no one would even have noticed. But as I studied the tide chart, I couldn't believe it because we were actually at the top of a high tide. And in Alaska they have large tides. So, what that meant was, in the next six hours, the water would go down 12 feet, and most of the water in this bay would disappear.

The boat went down and got stuck in the mud, so when the water came up it actually filled it with water, and by midmorning we were swimming through the boat. Everything started floating around. We had all provisions. Fruit and cookies and rice had swollen. We had a library of 300 books or so on the boat, and, if you've ever seen a book swell with water, you know that it gets three times the size and weight. It's actually a formidable weapon at that point. Some of the ironic titles that floated by that morning like, "Between Pacific Tides" by Ed Ricketts or "How Can I Help" by Ram Dass or "In Deep" by Maxine Kumin. It was quite funny at times.

PALMER: Long story short, you did in the end manage to get off, and you actually managed to refloat the boat and even restart the engine. But you're hardly the only mariner to go aground, of course. In the early days of exploration, there were many, many mishaps.

Author Jonathan White was inspired to write Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean following an experience when his schooner Crusader ran aground and flooded at the top of a high tide. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

WHITE: Oh goodness, eeven Cook in his explorations went aground in Australia in a very famous grounding where the tide went out and left them high and dry and, of course, they were used to very different tide regimes and didn't understand the dynamics of the tide in Australia which is typical of those days. The people were familiar with what happened around where they lived, but, once they went afar, they were quite often surprised. Where England and here has two tides today and, in fact, on the Atlantic coast as well, many, many places around the world have that. There are places like Tahiti that has one tide a day, and there are places that have four tides a day, and there are places that have six tides a day, and there are standing tides and double low tides and double high tides. So there are lots and lots of anomolies.

PALMER: Well, we all learn in school that basically it's the moon's influence that makes the tides. So, can you tell us how it is that the moon makes the tides happen?

WHITE: Yes, I'll start by saying it actually is the moon and the sun, but the moon because it's so much closer has about 50 percent more influence on tides. When the sun and the moon are working together, as they do during full moon and new moon, that's when we have our largest tides. But when the moon and the sun are at 90 degree angles to each other relative to the Earth, that's when the moon and the sun are working against each other, and we have the lower tides. It's called the neap tides.

So, when the moon is overhead and full, it's creating a bulge in the Earth's oceans underneath it, and we are actually spinning underneath that bulge. That's really how it works. There's a bulge facing the moon, and then here's another bulge on the opposite side of the Earth that's created by centrifugal force, which is the force we all experience when we come around a swerve driving, and what we feel is that the car wants to straighten out or flip over. Right? Well, that's generally why we have two tides a day.

Fishing boats at high and low tide in the Bay of Fundy, where the tidal range is a whopping 54.6 feet. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

PALMER: You spoke about the Earth spinning, and, indeed, as well as the sun's influence, there are also more influences of more weird phenomenon, like the fact that the Earth wobbles on its axis and, obviously, at some stages the moon is closer to us, and at some stages it's further away. All these play into the tides, which is why it becomes so complicated.

WHITE: Yes, that right. It's important to remember that everything is moving, and there's a gravitational relationship between all these parts. In general, there are over 400 of these relationships that affect the tide.

PALMER: Wow. You made me familiar with some wonderful words like “perihelium” and “perigee,” and my favorite of all is this word “syzygy.” S-Y-Z-Y-G-Y. It's wonderful.

WHITE: Yes, it's a great Scrabble word. It's a Greek word meaning “yoked together,” and it describes when the Earth, moon and sun are aligned. So, when we have our largest tides, it's usually because the Earth, moon and sun are aligned, and that's called syzygy.

PALMER: As I say, it's a great word.

You write about the vast differences in height between low and high tides, in some places as much 54 feet, yet the discrepancy is only about a couple of feet in, say, the Mediterranean. How does that come about?

WHITE: Well, the tide is a lot of different things, but you can boil it down to vibration and resonance, and resonance when something vibrates in response something else. So, when we talked about these four hundred different relationships from the heavens, right? Well, that's what's happening up there. What happens down here, is in a sense, the ocean basins of the world hear these relationships as if they were notes or beats or pulses, and the ocean basins, each one has a different kind of characteristic that responds to any one of those notes or calls from the heavens in a different way, and that's called resonance.

PALMER: Talking of the resonance in the ocean, you have a wonderful description of how they all interact with each other.

WHITE: Yes, I was walking through Oceanographic Institute with an oceanographer in the Bay of Fundy, a man named Charlie O'Reilly, and he said, "Well, it's like having a table, and if you fill the table with pans, all different sizes, shapes, some deep, some shallow, and then fill them with water e,ven at different levels, some all the way up, some just low, and then if you start kicking the table with the rhythm, right, and that kicking by the way is a force from the heavens. You know, again, it might be the full moon. And those pans will respond differently to the kicking. Some pans will be very excited, and some pans not so much. And then, you also have to remember, because they're touching, they also influence each other.

Low tide and high tide at Perranporth, Cornwall in the U.K. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

PALMER: It's a wonderful image because obviously you realize that the tide comes in and then it bounces off the shore and then maybe it hits another, maybe an island or it hits a reef or it hits the next continent.

WHITE: Yes, absolutely. There are vibrations that happen in Europe that find their way over, you know, thousands of thousands of miles, and they show up on another coast. That is absolutely true. The tide, you know it's a large wave that travels at 450 miles per hour around the Earth. When it hits continents, it reflects. It refracts. It folds back on itself. It slows down. It speeds up. I mean, it's mind-boggling how complex it gets.

PALMER: In your book, you write about the many scholars throughout history from ancient times who’ve tried to unravel these mysteries. How did the Enlightenment change our understanding of this given that this goes back to the Greeks and, indeed, I presume, to the Phoenicians and Babylonians too?

WHITE: Yes, for most of human history, 99 percent of human history, we had a very, very different view of the heavens. Right? We obviously observed it and, in fact, the earlier observers were called priests or astrologers, and they kept very precise information about the relationships of what was going on up there, eclipses and so forth, but they didn't know how it worked. They might look up at the moon and wonder, how does she do it? How does she reach out silently and invisibly over all that distance and stir the waters of the Earth?

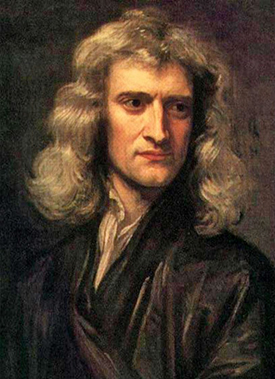

Sir Isaac Newton’s law of universal gravitation radically changed human understanding of the tides (Photo: Sir Godfrey Kneller, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

I mean nobody knew this. Right? But they speculated. I mean, some people thought the moon did it by heating rocks on the bottom of the ocean, and when those rocks were really hot, the water would boil and swell and that was high tide, and then when the moon went away those rocks cooled and that was low tide. And some people thought it was the breathing of a large beast or the breathing of the Earth itself. Even Leonardo da Vinci in the 13th century thought that it must be the breathing of a large beast, and he tried to calculate the size of its lung. Yeah, and on our coast, actually just up the coast where I am, High Tide Woman made the high tide by lifting her skirt.

And then, during the scientific revolution, culminating with Newton, we really radically changed that view of the heavens because gravity, until then, was just an inherent nature inside any object or person that caused it to fall. In fact, Keppler, the German scientist, said, “Gravity is soul. It's the soul of something that makes it want to go back to Earth.” It was the soul of the apple that made it want to fall.

And of course Newton changed all that and gave us the laws of planetary motion and gravity, and, again, that's when we started to get our foothold. But even Descartes, who is of course a French philosopher, a natural historian, they wanted to get away from gravity. You know, these new scientists wanted to leave the ancient world behind, and they couldn't stand the idea of gravity because it was this black magic, invisible force that did not fit with the new world, but in the end they reluctantly had to plunk it in the middle of their theory.

PALMER: Well, I have to say that gravity is still so mysterious that I can believe that there's a woman who lifts her skirts and that's how the tides come and go, just as easily as I could believe in gravity.

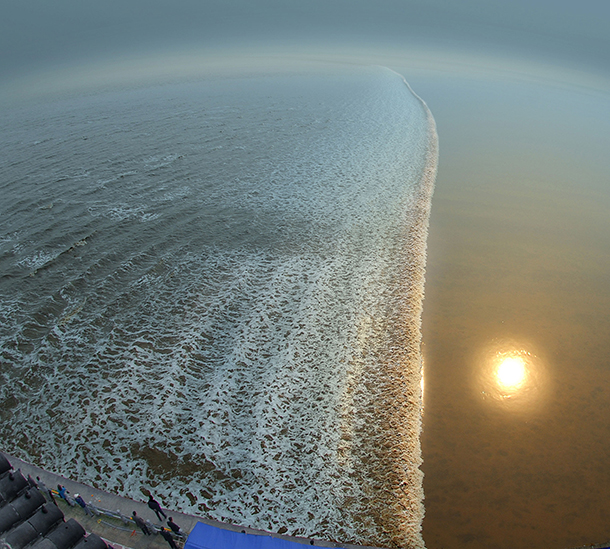

The tidal bore on the Qiantang River is known as Yin Long (Silver Dragon). (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

WHITE: Yeah.

PALMER: So, your book is quite a travelogue and an adventure story, quite apart from going aground. You follow surfers in search of monster waves, and you go in search of tidal bores. Tell me about tidal bores and the one you watched in China.

WHITE: Yes, that's a tidal bore on the Qiangtang River. And a tidal bore is when the tide comes up the river in the form of a wave or a solid wall of water. There might be 100 of them around the world, in the Bay of Fundy, up in the Cook Inlet in Alaska. The Amazon River has a large one. But the tidal bore on the Qiangtang River in China, which is just south of Shanghai in Hangzhou, is the largest in the world. It gets up to 25 feet tall, and it comes in on every tide, twice a day, every day. The first tide chart in the world that we know of came out of that place, and it was to log when the tidal bore showed up, and it was etched in stone in the 10th century, and it was probably a couple of hundred years before the first tidal chart appeared in the west, for the London Bridge in 1200.

PALMER: You've talked about these great tides, and I was actually struck that people in the past have used tides for power. I'd like you to read a passage from your book, please, if you wouldn't mind. It's on page 230. Can you explain the context for it?

WHITE: Yes, I think that people don't often realize how long we've been using tide energy actually. There were thousands of them around Europe, and on the east coast of the United States, particularly in the northern part there, we had hundreds of tide mills that started around 1620 and lasted all the way through the mid-1800s, milling lumber, and making paper, and fashioning copper.

And there is one tide mill, the oldest in the world, that is south of London in Southampton, actually, in the village of Ealing that is still operating. They still make flour. And I went there, and I got lucky. One of the tide millers invited me to help him with a tide cycle. And so, that's the context for this piece of writing.

[SOUND OF THE PAGE OF A BOOK TURNING]

The Eling Tide Mill building, with an old mill stone in the foreground and the tidal barrage (the wall with buttresses) visible. (Photo: Colin Babb, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

“Laboring at first, the wheel eventually rumbled to speed. The whole place seemed to come alive, creaking and groaning like a ship at sea. Windows shook. Iron latches and levers rattled. A spoon and pencil chattered in a jam jar. Upstairs, the grist bin’s tick-tick-tick confirmed that grain was being fed to the grinding stones. When I looked up from the swishing and gurgling water wheel, a stream of golden flour was pouring from the chute. The water wheel ran for four-and-a-half hours. Through the windows, I watched the tide disappear from the harbor, leaving all the boats aground. The mills wheel-wash gushed into the estuary like a whitewater rapid. A fine powder had the filled the air as soon as we started producing flour, settling on everything including our eyebrows and eyelashes. The place smelled like baking bread, hot grease, and low tide.”

PALMER: It's a wonderful bit of writing. It's wonderfully descriptive.

Finally, we know that sea level is rising due to global warming, so what can we expect from the tides in the future, or do we just not know?

WHITE: There's a lot of that we don't know, but we do know that, if sea level rises three feet in the next 50 years, which is a conservative estimate, there will be a lot of people and communities that will have to move. And I think one the things that is important to understand is that sea level isn't level. I mean, we're taught in kindergarten that water seeks its own level, and it may, but it doesn't find it in the ocean.

For example, where I live on the Pacific, the trade winds push the water across the ocean westward and it piles up in Asia, in the South Pacific. So, that level over there is two feet higher than it is against my coast, and the Pacific is about a foot higher than the Atlantic, and the Atlantic slopes from Florida up to New England. Also, we know that land is changing. Right? Some land is rebounding from the last glacial age, lifting, and some land is sinking. The tides happen on top of all that. And, if we harken back to that conversation about resonance, as the sea levels change, it changes the basin's natural frequency of vibration. So that's where we're going to have the major changes in tides, and we could see larger tides in some places, and, in fact, we could see lesser tides in others, as sea level rises.

Author Jonathan White is an avid surfer and sailor. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

PALMER: Jonathan White is a marine conservationist, sailor, surfer and author of the book "Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean". Thanks very much for spending time with me today.

WHITE: Thank you, Helen. I really appreciate it.

Links

Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean

LiveScience: “What Causes the Tides?”

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Tides & Currents

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth