African Dams Dry Up Wetlands & Local Jobs

Air Date: Week of January 5, 2018

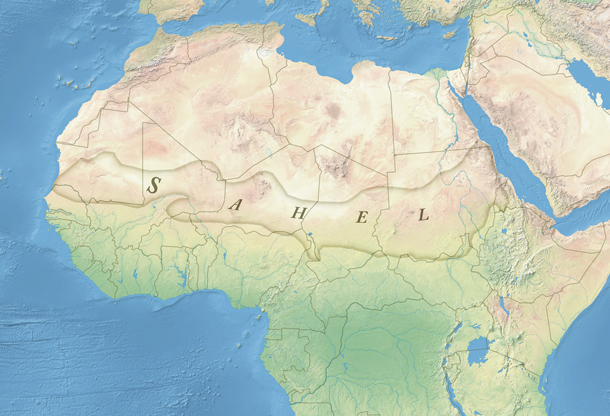

As dams divert water from downstream and stop seasonal floods, farmland dries up in the Sahel region of Africa. (Photo: IFPRI/Milo Mitchell, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Dams in the Sahel of Africa can provide power and flood control, but the absence of seasonal floods is changing wetland environments and wrecking the livelihoods of people who depend on them. Journalist Fred Pearce connects the dots with host Steve Curwood from dams to parched wetlands to fishermen with no work, to desperate people leaving for Europe or joining terrorist groups like Boko Haram.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Large dams often draw scrutiny for their impacts on the local habitat, from fish stocks to plant life. But they can also disrupt society, rendering traditional livelihoods obsolete in the name of economic development. Writing for the online publication Yale Environment 360, journalist Fred Pearce describes how the loss of wetlands is helping fuel Africa’s migrant crisis. He joins me now from London. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

PEARCE: Thank you. Good to be there.

CURWOOD: Fred, first describe to me what’s happened to the wetlands in the Valley of the River Senegal where you've done a lot of reporting.

PEARCE: Essentially, they're drying up. Back in the 1970s, 1980s, at least I'm old enough to remember that we had a series of massive droughts in Africa, famines and so on in Ethiopia right across West Africa. And in that time governments decided they wanted to set up irrigation projects, and they also started to dam the main rivers in the region for hydroelectricity. They wanted to make more economic use of these rivers, and they hoped to maintain them in dry times. But there have been a series of perverse consequences of damming of the rivers. The worst of them has been the loss of the wetlands that the rivers in full flood used to fill every year. The water is now held back behind dams, the flooding simply doesn't happen anymore. And what has been forgotten I think is that millions and millions of people are dependent on these wetlands. There are some two million people in the inner Niger delta. There are probably 10 million people in and around Lake Chad and along the flood plains of the rivers that used to fill Lake Chad. And with water being held back, the result for these people has not been more prosperity, but a loss of the basic natural resources on which they rely. So there are no fish in their lakes. The old system of irrigation which relied on planting crops in the wet soil as the annual floods retreated -- there are no wet soils now to plant crops in.

Similarly, pastoralists used to, and still do to some extent, bring their cattle from all across the region to these wetlands. They are the last green parts of the Sahel during the dry season of the year. If these areas are no longer wet, the cattle have nowhere to go. So, whole series of livelihoods based around fish and climbing and nomadic cattle herding have been seriously damaged. People simply don't have livelihoods anymore.

Lake Chad from 1973 to 2017 (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory)

CURWOOD: No way to make a subsistence living; what's happened to people?

PEARCE: Well, they're simply moving out. To start with, people are moving to the capital cities of their countries, to Bamako in Mali, to Dakar in Senegal, and other major urban centers to look for work. Now, people have always done that but they used to move backwards and forwards. You do that in a bad drought season and then go back to your fields and your pastures when the rains return. But these days with no water coming down, people are leaving for the cities for good, but increasingly making international migrations. Increasingly, people have been taking people smuggling routes across the Sahara desert into Libya and then taking very dangerous boats to try and land in the European Union, in Italy or sometimes in Greece. So, people are taking desperate steps to try and find a better life.

CURWOOD: What has this done for political stability in the region?

PEARCE: Around Lake Chad it's extremely bad. You probably have heard the stories of the Islamic terror group Boko Haram in that region, which famously kidnapped more than 100 schoolgirls a couple of years ago, and there have been a huge number of other atrocities. Essentially the region around Lake Chad is now a no-go area, particularly in Nigeria. And the reason for this is really a social breakdown, because people without resources have been moving around, looking for somewhere else to go. People who once fished in Lake Chad -- well, their fishing villages are now tens of kilometers from where the water is -- so they're moving on looking for somewhere else to go, landing up in refugee camps.

Fishing in the Sahel region has become much more difficult as dams have restricted flow to rivers. (Photo: Carsten ten Brink, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

And of course, militant groups take advantage of this, take advantage of the dislocation of young people and the sort of breakdown of the law and order that follows from this, and we're having a wider breakdown of law and order in which millions of people are homeless and many of those homeless people are just shipping out all together. So, I wouldn't say the social breakdown is all because of environmental issues. There are a lot of other social factors involved. But the breakdown of the environment is undoubtedly contributing to a breakdown of the law and order, and the rise of Islamic groups, and partly as a result movement of people out of the area. They just don't want to live there anymore.

CURWOOD: Fred, in the course of your research I know you talked to a number of people. Tell me an anecdote of a migrant who was caught up in this.

PEARCE: Well, let me give you, give me two anecdotes. I met people on the shores of Senegal in West Africa, people who used to be fishers on the river Senegal who found that there were no more fish in the river. So, they moved to becoming ocean fishers, and they used to take their boats out into the coastal waters along Senegal, a rich fishing area. And then they found that European trawler boats had moved into this area. The national government had sold fishing rights to European trawlers, and there were many fewer fish. So, I met one, one day who'd just been picked up by the local police because he'd been trying to get on a boat and take his boat to the Canary Islands way out in the Atlantic territory owned by Spain because he wanted to move to Europe. So, he had made a clear progression. The rivers weren't delivering fish, so he went to the ocean. The ocean wasn't delivering fish, so he was going to get out, and he was going to go to Europe.

Manantali Dam in the Senegal River basin (Photo: Benoît Rivard, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

And along the Senegal River Valley, I've met many people in small villages where they told me that most of the community of those villages had left. There were a few people around, but not many. I met schoolteachers and farmers and pastoralists, middle aged men who told me, “You know some of my friends in the last few years have left and they're now phoning me back from Europe and saying they’ve got money now, they’ve got jobs, they're making a go of their lives, some of them have become university graduates, and I'm stuck at home still trying to fish in the river, still trying to look after my cattle, and I'm dirt poor. So, next year I'm going too”. These are the stories about real people trying to live their own lives. They are not victims in the sense that they have no resources, no possibilities. They're not heading for refugee camps. These are regular people in small rural communities who are thinking about their lives and the lives of their families and their children, and they're thinking, “What are we going to do, how are we going to react to the new situation in which we find ourselves?” More and more of them are saying, “I'm going to take my life into my own hands. I'm going to either migrate myself or tell my children to get out of here”.

CURWOOD: Fred, how much of the drying up of the wetlands is the result of climate change versus humans interfering with river flows?

PEARCE: It has very little to do with climate change at this point. We had some dry years in the 1970s and 1980s, but since then rainfall has largely recovered. You can't blame the low flows in the rivers or the lack of water getting into critical wetlands -- you can't blame that on climate change. This is a result of decisions taken about damming rivers to hold back water for other purposes, decisions often taken in response to the droughts of past years. But as it has turned out, they have made things worse in many rural communities.

A street scene in Burkina Faso, in the Sahel region of Africa. (Photo: Adam Jones, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: So, to what extent are development agencies looking at this issue, looking at the value of the wetlands vis-à-vis the possible gain from putting these dams in?

PEARCE: They've taken the same view of the national governments in Africa that they want economic development in a kind of western form of delivering money for national exchequers, measurable international trade in goods. The trouble is, much of the wealth that comes from wetland is never kind of monetized. It happens way out in the bush. Lots of people with subsistence livelihoods or trading in rather traditional manners in fish across the region -- I've seen that. And that kind of never shows up in national statistics and I think governments ignore this and I think aid agencies have been guilty of ignoring this. Not all. Some groups, the Red Cross talks about these issues, Oxfam and some others talk about these issues, but it has kind of been forgotten because this kind of economy, this basic economy for rural people doesn't show up very often in national statistics, and I think increasingly in development community it's now realized that some really bad decisions were taken. And I think environmentalists have been guilty too. Environmentalists have traditionally seen wetlands as places where it's great for bird life, fisheries and so on. So, they look at it from a wildlife perspective. But the point that millions of humans also depend on these wetland environments has kind of fallen through the gaps. The development agencies didn't think about it, governments didn't think about it, and even environmentalists who probably knew more about these wetlands than most outsiders, even they were ignoring the human consequences of their drying up.

CURWOOD: Now, Fred. Talk about some of the possible fixes here. What about a massive release of water now and then to mimic a flood? This technique has been used, for example, here in the United States on the Colorado River.

PEARCE: Yes, indeed you can do it, and for a short term, it will work. But in practical terms it's not often been very successful. You have to think about who built hydroelectric dams. What was the purpose of these dams? If they were built to provide hydroelectricity, then the people in charge of the turbines, the people in charge of the sluice gates, are the people generating the electricity. So, while you might have a release one year, the practical experience is that after a couple of years that doesn't happen. So, in Cameroon some of the rivers that flow down into Lake Chad, people 15 years ago were making a big point that people on the river floodplain were losing out and the government got a bit interested in this. For a couple of years they put in an artificial flood, if you like, and they released water during the natural flood season, and that was beneficial. And then it was a pilot project and the pilot project ended and nobody carried on, even though the benefits for the downstream communities were clear.

The Sahel region of Africa (Photo: Munion, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Fred, what you described sounds like an epic disaster in slow motion. Who's pushing back against this? Who is advocating for those people who have subsistence livings based on these wetlands?

PEARCE: In every country I went to, I found government officials, but also NGOs and other people within the countries arguing very strongly for the kind of things that I say, pointing out the value of wetlands and the importance of providing water down rivers to maintain wetlands, for instance. So, it's not as if nobody knows, it's not as if nobody cares. The problem is these messages kind of get lost as they go up the decision chain, so that it is harder to get those ideas across to the people who run the hydroelectric dams, to the people who are the government ministers. There are international agreements which talk in general terms about the sustainability of wetlands and protecting livelihoods and that kind of thing, but when you get from those abstract words into the real nitty-gritty of what you do on a river, the message again seems to get lost and you know, there are urban priorities that are rather different from rural priorities. And urban priorities, not just in Africa but in most of the world, have greater force and are heard more loudly. Trouble is, of course, in much of West Africa or in Central Africa most people are still in the countryside whereas most of the decision makers are in towns.

CURWOOD: Fred Pearce is an author and journalist based in London, and a contributor to Yale E360. Fred, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PEARCE: Pleasure, thanks very much. I enjoyed it.

Links

Yale E360: “How Big Water Projects Helped Trigger Africa’s Migrant Crisis”

The New Yorker: “Lake Chad: The World’s Most Complex Humanitarian Disaster”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth