Babysitting Arctic Terns

Air Date: Week of January 19, 2018

Arctic Tern in its nest. (Photo: Nathan Graff / USFWS, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Arctic terns undertake the longest known migration on earth, travelling more than 50,000 miles per year. But reduced habitat threatens nesting sites. Gwen Potter is a countryside manager at National Trust, a British conservation organization. She tells host Steve Curwood about their tern babysitting endeavor that helped dramatically increase the number of fledglings on the Northumberland coast.

Transcript

[CALLS OF ARCTIC TERNS]

CURWOOD: In the Christmas Bird Count, it’s not just the local resident species that are tallied, but the birds of passage too. So if you happen to live in the right latitude, you might get to add in the arctic tern. They’re rather ordinary black and white shore birds, with bright red beaks. But they are champions of migration. In fact Arctic terns travel as much as 56,000 miles a year, which is the longest known migration on earth. To give them some help conservationists work hard to protect part of their breeding habitat on the east coast of England, just south of Scotland. Here to tell us more is Gwen Potter, she’s the Countryside Manager for Northumberland Coast and Farne Islands at the National Trust, a conservation organization.

National Trust purchased more than two hundred acres of shoreline to protect habitat for breeding Arctic terns. (Photo: Kate Bradshaw)

POTTER: They are the most graceful birds you could ever imagine. So, they have this incredible white and gray color and they just kind of float through the sky and twist, and in the start of the breeding season, they like to play with each other in the sky, and they'll fight each other off, and they have these beautiful forked tails as well. So, they're quite often called sea swallows, and they’re just the most wonderful birds to see. And they're very, very angry, Arctic terns. They like to attack people when they - when people approach their nests. So, they've got a lot of character as well.

CURWOOD: Your organization has bought up some 200 acres of land to protect that breeding habitat for them, and you have sort of set up a round the clock babysitting service for them. Why and what did that entail?

POTTER: We already have an area of land that we look after for these terns, and we now have a bigger area that we can protect which is absolutely fantastic. So, we've basically doubled the area that these terns would potentially be nesting in. So, the idea will be to close off some of these areas in the summer months to allow those terns to come in and nest on the sand and that way we’ll be able to keep an eye on the them around the clock. We’ll be living in the dunes nearby, and we'll be checking up on them 24/7.

Arctic Tern eggs. (Photo: Mike Beauregard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, I understand in some of your protection of these birds, you actually end up relocating nests. How does that work?

POTTER: We do. When there is a very high tide, we move the nests onto fish boxes filled with sand, and that just raises them above that water level. It is something that is quite risky because obviously you think, I'm interfering with the nest, it might create an issue. But it's a tried and tested method. Eighty percent of the time it's successful and, ultimately, if we didn't do that, they would simply be washed away.

CURWOOD: So, what are the risks to the terns there as they are nesting?

POTTER: In the daytime, it's generally humans, people. So, if people walk through and they don't see the eggs, and they don't really know where they're going, they can cause a lot of disturbance. If they get too close, quite often they'll get attacked by the birds, so they'll very quickly realize that they're not supposed to be there. It's quite scary for them, but in the meantime, what will happen is the birds will be off their nests all of the time, and then they're leaving their eggs behind. Their eggs will chill, and they won't survive. In the night time, it tends to be predators coming in, so we'll have all kinds of different species that will come in and try and take eggs and then they'll try taking the younger chicks. We do have one more risk, which is people actually stealing eggs.

CURWOOD: People stealing tern eggs? Why?

POTTER: So, it's something that people used to do in Victorian times, they just used to collect eggs, and it's a bit like stamp collecting. And there are people who for very, very rare species will spend huge amounts of money on acquiring some of these rarer eggs.

CURWOOD: So, what are your results? How many terns were able to successfully breed there and how does that compare to previous years?

POTTER: We had a slightly higher number of Arctic tern pairs last year. But the number of fledglings that they produced, so the number of birds that successfully went on to become adults, went from two to 479. So, the previous year in 2016, it was two and then it's gone up by a very large number, which is fantastic news.

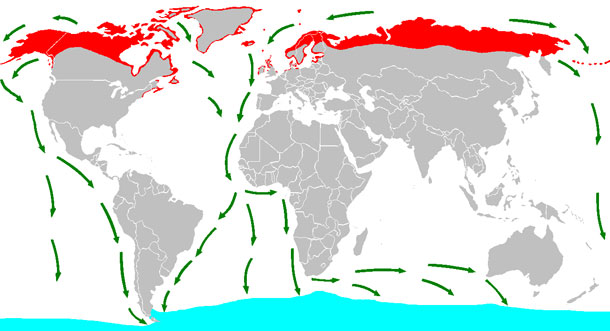

Arctic terns migrate from breeding grounds in the far north (red) to the Antarctic for summer in the southern hemisphere (blue). (Image: Andreas Trepte, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.5)

CURWOOD: Wow! So what do you attribute that to?

POTTER: In all honesty, it's weather. So, we do as much as we can to protect these birds, but quite often the weather can cause huge issues because they live on the tideline. If there are increased numbers of -- such as extreme tide, the eggs are washed out. And we had slightly better weather in most recent years. Over time what we have seen though is that we do have increasing numbers of really severe weather events that will impact on these nesting birds. So, we're looking but in the long term, we will have more extreme tides which can impact some of the time in localized areas as well.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, once those Arctic terns take off that's when their real work begins. Tell me a bit about their migration pattern.

POTTER: It's a most wonderful thing, yeah. They've got a bit of a job. They basically go to Antarctica from here in Northumberland, and when they reach Antarctica, they'll spend quite a lot of time essentially flying the southern oceans to Australia and New Zealand and back in between around Antarctica and right back up to exactly the same place where they originally nested. So, that's the equivalent of flying twice around the circumference of the globe. And they're seeing more daylight than any other bird because they're spending all of their, our winters down in the Antarctic where it's now sunlight almost 24 hours a day.

CURWOOD: So, among all these Arctic terns that buzz around the planet to the tune of nearly 60,000 miles a year, any one of those critters that’s attracted your attention for one reason or another?

POTTER: We do have a couple of birds that actually some of the terns kind of nest on the roots where we're actually going to move these boxes, so they will quite often attack you, particularly at the beginning of the season. They get very, very angry when you go past them. So, what they'll do is swoop down, they’ll peck on your head, they'll also poo on your head as well, and so those particular ... and they are the birds that come back every year. So we know number 23 is back, fantastic. You know what's going to happen when we go down and look at the boxes! [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Number 23 is apparently full of it, huh?

POTTER: [LAUGHS] That's right.

CURWOOD: Gwen Potter is the Countryside Manager for the Northumberland Coast and Farne Islands at the National Trust which is a British conservation organization. Gwen, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

POTTER: Oh, thank you it was really good to talk to you. Thank you.

Links

About the Arctic Tern from The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth