A Waddle of Penguins

Air Date: Week of March 23, 2018

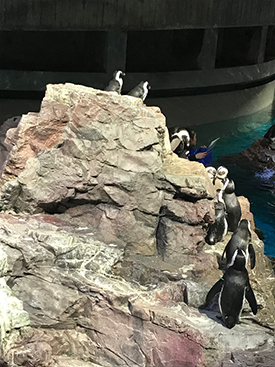

On land, a group of penguins is called a “waddle”; a group of penguins in the water is a “raft." (Photo: David Cook, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

Researchers recently spotted a supercolony of some 1.5 million Adelie penguins on the aptly named Danger Islands in Antarctica with the use of satellite technology. Host Steve Curwood discusses the significance of this discovery for the Adelie population with P. Dee Boersma, conservation biologist at the University of Washington, and asks why she and many other people find these birds that fly through water so irresistible.

Transcript

[SOUNDS OF JACKASS PENGUINS AT AQUARIUM]

CURWOOD: These Jackass penguins live at the New England Aquarium -- where Living on Earth’s Savannah Christiansen and Aynsley O’Neill took a penguin field trip and found Little Blues –

[CALLS OF LITTLE BLUE PENGUINS]

CURWOOD: and RockHoppers –

[CALLS OF ROCKHOPPER PENGUINS]

CURWOOD: and lots of penguin fans.

CHRISTIANSEN: Are you guys fans of penguins?

DILLON: Yea.

CHRISTIANSEN: Why? Why do you like penguins?

ALEX: They’re cute, I don’t know -- they’re entertaining.

CHRISTIANSEN: What if we told you that they just discovered a super colony of 1.5 million penguins that they didn’t know existed before, what would you guys say to that?

ALEX: I would want to go and see them.

CHRISTIANSEN: Why do you like penguins?

ELLIE: Cause they’re soft! Because this one’s soft.

MOM: That one’s soft? Do you like to watch them swim fast?

ELLIE: Yes swim fast!

MOM: Hey Daniel, why do you like penguins?

DANIEL: Cause I just do!

MOM: You just do?

DANIEL: I like to feed penguins.

MOM: Oh you like to feed them?

An Adélie penguin, easily identifiable with its simple black-and-white coat and button eyes. (Photo: oliver.dodd, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CHRISTIANSEN: What would you feed them if you could?

DANIEL: Fish! Yum yum yum.

CHRISTIANSEN: Why do you like penguins?

ISABELLA: Because they’re wicked cute and they’re my best friends favorite animal.

MICHAELA: Because they’re fun to look at, how they, like, swim and do funny stuff and talk to each other.

JACKSON: Cause they’re so cute.

CHRISTIANSEN: If you guys could have a penguin would you own a penguin as a pet?

ALL: Yea!

CHRISTIANSEN: What would you do with your penguin?

ISABELLA: I would put it in my pool.

MICHAEL: I would bring it to the beach.

JACKSON: I will bring mine to a beach too.

CURWOOD: Well, as much as people like them, several species of penguins are now listed as endangered or vulnerable. So the recent discovery of a super-colony of some one and a half million Adélie penguins in Antarctica is great news, especially for scientists who study these birds that fly through water. And none is happier than University of Washington conservation biologist Dee Boersma. Welcome to Living on Earth, Dee!

BOERSMA: Well, thanks very much. It's nice to be on.

CURWOOD: So, tell me about the Adélie penguins. What are they like?

BOERSMA: The Adélie penguin is the perfect penguin. People see it on public television. They're the black and white ones, and they look like they have button eyes, and of course, they're so well feathered because they live in Antarctica, so they have feathers that go down to the opening of their bill where they can breathe, and they're beautiful black and white, and not very tall. They're just about the size of a good stuffed penguin toy, so they're about a little over a foot high, and they were actually named Adélie penguins by a French explorer. His wife was named Adelie or Adélie, and so that's how the penguins got their name. So, he must have been in the Antarctic a long time really missing his wife.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I guess so! By the way, where are penguins evolutionarily speaking?

BOERSMA: Oh, they're old. They're from like the Miocene, you know, like 200 million years ago. So, they used to have penguins that are now extinct that were as big as people, so some of them weighed like 200 pounds and they got to be five foot four, but now the biggest penguin we have is the Emperor penguin and that's the one that's featured in the film "March of the Penguins."

Jackass penguins at the New England Aquarium gather around during feeding time. (Photo: Aynsley O’Neill)

CURWOOD: So, what exactly is a super colony?

BOERSMA: It's a lot of penguins. Most of the time, I mean, penguins are colonial, but usually they live in fairly small colonies depending on the species and sometimes they –they may not even live very close to each other. But Adélie penguins, they live very close together and they make their little nest out of rocks that they collect and deposit. So, a super colony means you got a whole heck of a lot of Adélie penguins. Most of the colonies might have a few thousand penguins, but a million penguins, well, that's a really big colony.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now, how did researchers come to find these penguins, this huge population?

BOERSMA: Well, it is incredible to find 1.5 million penguins that you didn't know about, but that's really the wonders of technology. Technology is allowing us to see things that we couldn't see before, and in fact, Heather Lynch found double the population size of Emperor penguins by using, again, this satellite imagery. And of course, satellites, they provide us our weather and in this case they're providing a satellite data so that we can find these new colonies of penguins, and if you look at the satellites you can see where the penguins are because they eat a lot of krill which are just shrimp, and so when they poop, it poops pink, and if there's a big colony of penguins you see a lot of pink poop. And then you have to go on the ground and find these places, and then you can see the penguin. But that's the wonders of the technology because you can do it from space.

CURWOOD: Now, how common are discoveries like these?

BOERSMA: Well, really rare. I mean, it's just because of the change in technology.

African penguins, also known as jackass penguins, at the New England Aquarium. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about where these Adélies were found. What kind of territory is it?

BOERSMA: Well, it's well named ... in the Danger Islands, [LAUGHS] so you wouldn't want to go there as it's dangerous. So, that's where they found it.

CURWOOD: Now, the Danger Islands what kind of protected status does this area have now that we know about this penguin super colony?

BOERSMA: Well, most of these areas don't really have very much protection. There is a new marine protected area in the Antarctic. The Antarctic, of course, is protected by the Antarctic Treaty, of which the United States is a signatory, and so are many other countries. That's why we have all these bases in the Antarctic.

CURWOOD: So, as I understand it then, these Danger Islands are, well, they're not protected. People could go, kind of do what they want to do.

BOERSMA: You could, but good luck. I mean the Danger Islands are well named, so there's all kinds of rocks and things there, and there's ice. So, you would have a heck of a time.

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about the Emperor penguin discovery. Where and just how many there?

BOERSMA: They doubled the number of colonies of Emperor penguins known. So, that's the thing. When you find 1.5 million penguins or double the number of colonies known for a species, it certainly changes your view. But it probably doesn't change the trend because, of course, we're interested in trends and what's happening to penguins, and when you find a lot more when you think that they're really rare then that's really good news because then you know that they're not in as much trouble as you thought before. I mean, suddenly there's more penguins than we thought for some of these species, so that's good news, but it doesn't mean that the trends have changed, it has just bought us more time. So, we hope that some of these species of penguins don't continue to decline.

CURWOOD: Now, what does all this mean for the conservation of penguins?

BOERSMA: Well, it means that we're in better shape. I mean, of course, the Adélie penguins, they are considered of least concern because there are so many of them, but the nice thing is a few years ago they were considered near threatened. But now that we’ve found these new colonies, now we say they're at least concerned because there's you know million more Adélie penguins than we thought before, so that's the good news.

Mating Adélie penguins at Cape Adare in Ross Sea, Antarctica. The supercolony on the Danger Islands has over 750,000 breeding pairs. (Photo: Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Professor Boersma, what can be done to ensure the global survival of penguins?

BOERSMA: Well, there's a lot of things that individuals can do. Part of it is your food choices. If you're going to eat anchovies on your pizza, great, eat anchovies on your pizza, but don't eat farm-raised chicken that are fed anchovies, or farm-raised salmon that are fed anchovies. All of those things take food away from penguins.

The other thing we can do is make marine protected areas, so that there are some places where the fish are protected so that the penguins can thrive and the fish can reproduce in there and then they can go out from these marine protected areas and reproduce in other places, but we need to have reserves to be able to protect fish, penguins and other species.

CURWOOD: By the way, why are you so fascinated with penguins?

BOERSMA: Well, it's hard to find people that aren't. They walk upright, they're curious, they're cute, they're industrious. I just don't think there's anything not to like about penguins unless you're trying to grab ’em, and then they bite you and then there's a good reason not to like them, but of course, they don't want to be grabbed.

CURWOOD: And I know you are a scientist, but come on, you can tell us your favorite.

BOERSMA: Well, you know, that's really hard. I've spent 45 years of my life working on Galapagos penguins and now I just finished season 35 working on Magellanic penguins in Argentina. So, I really like penguins, but what's more important to me are really long-term studies because long-term studies really inform us about our world and what other creatures are facing as well as humans.

CURWOOD: When did you first meet a penguin?

BOERSMA: Ahh Jeez. A long time ago. I guess it would be 1970.

CURWOOD: And what did you think?

BOERSMA: I thought that was one of the most interesting coolest things I had ever seen. I met a Galapagos penguin and I thought, gee, “What's a penguin doing living on the equator?” I thought it was just crazy. They've never seen an ice flow in their life, but I just I found penguins fascinating and clearly, after 45 or so years I still find them awfully interesting.

Professor P. Dee Boersma, with Magellanic penguins at Punta Tombo in Argentina. (Photo: P. Dee Boersma, University of Washington)

CURWOOD: I spent some time around Cape Town and the so-called Jackass penguins there.

BOERSMA: And you know why they're called Jackass? They're call Jackass because the first explorers were camping out and they thought they were surrounded at night by donkeys and when they got up in the morning there were no donkeys. There were just penguins, and hence the name Jackass penguins.

[SOUNDS OF JACKASS PENGUINS]

CURWOOD: Because they make that noise, that braying noise.

BOERSMA: Yeah.

CURWOOD: They're very smart though, those penguins.

BOERSMA: Right. Now penguins are not dumb, they would've gotten this far if they were. They know how to get along in our world to some extent. We just got to give him a little space, so they can.

CURWOOD: But what is their secret to always having the tuxedo completely neatly pressed?

BOERSMA: Well it's not. If you look in Antarctica or even at Boulders Beach where you were in South Africa, many of them look pretty muddy depending on the day and stuff and they can be covered in poop. And so, their secret is they go to sea and wash off and then when they come back they look like they just came from the dry cleaners. They're really well dressed and well pressed.

CURWOOD: Penguin expert Dee Boersma teaches at the University of Washington. Thanks so much for taking the time today, professor.

BOERSMA: It is my pleasure. It's always great to talk about penguins. I hope everybody helps save one.

Links

The Center for Ecosystem Sentinels was founded by Professor Boersma

Special thanks to the New England Aquarium for their penguin calls and visitor testimonies

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth