Coal Plants Damage Infant DNA

Air Date: Week of March 30, 2018

China has relied on coal to carry it through its rapid industrialization, but some plants are shutting down as China makes moves toward renewable energy. (Photo: Azchael, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

Coal plant emissions can damage health in many ways and new research suggests that they can have direct impacts on genetic fitness. The study from Columbia University found notable differences in the DNA of neonatal babies born before and after a coal plant in China was shut down. Host Steve Curwood spoke with co-authors Dr. Frederica Perera and Dr. Deliang Tang about coal pollution’s effects on long-term physical and cognitive health outcomes.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Pollution from coal plants has been linked to adverse health effects, including increased risk of cardiovascular problems and shortened life spans, and a new study suggests a reason why. Telomeres are protective tips at the end of each string of DNA, and if they shrink they make it harder for cells to reproduce properly. And it’s known that shorter telomeres are linked to aging. Now researchers at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health have found that babies born near a coal plant in China had shorter telomeres than those born in the same place after the plant was shut down. Two of those researchers from the Mailman School – Professors Frederica Perera and Deliang Tang join us now from New York to discuss their findings – welcome to Living on Earth!

PERERA: Thank you very much.

TANG: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, perhaps, Dr. Perera, you could explain the function of telomeres. What are the health effects related to shorter than average telomere lengths?

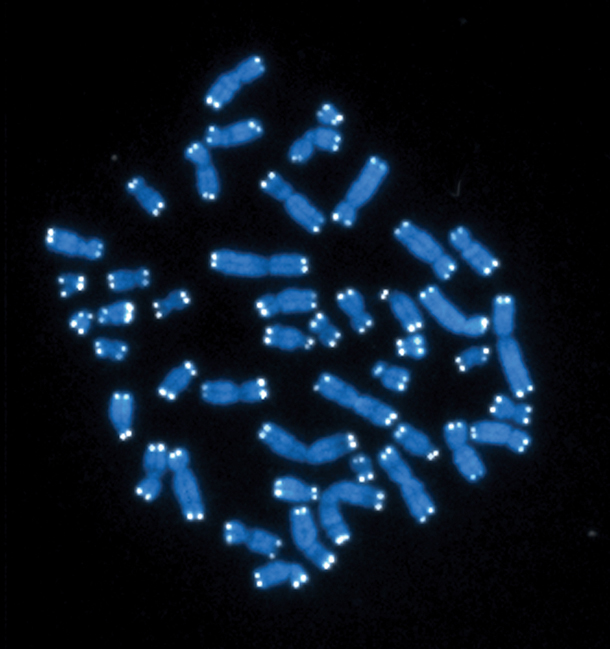

PERERA: Well, telomeres these repeated sequences of DNA that form a kind of cap on the ends of chromosomes, and they preserve the integrity of those chromosomes, and that's very important because it's been seen that, mostly in adults, that shorter telomeres are associated with cardiovascular illness, premature aging, cognitive decline and certain cancers. So, you want to have longer telomeres.

The human chromosomes are pictured in blue, while the white points at the ends of the chromosomes are telomeres. (Photo: NIH image gallery, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, longer life, longer telomeres.

PERERA: Yes, and that's why we use this particular biologic marker in this study in China because we could use it to see whether this was an additional benefit of the closure of a polluting coal plant.

CURWOOD: So, your study looked at blood from umbilical cords, pregnancies that – some occurred while the coal plant was operating, some occurred afterwards. What were the differences you found?

PERERA: There were many differences actually, and we, over the years, have been able to show that there were many benefits and this is just the latest one. The first thing we found was that the levels of this pollutant polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons – PAH for short – latched on to DNA were much lower in the second cohort. That's a good sign, less exposure. We also found that levels of a protein involved in early brain development called BDNF were much higher significantly so, and so here's the third short of chapter in this story where we looked at this novel biomarker called telomere, and asked the same question. Is there a difference? Do we see longer telomeres after the plant was shut down, meaning those babies did not have prenatal exposure to these particular combustion byproducts, and was the air pollution associated with shorter telomeres? And the answers to both of those questions were yes.

CURWOOD: Dr. Tang, so you found this difference. What does this difference mean for the outcome of the children?

TANG: At age two, we did another neural assessment. The difference between two cohorts is not statistically significant, but is showing there are some of the same trend. After the power plant was shut down, our air motoring data is showing significant reduction in terms of the air concentration of the PAHs. The reduce of the air pollution well improved the children's health in different ways in terms of the physical development also in the neural development too. A lot of those neural development issues, it's not reversible.

Frederica Perera is professor of Environmental Health Sciences and the Director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. (Photo: Columbia University)

CURWOOD: Dr. Tang, is there any way to quantify the value of shutting down this coal plant in terms of what it does to enhance human health?

TANG: We didn't quantify the health costs and another similar studies in China, we published two years earlier that we do a quantify the reduction of the pollution, what is the economic impact on the municipality in terms of the health costs which is very very significant. There is a perception saying that, oh, reduce environmental pollution may have a negative impact on the local economics. And actually, our evidence focused on the health costs alone, showing there is a tremendous improvement in terms of economic situation.

PERERA: I would add, may I add one thought, that in that analysis we didn't really talk much about the benefits to children from reducing pollution and that's something we're going to do more and more now based on results in this study and others we think that we can document the full spectrum of benefits, including to children's health and their long term health and functioning over their whole lifetimes and monetize those along with the conventional adult diseases and costs avoided there.

CURWOOD: It sounds like what you're saying that move out the coal plants and you have a smarter population?

PERERA: It looks that way. Less fossil fuel burning, cleaner air, smarter babies, healthier babies, healthier children and better life course health. So, yes I think there's good news. I should mention that this is the first study of telomeres in newborns. There have been studies in workers with exposures to specific chemicals, pesticides and a few very few studies in children but this is the first look into that very early window in cord blood when babies are first born.

CURWOOD: Dr. Tang, how has the government of China responded to your research?

TANG: We are very proud to be one of the very few environmental studies in China. The four environmental study teams operating in China are successful, and our study designs a way to document the effectiveness of the government policy and it brings the good news to the society. And also at this moment, China you know, facing a big challenge nationwide dealing with environmental health issues, and they are citing study cases as proof, and it's a hope to many other cities in China. As long as we're committed, the pollution can be reduced and the population health can be improved.

Deliang Tang is an associate professor of Environmental Health Sciences at the Mailman School of Public Health. (Photo: Columbia University)

CURWOOD: Dr. Perera, how has the United States government ... I'm thinking particularly the EPA, how have they responded to your research?

PERERA: Well, we haven't heard anything about this particular article, but in the past the government both at the federal level, as well as state and local levels have been very receptive to this information, and we've had a letter from Mayor Bloomberg in the past thanking us for our data that prompted more congestion relief in the city and other policies to reduce air pollution. We've testified before Congress and before legislators at the state level so there's been great receptivity. And I would hope that they'll be more of that in the future, so that science can actually inform and improve policymaking.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you for this research. I mean, intuitively you would think one would be healthier for not breathing air that's belched out of a smokestack of a coal fire power plant, but scientific evidence is important in these discussions.

PERERA: Absolutely, and no city in the world is free of these particular pollutants. Coal is obviously a big source in certain countries, but oil burning, even burning of natural gas, any kind of fossil fuel burning does release these pollutants along with fine particles and metals, a whole bunch of other toxic pollutants, and CO2 which is a main driver of climate change.

So, when you take all this evidence together including the telomeres, the implication here is that children are going to experience reduced risk of disease including premature aging. It's a good news story. It's a bit different from what we've done up to now, which is usually to tell the bad news to document these associations between pollution and adverse health effects in the children later on. So, here we had a nice opportunity to show good news and benefits of an intervention that the government did when they shut this plant down.

CURWOOD: Dr. Frederica Perera and Deliang Tang are professors at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Thank you for taking the time with me today.

TANG: Thank you, Steve.

PERERA: Thank you very much Steve. Pleasure.

Links

The study on telomere length and air pollution, published in the journal Environmental International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth