Free the Beaches: Desegregating America’s Shoreline

Air Date: Week of May 25, 2018

The US civil rights movement to end racial segregation in the 1960’s may have been most intense the South, but there were battles in the North, including in the State of Connecticut. Just about all of the Long Island Sound beaches in Connecticut were off limits to people of color until Ned Coll came along. In his 2018 book Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline, historian Andrew Kahrl describes Coll’s creative protests to smash the color bar and let all children cool off on hot days at the beach. He spoke with host Steve Curwood.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Back in 1959 a physician in Biloxi Mississippi led a group of black people onto a segregated beach to protest discrimination. The protestors were repulsed by white homeowners and the police, but the “wade in” – as it was dubbed, became part of the civil rights movement not only in the deep South but also in the North.

Connecticut and other northern states also had a long history of wealthy white folks barring people of color and the less affluent from their sandy shorelines. So in the 1960s the Connecticut beaches on Long Island Sound became the target of wade-ins, often led by activist Ned Coll. Historian Andrew Kahrl has written a book titled, Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline. Andrew, welcome to Living on Earth!

KAHRL: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Please describe for us briefly what the beaches were like along the Connecticut shore in the 60s and 70s, and who got to use them?

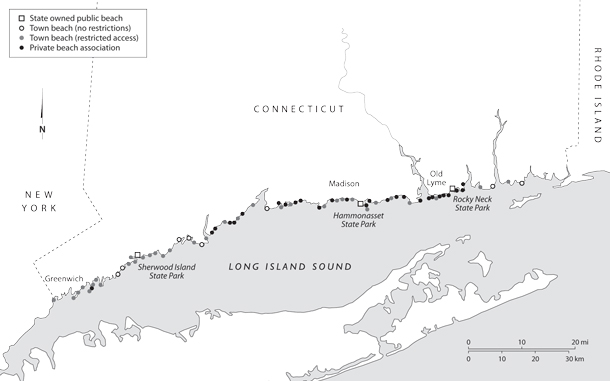

KAHRL: Well, they were very limited in their public access. It was a 253-mile shoreline, 72 miles of it was white sand beaches, and of that only seven miles were open to the public. The rest were in the hands of private homeowners, private beach associations, which were sort of like gated communities, as well as clubs and other residential corporations. So, it was, it was a shoreline that has, was effectively off limits to the general public. It was something that really was exclusive to the upper-middle class and wealthy communities that were fortunate enough to live or own summer cottages along the shore.

CURWOOD: So, on to this scene of unequal beach access comes Ned Coll. Who was he and what led him to lead a campaign to free the beaches?

KAHRL: Yeah, so Ned Coll was a young white Irish Catholic, recent college grad, who in 1964, he was working in a comfortable job in the insurance industry in Hartford, Connecticut, and had. You know, was very distraught after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, sensed that spirit of a kind of new frontier of volunteerism of civic engagement was in danger after his death, and quit his job and decided to found an anti-poverty organization called Revitalization Corps. It was – he fashioned it as a domestic Peace Corps that aim to get middle-class, white Americans, primarily those who sort of were living in sort of relative privilege and comfort to become more involved in solving the problems of poverty, of segregation and of racism in America.

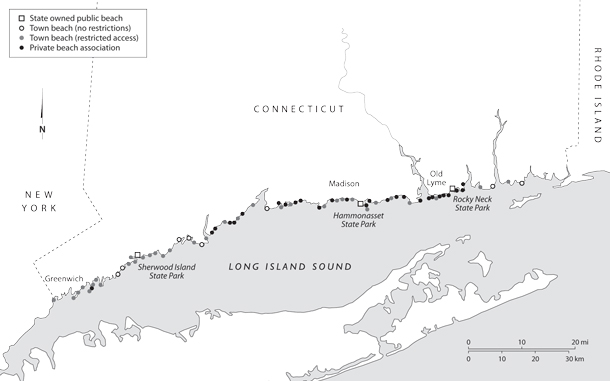

Names, locations, and legal status of public beaches along Connecticut’s Gold Coast. (Image: Andrew Kahrl)

He came to the issue of beach access almost by accident. He and the volunteers, many African-American mothers who lived in the communities where he was serving wanted to sort of find ways to get children out of the city during the summer, give them more cultural enrichment activities, whether it be trips to the countryside or other excursions, and they just decided during the summer of 1971 that they would start leading trips down to the shore. They didn't think of it as a protest at all. They thought of it as just another sort of activity that they could do during the summer when kids are out of school. They loaded up a bus of children and mothers and headed down to the state shoreline and discovered that there was very little access available to them. There was few places that they could actually go, and the beaches that they did try to access, they were not welcomed at.

CURWOOD: Hey, remind us how much access that poor black kids growing up in public housing in the 60s and 70s had to places where they could play or cool off on hot summer days there in Connecticut, whether it's Bridgeport or Hartford or whatever.

KAHRL: No, this was a real serious issue. I mean, this was something I talked a lot about in the book is how the summer season really brought a whole host of injustices and deprivations into focus, and it was oftentimes as a result of tragedy. There was a shockingly high number of children in cities like Hartford and Harlem in many cities across the country that would would drown each summer oftentimes playing in unsupervised bodies of water and they were there because there was few other options available. This was something that the Kerner Commission which studied civil disorder in the 1960s and looked to sort of understand the roots of African-American unrest found that, in fact, recreation and the sort of lack of decent and safe places of recreation ranked very high on the list of African-American grievances in some of the cities or racked by violence during these years.

CURWOOD: What did the law say about the public right to access the beaches and where did the idea that beaches belong to everyone come from originally?

KAHRL: Yeah, I mean the idea that the shoreline belonged to the public originated in the Roman Empire. In the year 530 C.E. the Roman emperor Justinian proclaimed that shorelines are common to mankind, that they’re subject to the same law as the sea itself and that no law one can be forbidden from approaching them.

This idea what's later became known as the public trust doctrine has deep deep roots in western law. It formed the basis of the English common law, this notion that beaches were public land and then it became part of American common law with the founding of the Republic. So, this notion that beaches are public property has deep deep roots in American law.

CURWOOD: So, Ned Coll begins really a campaign to free the beaches and he takes this busload of kids and mothers down to the shore and there's not a lot of access. What's the turning point when he decides, hey, I need to make this a cause?

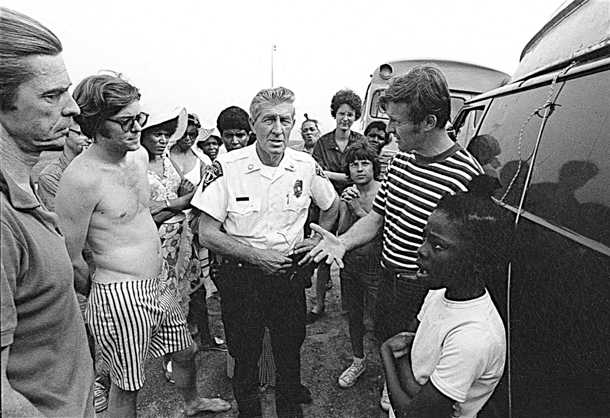

KAHRL: Yeah, really I think you can sort of date it back to that summer of 1971 when they went to the town of Old Lyme, Connecticut, which was one of the many old, upper middle class wealthier communities along the shore, and were greeted very hostilely by the homeowners who felt as if, this was their private beach, this was, they were trying to sort of access what was a private beach association's shoreline. The sort of anger and hostility that greeted him really unnerved him and woke him up to some of the realities of racism in these places that had not really been on their radar. I mean, these are isolated small, sort of little summer enclaves of people of sort of great privilege and it turned his attention to seeking to first engage with these communities and as they became increasingly resistant and hostile to his very presence, seeking to sort of protest and draw attention to this issue.

CURWOOD: There's a passage from your book that describes one of his demos, if you could call that. It's an amphibious invasion of one of these beaches. Could you please read from your book there? I think it's page 187.

KAHRL: Yeah, sure.

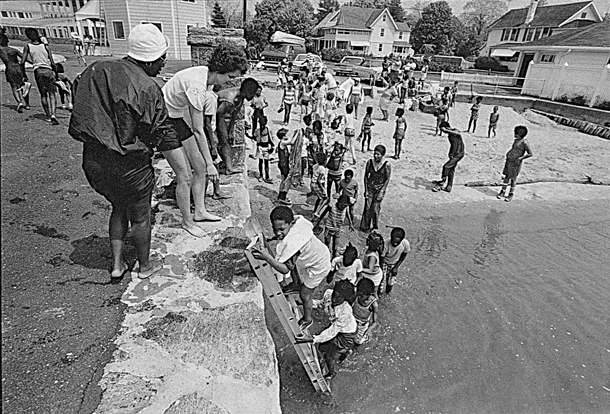

On the ride to the shore the kids could barely contain their excitement it would be a Fourth of July to remember. As the Long Island Sound came into view, the vans pulled into the boat landing located next to the private club whose festivities they would soon be crashing. Ned and one of his assistants leapt out of the van and began unfastening the boats from the roof and dropping them into the water. Someone else hung a ladder off the pier.

Once everything was in place, Ned and the volunteers scurried down the ladder and into the boats. The children strapped on their life jackets, climbed aboard the vessels and headed out to sea. On the shore members of the exclusive Madison Beach Club who underwent a rigorous vetting process and paid a $300 annual membership for days like this were trickling out onto the beach and planting themselves underneath one of the club's neatly arranged green umbrellas. Just before noon, three boats appeared, all headed toward the club shore. Ned, with an American flag attached to a pole, leaped off the bow and began marching, MacArthuresque, toward the beach, stopping just before he reached the dry sand he shouted, "Happy Fourth of July everyone," and defiantly planted the flag in the sand.

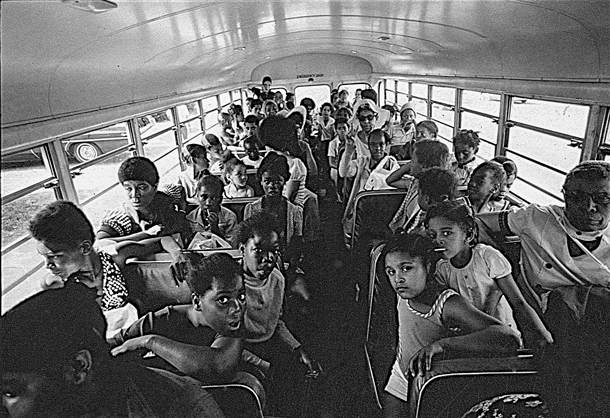

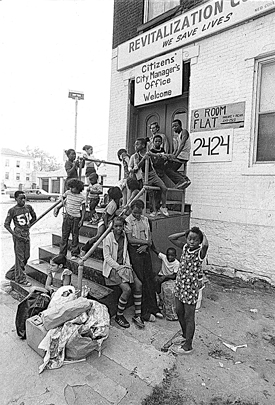

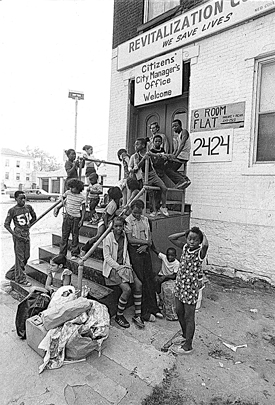

Children and staff outside Revitalization Corps’s headquarters on Hartford’s North End, c. 1975. (Photo: courtesy of Bob Adelman)

Moments later a plane began circling overhead carrying a banner that read, "Free America's beaches". Club members stared in disbelief. This was an ambush. Parents sqooped their children off the beach and made a hasty retreat to the clubhouse.

CURWOOD: Sounds like those folks were scared.

KAHRL: Yeah, in a sense, it was kind of unlike anything they had ever seen before because the shoreline in many of these towns had been so effective in the limited public access, and not just limiting public access to the beach, but also sort of limiting diversity within their communities. I mean, one of the things that I talk a lot about in the book is the way that many of these towns had and acted exclusionary zoning ordinances that prevented low-income housing or really sort of preventing anyone below a certain income level from being able to live in these towns. So, these were virtually all white and very sort of class homogenous as well. So, the very presence of a busload of children from inner city Hartford was unthinkable for them.

The one thing that I think that really sort of stood out to me especially as someone who had who had previously studied desegregation of shorelines in the South during the civil rights movement at a time where there was horrific violence characterized by efforts to desegregate beaches, you know, wade-ins that took place where mobs of white segregationists would come out into the water with baseball bats and tire irons and violence would sort of erupt. Here in these sort of very well-to-do communities, oftentimes the response was to simply sort of retreat to the clubhouse, remove their children. That was really one of the saddest things is that white and black children would be playing together here on the shore and parents would grab their children and sort of take them away as if that this was some sort of threat to them. At first they sort of reacted with a degree of shock and then anger and hostility as they realized that Ned wasn't coming there seeking permission. They were coming there as asserting their right to access this beach whenever they pleased.

CURWOOD: Now, after a while, of course, there’s litigation, and the advocates for freeing the beaches move ahead, in many cases in court. What stands out as most significant among those cases?

KAHRL: The protests that Ned Coll and others were waging in Connecticut dovetailed with this open beaches movement, which was really national in scope, and from one 1970 to 1980, there were over 150 beach access cases heard in state and local courts. That's up from 10 the previous decade. One of the issues that many of these cases challenged was the right of local communities that had accepted substantial amounts of state and federal tax dollars to help build and enhance their shorelines. Whether they could limit access to residents only when it was really everyone who had helped to pay for these facilities. Now, the interesting thing that happened in Connecticut was the way that very wealthy towns like Greenwich and Madison interpreted these cases was to say, well, the solution for us is to never accept state or federal tax dollars, and they were wealthy enough that they could do that. And so Greenwich in particular developed almost a phobia of any outside funding that was being dangled before them fearing as if it would be some sort of poison chalice that would then lead them into court.

CURWOOD: You write that when some of these communities who were forced to open up their shorelines "to the public" that they found some rather ingenious ways to – and I say that in the diabolical sense of the word –

KAHRL: Mmhmm.

CURWOOD: to nonetheless keep people out. Can you give me some examples?

KAHRL: Yes, so in 2001, the state of Connecticut, the state Supreme Court declared that the restrictions that Greenwich and many others communities were using that explicitly barred nonresidents from accessing their shorelines was unconstitutional. So, at that point legally the beaches were open to everyone, but towns were finding new ways to sort of get around this, and so it could either be through very limited parking access or say having parking lots that only residents could park in. Selling beach passes in a way that was – made it very difficult for non-residents to actually purchase them, but oftentimes, on this issue in particular, there was a real effort to distance ... these communities really stressed that their beach access policies had nothing to do with race. It was simply a matter of private property rights, of the rights of local communities to limit access to residents only, and even went so far oftentimes in a very cynical way to acclaim that they were restricting access out of environmental concerns, that they were fearing that if they letting anyone on to the shores then the shores themselves would be harmed.

CURWOOD: So, basically nature designed the beaches, the coastal areas to be dynamic. That at times the coastline would receded, at other times it would advance. What has all this privatization of beaches done for our ecology do you think, and the lesson we might be able to learn?

KAHRL: Yeah, you're absolutely right. I mean, beaches exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium. They're in constant motion. They resist any attempt to sort of stabilize and yet that is sort of the story of coastal America in the 20th century was this constant effort to try to sort of hold beaches in place, whether it be through sea walls, beach nourishment projects. I mean, we spent millions of dollars a year pumping sand onto shorelines in the interest of sort of making them attractive to vacationers or to homeowners and yet much of this is not only sort of is oftentimes quite literally washed out to sea when a storm hits but as well makes the sort of problems that sea level rise poses all the more daunting and pushes us further away from a more sensible and more sustainable relationship with these very fragile stretches of land.

Andrew Kahrl is an associate professor of history and African American studies at the University of Virginia. (Photo: University of Virginia)

And one of the problems that I see ... this was plainly evident after Superstorm Sandy in 2012 was a reluctance to face up to the reality and to heed the call that many coastal scientists have been issuing for years now, which is that we need to begin to retreat from areas that are highly vulnerable to sea level rise and will be uninhabitable, and yet we consistently resist that and instead double down on development and double down on rebuilding. And what drives this? Well, in part it's that ability to be able to sort of colonize the shore and claim beachfront property as your own. This is highly desirable real estate and it's made all the more desirable by the ability of homeowners to be able to not just sort of enjoy the spaces but also to restrict access to others.

CURWOOD: You're an academic, you're not a judge or jury, but how would you rate Ned Coll’s success in his enterprise to try to desegregate Connecticut's beaches?

KAHRL: Well, I think it's undeniable that the activism that he engaged in in the 1970s raised awareness of not just the issue of beach access, but of a larger set of inequalities that were shaping life in the northeast and across the country. For a time Revitalization Corps was really truly national in scope. It spawned hundreds of volunteers, dozens of chapters across the country. People really were drawn to his spirit of civic engagement and sort of local activism, but ultimately it struggled to make long-term gains because of Ned's reluctance to sort of work with others, and to sort of partner with other organizations and to really put in place an infrastructure that would allow communities to organize themselves, and because he was so single-minded in his focus and so adamant in his beliefs, and the issues he cared deeply about that it was oftentimes sort of his way or the highway.

Now that said, the gains that have been made with regard to public beach access are significant. I think that the decision in 2001 by the Connecticut Supreme Court that opened up the state's shoreline to the public could not have been possible were it not for the activism of Ned Coll in the 1970s. But we still see across America this steady trend toward closing off public access and of increased sort of retreat amongst many Americans into private spaces, and that really poses a threat to our democracy as a whole. I mean, as I argue in the book, public space plays a very essential role in a democratic society. These are sort of places where people of different backgrounds, races and ethnicities and income levels can come into contact with each other and really in the process learn how to get along and when we don't have that it leads toward increased polarization, increased division, increased parochialism, and I think the cause that he was championing is an important one that still remains very much with us today.

CURWOOD: Andrew Kahrl teaches history and African-American studies at the University of Virginia. His book is called "Free the Beaches." Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KAHRL: Thank you for having me.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

The US civil rights movement to end racial segregation in the 1960’s may have been most intense the South, but there were battles in the North, including in the State of Connecticut. Just about all of the Long Island Sound beaches in Connecticut were off limits to people of color until Ned Coll came along. In his 2018 book Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline, historian Andrew Kahrl describes Coll’s creative protests to smash the color bar and let all children cool off on hot days at the beach. He spoke with host Steve Curwood.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Back in 1959 a physician in Biloxi Mississippi led a group of black people onto a segregated beach to protest discrimination. The protestors were repulsed by white homeowners and the police, but the “wade in” – as it was dubbed, became part of the civil rights movement not only in the deep South but also in the North.

Connecticut and other northern states also had a long history of wealthy white folks barring people of color and the less affluent from their sandy shorelines. So in the 1960s the Connecticut beaches on Long Island Sound became the target of wade-ins, often led by activist Ned Coll. Historian Andrew Kahrl has written a book titled, Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline. Andrew, welcome to Living on Earth!

KAHRL: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Please describe for us briefly what the beaches were like along the Connecticut shore in the 60s and 70s, and who got to use them?

KAHRL: Well, they were very limited in their public access. It was a 253-mile shoreline, 72 miles of it was white sand beaches, and of that only seven miles were open to the public. The rest were in the hands of private homeowners, private beach associations, which were sort of like gated communities, as well as clubs and other residential corporations. So, it was, it was a shoreline that has, was effectively off limits to the general public. It was something that really was exclusive to the upper-middle class and wealthy communities that were fortunate enough to live or own summer cottages along the shore.

CURWOOD: So, on to this scene of unequal beach access comes Ned Coll. Who was he and what led him to lead a campaign to free the beaches?

KAHRL: Yeah, so Ned Coll was a young white Irish Catholic, recent college grad, who in 1964, he was working in a comfortable job in the insurance industry in Hartford, Connecticut, and had. You know, was very distraught after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, sensed that spirit of a kind of new frontier of volunteerism of civic engagement was in danger after his death, and quit his job and decided to found an anti-poverty organization called Revitalization Corps. It was – he fashioned it as a domestic Peace Corps that aim to get middle-class, white Americans, primarily those who sort of were living in sort of relative privilege and comfort to become more involved in solving the problems of poverty, of segregation and of racism in America.

Names, locations, and legal status of public beaches along Connecticut’s Gold Coast. (Image: Andrew Kahrl)

He came to the issue of beach access almost by accident. He and the volunteers, many African-American mothers who lived in the communities where he was serving wanted to sort of find ways to get children out of the city during the summer, give them more cultural enrichment activities, whether it be trips to the countryside or other excursions, and they just decided during the summer of 1971 that they would start leading trips down to the shore. They didn't think of it as a protest at all. They thought of it as just another sort of activity that they could do during the summer when kids are out of school. They loaded up a bus of children and mothers and headed down to the state shoreline and discovered that there was very little access available to them. There was few places that they could actually go, and the beaches that they did try to access, they were not welcomed at.

CURWOOD: Hey, remind us how much access that poor black kids growing up in public housing in the 60s and 70s had to places where they could play or cool off on hot summer days there in Connecticut, whether it's Bridgeport or Hartford or whatever.

KAHRL: No, this was a real serious issue. I mean, this was something I talked a lot about in the book is how the summer season really brought a whole host of injustices and deprivations into focus, and it was oftentimes as a result of tragedy. There was a shockingly high number of children in cities like Hartford and Harlem in many cities across the country that would would drown each summer oftentimes playing in unsupervised bodies of water and they were there because there was few other options available. This was something that the Kerner Commission which studied civil disorder in the 1960s and looked to sort of understand the roots of African-American unrest found that, in fact, recreation and the sort of lack of decent and safe places of recreation ranked very high on the list of African-American grievances in some of the cities or racked by violence during these years.

CURWOOD: What did the law say about the public right to access the beaches and where did the idea that beaches belong to everyone come from originally?

KAHRL: Yeah, I mean the idea that the shoreline belonged to the public originated in the Roman Empire. In the year 530 C.E. the Roman emperor Justinian proclaimed that shorelines are common to mankind, that they’re subject to the same law as the sea itself and that no law one can be forbidden from approaching them.

This idea what's later became known as the public trust doctrine has deep deep roots in western law. It formed the basis of the English common law, this notion that beaches were public land and then it became part of American common law with the founding of the Republic. So, this notion that beaches are public property has deep deep roots in American law.

CURWOOD: So, Ned Coll begins really a campaign to free the beaches and he takes this busload of kids and mothers down to the shore and there's not a lot of access. What's the turning point when he decides, hey, I need to make this a cause?

KAHRL: Yeah, really I think you can sort of date it back to that summer of 1971 when they went to the town of Old Lyme, Connecticut, which was one of the many old, upper middle class wealthier communities along the shore, and were greeted very hostilely by the homeowners who felt as if, this was their private beach, this was, they were trying to sort of access what was a private beach association's shoreline. The sort of anger and hostility that greeted him really unnerved him and woke him up to some of the realities of racism in these places that had not really been on their radar. I mean, these are isolated small, sort of little summer enclaves of people of sort of great privilege and it turned his attention to seeking to first engage with these communities and as they became increasingly resistant and hostile to his very presence, seeking to sort of protest and draw attention to this issue.

CURWOOD: There's a passage from your book that describes one of his demos, if you could call that. It's an amphibious invasion of one of these beaches. Could you please read from your book there? I think it's page 187.

KAHRL: Yeah, sure.

On the ride to the shore the kids could barely contain their excitement it would be a Fourth of July to remember. As the Long Island Sound came into view, the vans pulled into the boat landing located next to the private club whose festivities they would soon be crashing. Ned and one of his assistants leapt out of the van and began unfastening the boats from the roof and dropping them into the water. Someone else hung a ladder off the pier.

Once everything was in place, Ned and the volunteers scurried down the ladder and into the boats. The children strapped on their life jackets, climbed aboard the vessels and headed out to sea. On the shore members of the exclusive Madison Beach Club who underwent a rigorous vetting process and paid a $300 annual membership for days like this were trickling out onto the beach and planting themselves underneath one of the club's neatly arranged green umbrellas. Just before noon, three boats appeared, all headed toward the club shore. Ned, with an American flag attached to a pole, leaped off the bow and began marching, MacArthuresque, toward the beach, stopping just before he reached the dry sand he shouted, "Happy Fourth of July everyone," and defiantly planted the flag in the sand.

Children and staff outside Revitalization Corps’s headquarters on Hartford’s North End, c. 1975. (Photo: courtesy of Bob Adelman)

Moments later a plane began circling overhead carrying a banner that read, "Free America's beaches". Club members stared in disbelief. This was an ambush. Parents sqooped their children off the beach and made a hasty retreat to the clubhouse.

CURWOOD: Sounds like those folks were scared.

KAHRL: Yeah, in a sense, it was kind of unlike anything they had ever seen before because the shoreline in many of these towns had been so effective in the limited public access, and not just limiting public access to the beach, but also sort of limiting diversity within their communities. I mean, one of the things that I talk a lot about in the book is the way that many of these towns had and acted exclusionary zoning ordinances that prevented low-income housing or really sort of preventing anyone below a certain income level from being able to live in these towns. So, these were virtually all white and very sort of class homogenous as well. So, the very presence of a busload of children from inner city Hartford was unthinkable for them.

The one thing that I think that really sort of stood out to me especially as someone who had who had previously studied desegregation of shorelines in the South during the civil rights movement at a time where there was horrific violence characterized by efforts to desegregate beaches, you know, wade-ins that took place where mobs of white segregationists would come out into the water with baseball bats and tire irons and violence would sort of erupt. Here in these sort of very well-to-do communities, oftentimes the response was to simply sort of retreat to the clubhouse, remove their children. That was really one of the saddest things is that white and black children would be playing together here on the shore and parents would grab their children and sort of take them away as if that this was some sort of threat to them. At first they sort of reacted with a degree of shock and then anger and hostility as they realized that Ned wasn't coming there seeking permission. They were coming there as asserting their right to access this beach whenever they pleased.

CURWOOD: Now, after a while, of course, there’s litigation, and the advocates for freeing the beaches move ahead, in many cases in court. What stands out as most significant among those cases?

KAHRL: The protests that Ned Coll and others were waging in Connecticut dovetailed with this open beaches movement, which was really national in scope, and from one 1970 to 1980, there were over 150 beach access cases heard in state and local courts. That's up from 10 the previous decade. One of the issues that many of these cases challenged was the right of local communities that had accepted substantial amounts of state and federal tax dollars to help build and enhance their shorelines. Whether they could limit access to residents only when it was really everyone who had helped to pay for these facilities. Now, the interesting thing that happened in Connecticut was the way that very wealthy towns like Greenwich and Madison interpreted these cases was to say, well, the solution for us is to never accept state or federal tax dollars, and they were wealthy enough that they could do that. And so Greenwich in particular developed almost a phobia of any outside funding that was being dangled before them fearing as if it would be some sort of poison chalice that would then lead them into court.

CURWOOD: You write that when some of these communities who were forced to open up their shorelines "to the public" that they found some rather ingenious ways to – and I say that in the diabolical sense of the word –

KAHRL: Mmhmm.

CURWOOD: to nonetheless keep people out. Can you give me some examples?

KAHRL: Yes, so in 2001, the state of Connecticut, the state Supreme Court declared that the restrictions that Greenwich and many others communities were using that explicitly barred nonresidents from accessing their shorelines was unconstitutional. So, at that point legally the beaches were open to everyone, but towns were finding new ways to sort of get around this, and so it could either be through very limited parking access or say having parking lots that only residents could park in. Selling beach passes in a way that was – made it very difficult for non-residents to actually purchase them, but oftentimes, on this issue in particular, there was a real effort to distance ... these communities really stressed that their beach access policies had nothing to do with race. It was simply a matter of private property rights, of the rights of local communities to limit access to residents only, and even went so far oftentimes in a very cynical way to acclaim that they were restricting access out of environmental concerns, that they were fearing that if they letting anyone on to the shores then the shores themselves would be harmed.

CURWOOD: So, basically nature designed the beaches, the coastal areas to be dynamic. That at times the coastline would receded, at other times it would advance. What has all this privatization of beaches done for our ecology do you think, and the lesson we might be able to learn?

KAHRL: Yeah, you're absolutely right. I mean, beaches exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium. They're in constant motion. They resist any attempt to sort of stabilize and yet that is sort of the story of coastal America in the 20th century was this constant effort to try to sort of hold beaches in place, whether it be through sea walls, beach nourishment projects. I mean, we spent millions of dollars a year pumping sand onto shorelines in the interest of sort of making them attractive to vacationers or to homeowners and yet much of this is not only sort of is oftentimes quite literally washed out to sea when a storm hits but as well makes the sort of problems that sea level rise poses all the more daunting and pushes us further away from a more sensible and more sustainable relationship with these very fragile stretches of land.

Andrew Kahrl is an associate professor of history and African American studies at the University of Virginia. (Photo: University of Virginia)

And one of the problems that I see ... this was plainly evident after Superstorm Sandy in 2012 was a reluctance to face up to the reality and to heed the call that many coastal scientists have been issuing for years now, which is that we need to begin to retreat from areas that are highly vulnerable to sea level rise and will be uninhabitable, and yet we consistently resist that and instead double down on development and double down on rebuilding. And what drives this? Well, in part it's that ability to be able to sort of colonize the shore and claim beachfront property as your own. This is highly desirable real estate and it's made all the more desirable by the ability of homeowners to be able to not just sort of enjoy the spaces but also to restrict access to others.

CURWOOD: You're an academic, you're not a judge or jury, but how would you rate Ned Coll’s success in his enterprise to try to desegregate Connecticut's beaches?

KAHRL: Well, I think it's undeniable that the activism that he engaged in in the 1970s raised awareness of not just the issue of beach access, but of a larger set of inequalities that were shaping life in the northeast and across the country. For a time Revitalization Corps was really truly national in scope. It spawned hundreds of volunteers, dozens of chapters across the country. People really were drawn to his spirit of civic engagement and sort of local activism, but ultimately it struggled to make long-term gains because of Ned's reluctance to sort of work with others, and to sort of partner with other organizations and to really put in place an infrastructure that would allow communities to organize themselves, and because he was so single-minded in his focus and so adamant in his beliefs, and the issues he cared deeply about that it was oftentimes sort of his way or the highway.

Now that said, the gains that have been made with regard to public beach access are significant. I think that the decision in 2001 by the Connecticut Supreme Court that opened up the state's shoreline to the public could not have been possible were it not for the activism of Ned Coll in the 1970s. But we still see across America this steady trend toward closing off public access and of increased sort of retreat amongst many Americans into private spaces, and that really poses a threat to our democracy as a whole. I mean, as I argue in the book, public space plays a very essential role in a democratic society. These are sort of places where people of different backgrounds, races and ethnicities and income levels can come into contact with each other and really in the process learn how to get along and when we don't have that it leads toward increased polarization, increased division, increased parochialism, and I think the cause that he was championing is an important one that still remains very much with us today.

CURWOOD: Andrew Kahrl teaches history and African-American studies at the University of Virginia. His book is called "Free the Beaches." Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KAHRL: Thank you for having me.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth