An American Eden: The Lost Garden Underneath Rockefeller Center

Air Date: Week of July 6, 2018

The generation that followed the “founding fathers” had big shoes to fill. So they founded civic institutions like museums, universities, and its first botanical garden to earn the fledgling republic world respect. Historian Victoria Johnson, author of "American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic," spoke with Host Jenni Doering about the foresighted physician who founded the Elgin Botanic Garden in what’s now Rockefeller Center to advance the study of medicinal plants.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In 1776, fifty-six patriots signed their names to a bold document that planted the seed of a new nation, and men like Franklin, Adams, and Jefferson became the “founding fathers.” Less famous is the generation that followed. The Americans who grew up just as the Revolution unfolded saw that the young, fragile democratic experiment would need civic institutions: museums, universities, and even botanical gardens. The Elgin Botanic Garden was once in the heart of what’s now Midtown Manhattan. It was the life’s work of a well-known doctor and medical botanist, David Hosack. Historian Victoria Johnson has written “American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic.” Victoria, welcome to Living on Earth.

JOHNSON: Thank you. I'm so happy to be with you.

DOERING: So, David Hosack isn't a household name, but it's also clear from your book that he helped shape America in the republic's early years. So, who was he?

JOHNSON: David Hosack was the most famous man most of us have never heard of. If he's known at all, it's for having been the attending physician at the duel with Hamilton and Burr. He was chosen by both men. But that was only one of many, many things he became famous for, including founding the first botanical garden in the new nation. He was the reason that New York became New York in his generation, the premier city for the arts and sciences. He was a founder or co-founder of the New-York Historical Society, Bellevue Hospital, the city's first obstetrics hospital, its first mental hospital, its first public schools, its first school for the deaf, its first subsidized pharmacy for the poor, and on and on and on.

American Eden is Victoria Johnson’s third book. (Image: courtesy of W.W. Norton)

Hosack was a teenager walking through New York City, passing people like Hamilton and Burr and George Washington and Thomas Jefferson on the street in New York City. He grew up as a very young child under the British occupation of Manhattan. He saw heroism and sacrifice all around him, and what does that next generation do that's heroic? If your elders have brought an entire nation into being, what do you do as a teenager, what do you aspire to? If you're David Hosack and many of his peers, you want to make the nation great, you want to build the civic institutions that will make it stable, that will bring it world respect, that will help fellow citizens live happy, healthy lives.

DOERING: How did you come across his story, and what inspired you to write this book?

JOHNSON: I love the natural environment, and as a professor who specializes in the history of organizations, I was fascinated to read a description of a couple of pages of David Hosack and his lost garden at the heart of Manhattan. I read it in a wonderful book about the founding of the much later New York Botanical Garden – that was founded 90 years later in the late 19th century – and that story grabbed me from that first second, and the more I learned about him, the more I realized that he was truly a great forgotten American.

DOERING: And in the midst of all that research, we have the musical “Hamilton” which just exploded. And he had this connection with Hamilton. Can you talk a little bit about that?

JOHNSON: Yes, in 1797, so seven years before the duel, Hosack had been called in to a dire situation facing the Hamilton family. Hamilton's son Philip was stricken with a terrible fever, and Hosack saved Philip Hamilton's life by doing some unusual risky things for the time which involved drawing a steaming bath and sprinkling in Peruvian bark, a botanical remedy. Normally, the choice would have been bloodletting or mercury or cold cloths to try to lower the fever. And when Hosack had gotten Philip out of danger, he retired to a bedroom in the house. He wanted to stay in the Hamilton house to make sure that Philip was all right. And he fell asleep, and he woke up suddenly to find Alexander Hamilton at his bedside, kneeling, with tears in his eyes. He took his hand and thanked him for saving the life of his very precious eldest son Philip. And that episode earned Hosack Hamilton's trust and gratitude, and Hosack became Hamilton's family physician.

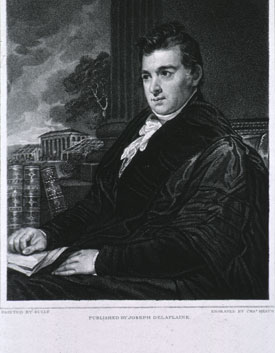

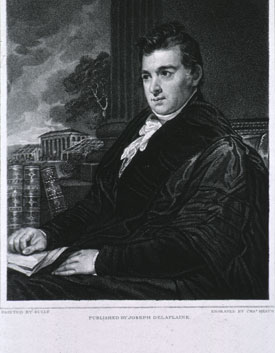

David Hosack with his botanical garden in the distance (now Rockefeller Center), by Charles Heath, engraving, 1816. Collections of the National Library of Medicine.

DOERING: Hosack seemed to have this faith in botanicals and plants to help with medical remedies. How revolutionary was that? And where did he get that from?

JOHNSON: There was some attention to botanical remedies among doctors with whom Hosack studied, when he studied in New York and in Philadelphia as a very young man. But they were mostly thought of as supplies to be bought at apothecary shops. A lot of the medications were imported, such as Peruvian bark, the most powerful of the contemporary medicines. And they were also used in conjunction with much more radical and sometimes deathly treatments like mercury, which is toxic. And American medicine was still far enough behind European medicine that many of his doctors had trained in Great Britain. So, he decided to sail to Edinburgh himself. It was there that he discovered his life's other great passion – botany. He discovered that Europe was blanketed in botanical gardens, and that for European doctors and medical professors, botanical gardens were laboratories, classrooms, and encyclopedias, all rolled into one. That was where you trained students in medical botany. But what Hosack learned, in addition to falling in love with botany, he learned that no one really knew how to isolate, how to identify new plant-based medicines. And when he returned to the United States two years later, after a full year of daily medical botany training, he was obsessed with the idea that the North American continent was blanketed in undiscovered medicinal plants.

DOERING: So, he comes back to the United States and begins practicing medicine. What does he do next?

JOHNSON: Hosack was appointed a professor of botany and medicine at Columbia [University] shortly after he returned, and he taught his students as best he could out of books, taught them medical botany. He told his students that a doctor must know his foods and medicines from his poisons, but he felt incredibly frustrated that he couldn't teach his students using actual plants. So, he lobbied Columbia for funds to launch a botanical garden, and they said yes, but they were pretty cash-strapped. Finally, he just bought 20 acres of land with his own money. He went three-and-a-half miles north of New York City to buy this land to rural Manhattan, and he would ride up this country lane called the Middle Road into rolling hills, farms. The woodlands of Manhattan had largely been cut down, but there were still groves, and he could see both rivers and mountain laurel and wild grasses and wild flowers. It was completely pastoral, and he decided that if he launched the garden by himself, his fellow citizens would eventually come to their senses and make it truly a public garden.

DOERING: So, I'm wondering what came of his vision to create this botanical garden where physicians could study the medical properties of plants. How useful did it become?

JOHNSON: The garden – it brought Hosack great renown. And Hosack accomplished several things with the Elgin Botanic Garden. He trained an entire generation of doctors not only in how to care for their patients and the medical uses of particular plants, but he also taught them the scientific method.

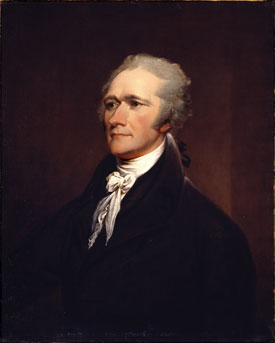

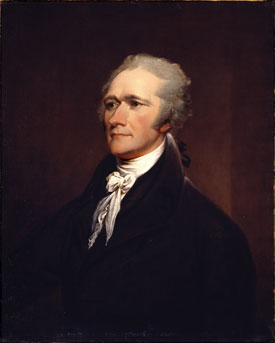

The portrait Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull, oil on canvas, 1806. David Hosack was Hamilton’s friend and physician, and tended to him after the fatal duel with Aaron Burr. (Photo: Collections of the National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

He trained them in such a way that when medicine moved on after his death more towards the chemistry laboratory and away from botany, he had equipped a whole generation of medical researchers in how to pursue their questions and find answers. He also brought in to being a generation of a professional American botanists where there had been pretty much none before. Most people studying botany in the early republic were gentleman polymaths or they were sort of collectors collecting for nurseries for commercial purposes. And it was Hosack's students and their students who went on to found botanical gardens across the country. The founders of the great New York Botanical Garden were students of Hosack's prized students – so, Hosack's intellectual grandchildren. So, the New York Botanical Garden was founded in the 1890s, and he is present everywhere you go in the garden today, the New York Botanical Garden. The devotion to collecting plants from all over the world, to understand ecosystems around the world, to education of New Yorkers and international visitors… He is everywhere there – his spirit and what he dreamed of – and I love walking around that glorious garden and thinking how happy Hosack would be if he could see it.

DOERING: It was so heartbreaking reading about the collapse of Elgin, this dream and this paradise, this American Eden that he had built in what was then the country of Manhattan, but what is now Rockefeller Center. Why did it happen? Why did it collapse? And what did that mean to him and to his fellow Americans who wanted this garden to be successful?

JOHNSON: He did have a moment of triumph where he managed to get public funding. He lobbied for an entire decade to get the state of New York to take it over and run it as a public institution. He was in debt constantly, but he kept pouring his own money into this institution because he believed in it so much. And he eventually spent more than a million in today's dollars on it out of his own pocket. So, he did have this pinnacle of success in around 1810. He was able to persuade the state of New York to pass an act purchasing the garden to run for the public benefit.

Hosackia stolonifera (Creeping-Rooted Hosackia), from Edward’s Botanical Register, vol. 23 (1837).

So, he actually triumphed. He got what he had always wanted, which was not to build a garden for his own glory but to build a garden for his fellow citizens. The aftermath of that is the garden was given to Columbia College to run for the public benefit. Hosack soon realized to his horror that Columbia wasn't committed to maintaining the garden, in part because of its incredible expense. The garden collapsed. They looked the other way while the caretaker took plants and sold them downtown in a shop, and the conservatory fell apart. The glass panes shattered on the floor, and his arboretum was ripped out and carried up the island to beautify a new insane asylum that was being built. So, he watched the garden fall apart, and this was incredibly painful to him. But he had a great sense of humor and he also had a great sense of drama. And after trying over and over to get the garden back from Columbia – to lease the land back and recreate the garden – he made a purchase which, I think, was his way of saying, I'm moving on. He purchased from a young friend one of the most famous paintings from American history, the “Expulsion from the Garden of Eden” by Thomas Cole. And Cole was a young painter at the time trying to sell this painting, and Hosack ran into Cole in the street shortly after he had finally given up on getting the garden back, and he made Cole an offer on the spot. And Hosack was obviously the most suitable owner in the United States for this painting.

DOERING: Walk us through the transformation of what had been the Elgin Botanic Garden into Rockefeller Center.

JOHNSON: Columbia held on to the land and began to realize that the land was going to be a pretty valuable piece of real estate. As the city grid rolled up the island, the Middle Road, this country lane was renamed Fifth Avenue. Streets were cut through the land running across Hosack’s old fields of grain and in front of his conservatory. And Columbia leased the land to developers, and by 1870, Hosack’s 20 acres was completely covered by apartment buildings. In the 1920s, that land caught the eye of John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had grown up very near the former garden land.

-Yanka-Kostova.jpg)

Victoria Johnson is an Associate Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College in Manhattan, where she teaches on the history of New York City. (Photo: Yanka Kostova ©)

The neighborhood was noisy. There was an elevated train that was filled with speakeasies. It was not a beautiful neighborhood. And John D. Rockefeller Jr. began dreaming of a new complex of commercial and cultural buildings that would be centered on an opera house. The Great Depression hit. He went ahead anyway, and he built Rockefeller Center. The opera house fell by the wayside in the project but became Radio City Music Hall, and in 1985, Columbia sold the land to the Rockefeller Group for $400 million. The land had been leased the entire time from the 1920s to the 1980s. The land changed hands a couple of times after 1985, but around 2000, it changed hands again for almost two billion dollars. And you can stand in Rockefeller Center today, and if you close your eyes and think really hard into the past, you are standing in the middle of a 20-acre botanical garden.

DOERING: Victoria Johnson is an Associate Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College in New York City. Thank you for your time, Victoria.

JOHNSON: Thank you so much for having me.

Links

American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic

New York Botanical Garden | “Rockefeller Center: Botanical History Underfoot”

Hosackia is a genus of flowering plants in the legume family

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

The generation that followed the “founding fathers” had big shoes to fill. So they founded civic institutions like museums, universities, and its first botanical garden to earn the fledgling republic world respect. Historian Victoria Johnson, author of "American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic," spoke with Host Jenni Doering about the foresighted physician who founded the Elgin Botanic Garden in what’s now Rockefeller Center to advance the study of medicinal plants.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In 1776, fifty-six patriots signed their names to a bold document that planted the seed of a new nation, and men like Franklin, Adams, and Jefferson became the “founding fathers.” Less famous is the generation that followed. The Americans who grew up just as the Revolution unfolded saw that the young, fragile democratic experiment would need civic institutions: museums, universities, and even botanical gardens. The Elgin Botanic Garden was once in the heart of what’s now Midtown Manhattan. It was the life’s work of a well-known doctor and medical botanist, David Hosack. Historian Victoria Johnson has written “American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic.” Victoria, welcome to Living on Earth.

JOHNSON: Thank you. I'm so happy to be with you.

DOERING: So, David Hosack isn't a household name, but it's also clear from your book that he helped shape America in the republic's early years. So, who was he?

JOHNSON: David Hosack was the most famous man most of us have never heard of. If he's known at all, it's for having been the attending physician at the duel with Hamilton and Burr. He was chosen by both men. But that was only one of many, many things he became famous for, including founding the first botanical garden in the new nation. He was the reason that New York became New York in his generation, the premier city for the arts and sciences. He was a founder or co-founder of the New-York Historical Society, Bellevue Hospital, the city's first obstetrics hospital, its first mental hospital, its first public schools, its first school for the deaf, its first subsidized pharmacy for the poor, and on and on and on.

American Eden is Victoria Johnson’s third book. (Image: courtesy of W.W. Norton)

Hosack was a teenager walking through New York City, passing people like Hamilton and Burr and George Washington and Thomas Jefferson on the street in New York City. He grew up as a very young child under the British occupation of Manhattan. He saw heroism and sacrifice all around him, and what does that next generation do that's heroic? If your elders have brought an entire nation into being, what do you do as a teenager, what do you aspire to? If you're David Hosack and many of his peers, you want to make the nation great, you want to build the civic institutions that will make it stable, that will bring it world respect, that will help fellow citizens live happy, healthy lives.

DOERING: How did you come across his story, and what inspired you to write this book?

JOHNSON: I love the natural environment, and as a professor who specializes in the history of organizations, I was fascinated to read a description of a couple of pages of David Hosack and his lost garden at the heart of Manhattan. I read it in a wonderful book about the founding of the much later New York Botanical Garden – that was founded 90 years later in the late 19th century – and that story grabbed me from that first second, and the more I learned about him, the more I realized that he was truly a great forgotten American.

DOERING: And in the midst of all that research, we have the musical “Hamilton” which just exploded. And he had this connection with Hamilton. Can you talk a little bit about that?

JOHNSON: Yes, in 1797, so seven years before the duel, Hosack had been called in to a dire situation facing the Hamilton family. Hamilton's son Philip was stricken with a terrible fever, and Hosack saved Philip Hamilton's life by doing some unusual risky things for the time which involved drawing a steaming bath and sprinkling in Peruvian bark, a botanical remedy. Normally, the choice would have been bloodletting or mercury or cold cloths to try to lower the fever. And when Hosack had gotten Philip out of danger, he retired to a bedroom in the house. He wanted to stay in the Hamilton house to make sure that Philip was all right. And he fell asleep, and he woke up suddenly to find Alexander Hamilton at his bedside, kneeling, with tears in his eyes. He took his hand and thanked him for saving the life of his very precious eldest son Philip. And that episode earned Hosack Hamilton's trust and gratitude, and Hosack became Hamilton's family physician.

David Hosack with his botanical garden in the distance (now Rockefeller Center), by Charles Heath, engraving, 1816. Collections of the National Library of Medicine.

DOERING: Hosack seemed to have this faith in botanicals and plants to help with medical remedies. How revolutionary was that? And where did he get that from?

JOHNSON: There was some attention to botanical remedies among doctors with whom Hosack studied, when he studied in New York and in Philadelphia as a very young man. But they were mostly thought of as supplies to be bought at apothecary shops. A lot of the medications were imported, such as Peruvian bark, the most powerful of the contemporary medicines. And they were also used in conjunction with much more radical and sometimes deathly treatments like mercury, which is toxic. And American medicine was still far enough behind European medicine that many of his doctors had trained in Great Britain. So, he decided to sail to Edinburgh himself. It was there that he discovered his life's other great passion – botany. He discovered that Europe was blanketed in botanical gardens, and that for European doctors and medical professors, botanical gardens were laboratories, classrooms, and encyclopedias, all rolled into one. That was where you trained students in medical botany. But what Hosack learned, in addition to falling in love with botany, he learned that no one really knew how to isolate, how to identify new plant-based medicines. And when he returned to the United States two years later, after a full year of daily medical botany training, he was obsessed with the idea that the North American continent was blanketed in undiscovered medicinal plants.

DOERING: So, he comes back to the United States and begins practicing medicine. What does he do next?

JOHNSON: Hosack was appointed a professor of botany and medicine at Columbia [University] shortly after he returned, and he taught his students as best he could out of books, taught them medical botany. He told his students that a doctor must know his foods and medicines from his poisons, but he felt incredibly frustrated that he couldn't teach his students using actual plants. So, he lobbied Columbia for funds to launch a botanical garden, and they said yes, but they were pretty cash-strapped. Finally, he just bought 20 acres of land with his own money. He went three-and-a-half miles north of New York City to buy this land to rural Manhattan, and he would ride up this country lane called the Middle Road into rolling hills, farms. The woodlands of Manhattan had largely been cut down, but there were still groves, and he could see both rivers and mountain laurel and wild grasses and wild flowers. It was completely pastoral, and he decided that if he launched the garden by himself, his fellow citizens would eventually come to their senses and make it truly a public garden.

DOERING: So, I'm wondering what came of his vision to create this botanical garden where physicians could study the medical properties of plants. How useful did it become?

JOHNSON: The garden – it brought Hosack great renown. And Hosack accomplished several things with the Elgin Botanic Garden. He trained an entire generation of doctors not only in how to care for their patients and the medical uses of particular plants, but he also taught them the scientific method.

The portrait Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull, oil on canvas, 1806. David Hosack was Hamilton’s friend and physician, and tended to him after the fatal duel with Aaron Burr. (Photo: Collections of the National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

He trained them in such a way that when medicine moved on after his death more towards the chemistry laboratory and away from botany, he had equipped a whole generation of medical researchers in how to pursue their questions and find answers. He also brought in to being a generation of a professional American botanists where there had been pretty much none before. Most people studying botany in the early republic were gentleman polymaths or they were sort of collectors collecting for nurseries for commercial purposes. And it was Hosack's students and their students who went on to found botanical gardens across the country. The founders of the great New York Botanical Garden were students of Hosack's prized students – so, Hosack's intellectual grandchildren. So, the New York Botanical Garden was founded in the 1890s, and he is present everywhere you go in the garden today, the New York Botanical Garden. The devotion to collecting plants from all over the world, to understand ecosystems around the world, to education of New Yorkers and international visitors… He is everywhere there – his spirit and what he dreamed of – and I love walking around that glorious garden and thinking how happy Hosack would be if he could see it.

DOERING: It was so heartbreaking reading about the collapse of Elgin, this dream and this paradise, this American Eden that he had built in what was then the country of Manhattan, but what is now Rockefeller Center. Why did it happen? Why did it collapse? And what did that mean to him and to his fellow Americans who wanted this garden to be successful?

JOHNSON: He did have a moment of triumph where he managed to get public funding. He lobbied for an entire decade to get the state of New York to take it over and run it as a public institution. He was in debt constantly, but he kept pouring his own money into this institution because he believed in it so much. And he eventually spent more than a million in today's dollars on it out of his own pocket. So, he did have this pinnacle of success in around 1810. He was able to persuade the state of New York to pass an act purchasing the garden to run for the public benefit.

Hosackia stolonifera (Creeping-Rooted Hosackia), from Edward’s Botanical Register, vol. 23 (1837).

So, he actually triumphed. He got what he had always wanted, which was not to build a garden for his own glory but to build a garden for his fellow citizens. The aftermath of that is the garden was given to Columbia College to run for the public benefit. Hosack soon realized to his horror that Columbia wasn't committed to maintaining the garden, in part because of its incredible expense. The garden collapsed. They looked the other way while the caretaker took plants and sold them downtown in a shop, and the conservatory fell apart. The glass panes shattered on the floor, and his arboretum was ripped out and carried up the island to beautify a new insane asylum that was being built. So, he watched the garden fall apart, and this was incredibly painful to him. But he had a great sense of humor and he also had a great sense of drama. And after trying over and over to get the garden back from Columbia – to lease the land back and recreate the garden – he made a purchase which, I think, was his way of saying, I'm moving on. He purchased from a young friend one of the most famous paintings from American history, the “Expulsion from the Garden of Eden” by Thomas Cole. And Cole was a young painter at the time trying to sell this painting, and Hosack ran into Cole in the street shortly after he had finally given up on getting the garden back, and he made Cole an offer on the spot. And Hosack was obviously the most suitable owner in the United States for this painting.

DOERING: Walk us through the transformation of what had been the Elgin Botanic Garden into Rockefeller Center.

JOHNSON: Columbia held on to the land and began to realize that the land was going to be a pretty valuable piece of real estate. As the city grid rolled up the island, the Middle Road, this country lane was renamed Fifth Avenue. Streets were cut through the land running across Hosack’s old fields of grain and in front of his conservatory. And Columbia leased the land to developers, and by 1870, Hosack’s 20 acres was completely covered by apartment buildings. In the 1920s, that land caught the eye of John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had grown up very near the former garden land.

-Yanka-Kostova.jpg)

Victoria Johnson is an Associate Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College in Manhattan, where she teaches on the history of New York City. (Photo: Yanka Kostova ©)

The neighborhood was noisy. There was an elevated train that was filled with speakeasies. It was not a beautiful neighborhood. And John D. Rockefeller Jr. began dreaming of a new complex of commercial and cultural buildings that would be centered on an opera house. The Great Depression hit. He went ahead anyway, and he built Rockefeller Center. The opera house fell by the wayside in the project but became Radio City Music Hall, and in 1985, Columbia sold the land to the Rockefeller Group for $400 million. The land had been leased the entire time from the 1920s to the 1980s. The land changed hands a couple of times after 1985, but around 2000, it changed hands again for almost two billion dollars. And you can stand in Rockefeller Center today, and if you close your eyes and think really hard into the past, you are standing in the middle of a 20-acre botanical garden.

DOERING: Victoria Johnson is an Associate Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College in New York City. Thank you for your time, Victoria.

JOHNSON: Thank you so much for having me.

Links

American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic

New York Botanical Garden | “Rockefeller Center: Botanical History Underfoot”

Hosackia is a genus of flowering plants in the legume family

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth