Global Warming to Worsen Southern Poverty

Air Date: Week of August 3, 2018

Airman 1st Class Jeffrey Albright beating back the heat wave at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. (Photo: Master Sgt. Jason Edwards [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

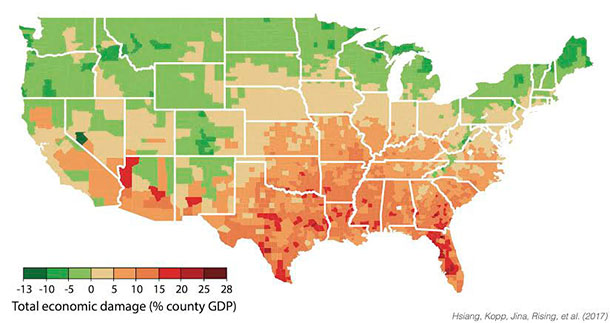

An interdisciplinary effort analyzed vast amounts of climate and economic data to forecast certain regions of the United States will be hit harder than others by global warming. Economist and lead author Solomon Hsiang of the University of California, Berkeley, told Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood the study estimates southern counties of the US, many of which are poor, could face a 20% decline in economic activity if carbon emissions continue unabated through the 21st century.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

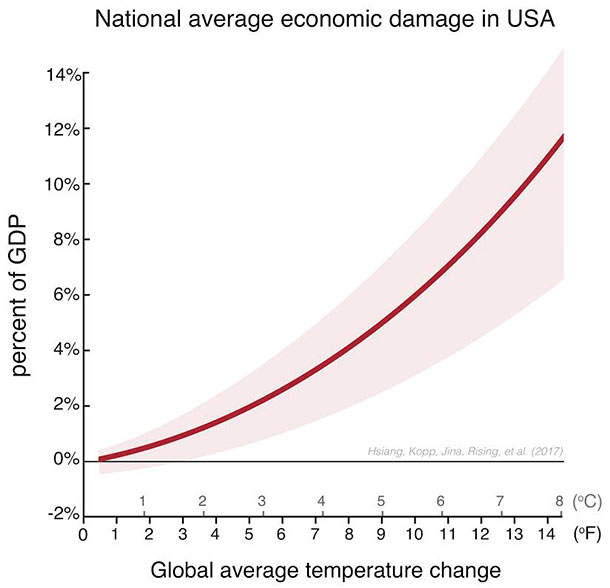

Global warming is on track to devastate the US economy in years ahead if temperatures are allowed to rise unabated, this according to a study published in the journal Science.

Economists based at the Climate Impact Lab in Berkeley, California project that the poorest third of counties in America would be most harmed, with incomes cut as much as 20 percent. The Lab is a consortium of experts from the Universities of California, Chicago, Rutgers, and the Rhodium Group, and this forecast used a wide variety of climate models and economic data. Economist Solomon Hsiang was one of the lead researchers. He teaches public policy at UC Berkeley and joins us now -- welcome to Living on Earth!

HSIANG: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Now, which regions of the United States does your study predict will be hit hardest in this climate disruption scenario?

HSIANG: That’s actually one of the most interesting and surprising findings of this study. What we found is that the southern United States, southern parts of the Midwest, and also the Atlantic coast are some of the most hardest-hit parts of the country. There's a pretty good explanation for that once we did the analysis and we understood was going on. What happens is that the economic impact of warming is much worse if you are already pretty hot. So you can imagine going from 90 to 95 degrees is a much bigger deal going from 70 to 75 degrees, and so because the southern parts the country are already so warm a bit of warming does a lot more harm to them than to the northern parts of the country that tend to be cooler, and in some cases even, you know, the north can benefit. Places along the border with Canada are so cold that they’re actually, they have people who are getting sick from it being so cold, and this is an important finding because the northern parts the country tend to be wealthier today and the southern parts of the country tend to be poorer. So, by hurting the south more you're really hurting the poor population in the country relatively more, and this we think means inequality within the country could actually worsen.

Climate Lab study prediction of economic damage by U.S. County. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Maclay)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about that inequality. How much money are we talking about here?

HSIANG: Well, we're talking about places in the south that could possibly experience losses between 10 and 20 percent of their income in sort of a central case. Now, it's very hard to predict the future, so what we've done is we’ve actually thought about is actually a range of different scenarios that might occur, and so in some cases it gets actually much higher than that, and in some cases it gets lower, but the central case for the south - large swath of the south – to lose between 10 and 20 percent. And that's a lot, that’s actually be much worse than what was experienced during the Great Recession in the United States and it's not that different from what parts of the Midwest experienced during the dustbowl.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about those regions that you say will have modest benefits. It sounds like they are going to be making more money.

HSIANG: So, there are parts of the United States that could benefit from some warming, although those gains are more hazy in the data becomes they’re sort of mild benefits, but those are areas where you might save because you don't have to heat your house as much if things get a little bit warmer. So, those are places in the Rockies or along the northern border with Canada as well as New England. We looked at all different aspects of the economy and there's one place where the north actually gets hit worse than the south.

CURWOOD: Oh?

HSIANG: [LAUGHS] When you look at property crime. It turns out that the only way that the climate really affects property crime rates across the country is that when it's really cold and there's a lot of snow on the ground, nobody goes out and takes each other's stuff. No one steals a car if it's covered in snow. And so, right now, the north gets a lot of cold days and a lot of snow that protects it from this type of impact, but in the future, as things warm up it loses that protective cold, and so you actually see property crime rates rise in the north, but essentially nothing happens in the south.

CURWOOD: What about violent crime rates in your scenario?

HSIANG: So, we also studied violent crime, and violent crime responds to the environment very differently than property crime. We actually see that if you warm up populations - and this is actually true outside the US as well - we see violent crime rates go up very steadily pretty much for everyone. It doesn't matter what your initial temperature is. So, we see violent crime rates rise by about five percent across the entire country.

CURWOOD: So looking at some of the maps and charts that you have with your study, it looks like south Texas and Florida are really going to be in trouble in a warming scenario. How much trouble exactly for those places would you predict?

HSIANG: Those are the parts of the country where you could be seeing counties losing upwards of 20 percent of their income and that's due to the combination of what we talked about before, that those places are really hot and so getting hotter is extremely costly. But there's an additional issue that arises along the Gulf Coast which is the effects of sea level rise interacting with hurricanes, and so places like Texas, Louisiana and Florida end up having really large costs along their coastlines due to the fact that as the sea level rise goes up, the storms that arrive are going to have bigger surges, and in the future we expect to have a changing pattern of hurricanes where sometimes there will be more of them and sometimes they will be stronger, and so that can increase the economic losses you know, year over year for those reasons quite substantially.

Climate Lab study forecast of national average economic damage in the U.S. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Maclay)

CURWOOD: So, your research then is indicating in a general way as well as those specific places that the regions that are going to have the most economic damages from climate disruption are presently very politically conservative strongholds. To extent do you think your research might be able to, well, change the discussion with those lawmakers and their constituents?

HSIANG: Well, first just to be clear, all of our work was completely unrelated to the current political landscape. We've been working on this for many, many years. We didn't know these types of results until now, so the fact that people may not have taken these economic consequences into account in making their previous judgments about or in terms of how much they're concerned about climate change, maybe that's OK. Nobody knew that this was going to be what we saw in the data, but what we're hoping is that now the public can have a well-informed dialogue about how we want to manage the climate based on what we can see at least at this point about what might be lying ahead.

CURWOOD: So, how can you research be used to come up with, say, a more accurate social cost of carbon, a metric that can inform, perhaps, legislation, maybe carbon tax, other types of policies.

HSIANG: Yeah, and a lot of our work is exactly aiming at trying to inform the social cost of carbon. The social cost of carbon doesn't just reflect what people in Oklahoma or in California are going to feel. It also reflects the fact that when I drive my car here in California, the carbon dioxide goes up into the atmosphere, circles the planet over 80 times and is affecting people all over the world, and so we are undertaking a major effort to take what we've learned from this analysis and expand it to the whole world and then we'll be using those numbers to compute the social cost of carbon that could be used by regulators in any country really, not just the United States. This analysis, we show that the southern United States is the most heavily impacted because it’s hot relative to the north, but if you keep going south it just keeps getting hotter and hotter. So you think about Mexico, Central America, these places are going to experience these things we even more intense than the American south, and so it's really important that we understand what’s coming ahead for them and that we account for those losses to the global society.

CURWOOD: What about population increase? Here in United States we go from roughly 300 million people at the turn-of-the-century back there in the year 2000. By the middle of the century, it's projected we’ll be over 400 million people. The effects of climate disruption, reducing the economic prospects of folks in the south plus this population rise equals what, do you think?

Solomon Hsiang is an Associate Professor of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Maclay)

HSIANG: Yeah, so one of the major challenges in economics generally as a field is just how do we maintain living standards and well-being for a population that's growing. It takes more resources to support more people moving ahead into the future and so what you try to do is maintain economic growth, which allows us to produce more material assets at least as fast as the population is growing, because if you just have more people in a place with a same number of material assets, then you have to start subdividing them more and more and more and everyone becomes a little poorer. What climate change does is it actually slows down the economic growth rate. It puts like a handicap on us in this race between economic growth and population growth, and so it makes it even harder for us. We have to be even more innovative. We need to work harder, and so what I think climate change is going to do is it’s going make it a lot harder to meet the standards of living that people expect, particularly in the regions that are hardest hit. So, people really dislike having long periods of unemployment or having long recessions, and one way I’ve put it to some folks is that climate change imposes something that's on the scale or sometimes bigger than a recession except it doesn't just go away, it’s not like we just recover from it. Once you have it, it's here to stay and so we think about whether or not we can make changes today that will avoid those types of outcomes and those are the types of questions we should be asking ourselves.

CURWOOD: Solomon Hsiang is an economist and Associate Professor of Public Policy of the University of California, Berkeley. Thank you so much Professor for taking the time today.

HSIANG: Thanks for having me.

Links

The study in Science: “Estimating economic damage from climate change in the United States”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth