Resilience In Puerto Rico’s Tropical Forests After Hurricane Maria

Air Date: Week of September 14, 2018

The decimation of mangroves along the Puerto Rican coastline after the hurricane in 2017. (Photo: Courtesy of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

When Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico in 2017, the direct hit turned a green island brown. Vast areas of forest were defoliated, or stripped of their leaves and branches. From mangroves to cloud forests, every ecosystem on the island was devastated by the massive storm, but as Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports, forests that evolved in the hurricane belt have ways to cope and are coming back.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

As the US struggles with the second catastrophic hurricane season in a row, through this month we are looking at the aftermath of 2017’s deadly Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Along with the thousands of lives lost and countless homes and businesses destroyed, the intense winds and rains wreaked havoc on the natural environment.

NASA scientist Doug Morton had a bird’s-eye view of the effects of the storm on the island’s forests with the cameras from the Goddard Space Flight Center.

MORTON: Some of the most striking images following hurricane Maria were looking up at El Yunque National Forest from the ground below and seeing nothing but brown on what had been this brilliant green hillside. It’s almost like you took a tropical rainforest and you turned it into a New England woodland in December because you stripped off all of the leaves off almost all of the trees. The canopy literally went from green to brown.

BASCOMB: But of course, the plants and animals native to Puerto Rico evolved with hurricanes, so they have built-in ways to recover. As part of a trip I took to Puerto Rico 9 months after the hurricane I caught up with scientists who are documenting the destruction and resilience of nature.

An aerial shot from before Hurricane Maria tore through this forest. (Photo: Courtesy of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

[BIRDSONG]

BASCOMB: Are you Maria?

RIVERA: Yes. Nice to meet you.

BASCOMB: Nice to meet you, I’m Bobby.

BASCOMB: Here in El Yunque, this tropical rainforest is a gold mine of scientific research. Government scientists, like biologist Maria Rivera, have been maintaining research plots here for decades.

I met Maria at the Forest Service office building just past the entrance to El Yunque.

Dressed in the khaki and green uniform of the US Forest Service, she has been coming here once a week to collect data for the last 18 years. But she says she was shocked when she first saw the forest after the hurricane went through.

RIVERA: My first reaction was a bomb inside the forest.

BASCOMB: A bomb.

RIVERA: Yeah.

[SFX DRIVING SOUND]

BASCOMB: I tag along with Maria as she heads out in a Forest Service jeep to collect temperature, rainfall, and biomass data from her 24 experimental plots in the forest.

But first we must stop to check in with a Forest Service colleague with a clipboard. Maria rolls down the window to give her name and the time.

[DRIVING SOUND]

RIVERA: Buen Dias, Maria Rivera. Si. Nueve Catorce [9:15]. They take the time when you pass for safety.

BASCOMB: If we don’t return here by the end of the day Forest Service employees will come to look for us.

When I visit the park most of it is still closed to visitors.

Many roads are impassable with branches and tree limbs scattered about and some deforested hillsides are still unstable.

[SOUND OF CAR STOPPING]

It’s a good time to be a mangrove sapling on the coast of Puerto Rico. The hurricane heavily damaged or killed nearly all the mangrove trees in some areas of the island, but tiny saplings take advantage of the new sunlight and space to grow. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: We stop next to a huge landslide on the side of the road.

The ground is bare but for rocks and dead trees.

RIVERA: Look to the left. A lot of branches and the tree are dead.

BASCOMB: So, everything here is dead. It’s all brown and twisted and gnarled and pulled out from the ground even. It almost looks like a forest fire went through here.

RIVERA: Uh huh…

BASCOMB: She says the entire forest looked like this right after the hurricane struck.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We start the day at the very top of Luquillo mountain, some 3500 feet high, in a cloud forest.

RIVERA: This is my favorite area.

BASCOMB: It’s chilly, at least 20 degrees cooler than just a mile or so down the mountain.

The forest here has an ethereal quality. Wispy clouds settle around the trees like a damp blanket.

This area gets upwards of 200 inches of rain a year and is typically dripping with life.

Maria says before the hurricane struck nearly every surface in this forest was covered with moss and epiphytes growing in the crook of trees, but today it is nearly bare.

RIVERA: Very different, very different with the path for the hurricane. But recover, this is the nature! [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: She says these short, stout, trees evolved to cope with high winds at the top of the mountain.

They were a small target to begin with, and when the hurricane blew through they simply dropped their leaves and weathered through the storm.

Very few trees here were actually uprooted and killed.

Still, when she came here about 6 months after the hurricane, Maria says she was stunned to see how the trees responded.

Biologist Maria Rivera in the cloud forest at El Yunque National Forest (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

RIVERA: When I make a measure for [after] the hurricane, all trees they have flowers. It was very pretty. Not much leaves but when I see the flower I say, wow this is great.

BASCOMB: Across the entire island, trees set flowers and fruit outside their usual season.

It’s a stress response and survival mechanism to pass on their genes.

In a closed canopy forest the competition for sunlight can be fierce, but after a hurricane opens new space trees are in a race to drop seeds and fill that vacated spot.

[CAR DOOR SLAMS]

BASCOMB: We pile back into the Forest Service jeep and head just a few minutes down the mountain to a completely different ecosystem.

RIVERA: I’m going now to the palm area. It’s a different ecosystem, it’s palm.

BASCOMB: From the road near the top of the mountain we get an expansive view of the valley just below us.

From above the closed canopy of a tropical forest typically look a bit like broccoli.

But this forest looks more like spears of asparagus.

The trees have mostly grown their leaves back, but they are skinny with very few branches.

Maria says that’s how the palm trees were able to survive the hurricane.

RIVERA: The palm here, they don’t have branches.

BASCOMB: So, clinging to the side of the mountain, the wind just passed through the skinny palm trees.

But if a palm loses the branches it does have at the very top of the tree it will die, which is what happened to about 50 percent of the trees here.

They were decapitated.

The dead trees still standing look like matchsticks.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We drive another 5 minutes down the mountain and come to yet another ecosystem.

RIVERA: This is the area of dry forest. Do you see to the left, do you see the trees?

BASCOMB: They’re all twisted.

RIVERA: Uh huh!

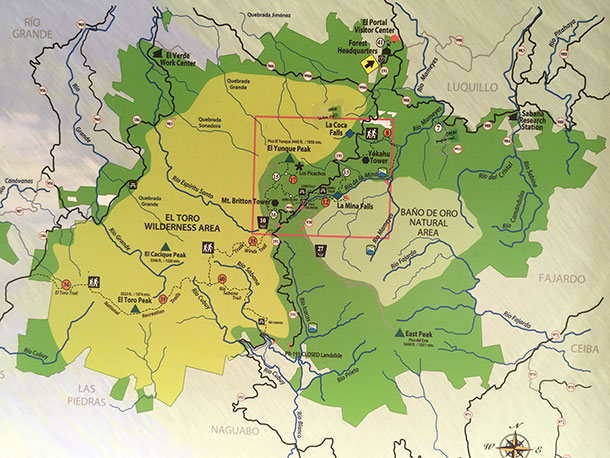

A map of El Yunque National Forest. Most of the park was closed to visitors after the hurricane. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: So, the hurricane literally twisted the trunk of the tree itself.

RIVERA: Yes, yes, yes, yes.

BASCOMB: Wow.

[CAR DOOR CLOSES, WALKING SOUNDS]

RIVERA: So, this is the plot, the dry forest.

BASCOMB: Wow, it’s much hotter here.

RIVERA: I think 20 or more.

[BIRD CALL]

BASCOMB: Easily.

RIVERA: Yeah, yeah.

BASCOMB: The palm forest still looks quite devastated there. You don’t see the epiphytes growing on the tree trunks. It still looks like match sticks with just a little bit of growth growing out of the top of the palms. But this forest, it looks pretty green here. There are a lot of leaves, a lot of branches.

RIVERA: Yeah, yes. That point is ok. The recovery was very fast here.

BASCOMB: Maria says the old, weak, branches broke off, but healthier parts of the trees stayed intact and their leaves grew back quickly.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: To see the most heavily damaged ecosystem we head down the mountain again to the coast, where the hurricane first made landfall.

RIVERA: This is mangrove.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: The mangrove forest is hot and sunny.

Maria says the ground was still covered in 10 inches of water the first time she came here after the hurricane.

Nearly all of the 50-foot-tall trees around us appear to be dead.

RIVERA: When I come here the first time I think all are dead. They don’t have leaves. They don’t have new growth.

BASCOMB: Mangroves make their living at the salty edge of the sea.

They thrive in salt water and are designed to withstand strong winds, so researchers were surprised to see that nearly all of the mangroves looked dead after Hurricane Maria came through.

After Hurricane Maria many palm trees were left looking like matchsticks. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

Those biologists surmise that the salt water and sand blown against the mangroves essentially burned all the leaves and branches.

RIVERA: And do you see the sand here?

BASCOMB: Oh, on the side of the tree.

RIVERA: Yes, yes.

BASCOMB: But mangroves evolved to live in this harsh coastal environment in a region prone to hurricanes.

Maria Rivera points to some green shoots poking out at the bottom of a tree next to us.

RIVERA: Do you see? Down, down.

BASCOMB: See, that’s the thing, the tree itself looks dead but it’s not because it has these new shoots coming out from around the base of it.

RIVERA: Correct, correct. This is, I mention to you when I come the first time, I say all are dead. No! Not all are dead, they continue.

BASCOMB: The mangrove forest was the most devastated ecosystem on Puerto Rico, but given enough time, they will recover.

And since no other plant can easily grow in this harsh ecosystem they have no competition. Indeed, adding to the shoots on existing trees, a carpet of foot tall mangrove saplings covers the sandy ground.

[CAR SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: The recovery of Puerto Rico’s forests shows the value of a long-term study.

Over at the University of Puerto Rico’s Botanical Garden I met up with Ariel Lugo, director of the International Institute for Tropical Forestry

He says forest regrowth is exceptionally high following a devastating hurricane.

LUGO: The productivity of the forest right now is higher than it was before the hurricane.

BASCOMB: He says hurricanes can have both positive and negative effects on an ecosystem.

The palm forest in El Yunque National Forest. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

LUGO: In the first five years after the hurricane, what we found after Hugo was the fastest primary productivity that we've ever measured in the forest. When you destroy the canopy and you have to regrow that structure, the rate at which the forest regrows, which is a measure of its productivity, is the highest that we've ever measured before the hurricane, and it compares favorably with the rate of plantation forestry.

BASCOMB: He worries most about the slow pace of the mangrove recovery, specifically that they won’t likely be there when the next hurricane strikes.

LUGO: So, who is going to absorb the energy of the hurricane? Well, it’s going to be absorbed by structures, by human structures, and it’s going to be absorbed by other parts of the landscape, and so you are liable to see more landslides, and you're liable to see greater floods, etc.

BASCOMB: In the long term Lugo thinks the storm will be a recalibration.

Fit plants and animals will survive.

Older, weaker, less adapted and invasive species will not.

He estimates that the forests will need roughly 60 years to recover completely and the impacts of the hurricane raise enough questions to keep scientists like Maria Rivera busy for decades.

But for Maria, it’s more than just collecting data. She says seeing the devastation of the forest she knows so well was difficult at first.

RIVERA: The first impression was cry. I work here for 27 years. It was the first time when I see the devastation. But now is different now. For me now when I see the trees, when I see the green area, the feeling is different. I’m happy for that. I’m very happy.

CURWOOD: Thanks for that report, Bobby.

BASCOMB: Sure, Steve. You know, I actually came across another story in the course of my reporting from El Yunque. The timing didn’t work for me to check it out while I was there but I did speak with the researcher when I got back.

CURWOOD: Great, what’s the story?

BASCOMB: Well, Tana Wood is a lead scientist with a group called the Tropical Responses to Altered Climate Experiment, or TRACE, and she’s looking at how climate change might impact tropical forests.

CURWOOD: Cool, how are they doing that?

BASCOMB: They have 3 experimental plots in El Yunque National Forest. They set up infrared heaters there to actually raise the temperature of the forest 4 degrees Celsius, or about 7 degrees Fahrenheit, that’s the median temperature increase projected for the tropics by the end of the century. They want to see how tropical forests respond. Here’s Tana Wood.

Mangrove forests were a first line of defense against the hurricane, and were the most heavily damaged type of forest. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

WOOD: We set up the experiment three years ago. We had one year of data collection that we did prior to starting the experiment, just to get what our baseline was. And then we started warming for a year and then the hurricane hit.

CURWOOD: Wow, so that must have thrown their experiment into chaos.

BASCOMB: It did for a while, but Tana says that now they actually have an even more interesting experiment. How do the tropical forests of a future, warmer planet, respond and recover after a hurricane?

CURWOOD: Ahh, right! What did they find?

BASCOMB: Basically, the warmer forest is slower to re-grow and sprout new saplings than their control plots. They also found that the warmer plots are sequestering less carbon dioxide.

WOOD: What we were starting to observe in our warmed plots, as part of the acclimation process, they were not photosynthesizing as much, which would mean less carbon coming into the plants and less carbon that could go into the roots.

BASCOMB: But, Steve, Tana Wood is quick to point out that even though the warmed forest isn’t doing quite as well as the control forest, this is still actually a positive news because the forest didn’t just die all together, it is able to recover.

WOOD: They’re coming back from the hurricane. The system seems able to respond. So the fact that they’re acclimating could mean, could be good news for the future of these forests.

CURWOOD: Well, thanks for that update, Bobby. And I’m looking forward to your next installment on the impacts of Hurricane Maria.

BASCOMB: Thanks Steve, you’re welcome.

Links

International Institute of Tropical Forestry

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth