Getting Hormones Out Of Wastewater

Air Date: Week of November 2, 2018

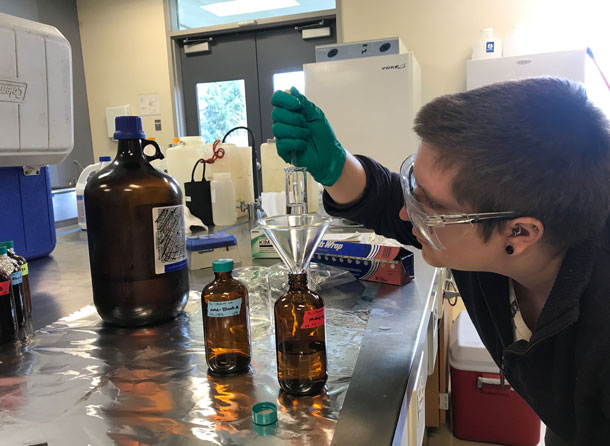

Postdoctoral Researcher Carolyn Hutchinson tests a water sample in the lab. (Photo: Ari Daniel)

At a wastewater treatment plant, sophisticated filtration and sanitization methods aim to remove pharmaceuticals, microplastics and chemicals. Human waste also contains various hormones, which can stick around in the environment and harm other creatures, and now there are new ways to get hormones out of the water. Ari Daniel reports from a wastewater treatment plant in Salem, Oregon on how this works.

Transcript

CURWOOD: On the other end of the municipal water system is sewage. Our modern world simply wouldn’t be the same without wastewater treatment, which keeps much of the yuck we produce out of streams, rivers, lakes and oceans. And it’s a tall order, because people put a lot of stuff down into sewers, including pharmaceuticals, microplastics, and chemicals that standard treatments fail to filter out. And human waste contains various hormones, though there are ways keep them out of the environment.

Ari Daniel visited a plant in Salem, Oregon to find out how.

DANIEL: It’s hot out. So you take a shower. Or you fire up the grill. And after eating a burger, you wash your plate off. And then, later, you flush the toilet. All that water — it just… goes away. Gurgles down a drain into the pipes. But that’s hardly the end of the story. That water gets cleaned up so it can tumble back into a river or stream. And it turns out that the process may inadvertently help clear the water of potent hormones.

The big stuff, that’s easy to filter out of the 45 million gallons of water flowing through the Willow Lake Wastewater Treatment plant in Salem, Oregon every day.

EISNER: There’s a lot of little McDonald’s toys that come through, little kids flush down the toilet.

DANIEL: Stephanie Eisner — operations manager here — says they also get a lot of lumber and tires showing up.

DANIEL: That’s getting flushed down the toilet?

EISNER: Well, most likely, somebody pulled a sewer manhole in the road and stuck tires in there.

A series of long, narrow rectangular pools where treated wastewater is disinfected and exposed to sunlight, which can degrade chlorinated estrogens. (Photo: Ari Daniel)

DANIEL: After the toys and tires get screened out, what remains is dirty water.

EISNER: Right now, we’re right by our south digester complex.

DANIEL: We are walking amongst sewage?

EISNER: So there’s pipes below us, yes, that would be having wastewater flowing through it. We try to remove as much of the pollutants that we can.

DANIEL: That removal takes place, in part, in clarifiers — that look like giant circular swimming pools. Solids settle out and can be removed, and greases float to the surface where they can be skimmed off. Separately, bacteria eat away a lot of the gunk in the water. And then, the final step, says Dave Griffith, an environmental chemist at nearby Willamette University —

GRIFFITH: This is the disinfection basin in front of us, and it’s a really important part of wastewater treatment. You kill anything that’s pathogenic.

DANIEL: The plant disinfects the water by chlorinating it. Griffith’s got his eye on this chlorination step… because chlorine is reactive, so dumping it into the water here means creating a raft of new chlorinated compounds.

[WATER SOUNDS]

We stand above a surging spray of water that’s about to leave the plant and enter the Willamette River.

GRIFFITH: Alright, shall we grab a sample?

HUTCHINSON: We should.

DANIEL: Griffith and one of his researchers, Carolyn Hutchinson, lower a pail into the froth below. They’re collecting water samples in search of estrogen.

HUTCHINSON: Estrogen is a very potent steroid hormone.

DANIEL: Everyone — you, me, your neighbor — excretes estrogens, so they find their way into our wastewater.

HUTCHINSON: One big effect is it feminizes fish populations.

DANIEL: That’s right — it feminizes fish. Which means turning all fish in a population — including the males — into females. And that can lead to a collapse of the fish stock.

HUTCHINSON: It also affects amphibians, birds, even mammals.

DANIEL: Estrogens react with chlorine, and Griffith wants to know what happens to the estrogens here after the chlorination step.

GRIFFITH: That basin over there where the chlorination happening is exposed to the sunlight.

From left, Carolyn Hutchinson and Dave Griffith at the Willow Lake Wastewater Treatment Plant in Salem, OR. (Photo: Ari Daniel)

DANIEL: I follow Griffith’s gaze to a long, narrow rectangular pool. It’s uncovered, which isn’t the rule. Due to odor and other reasons, not all treatment facilities expose the water to sunshine. But the UV radiation from sunlight introduces an unexpected — and free — benefit.

GRIFFITH: One intriguing thing that we found is that the chlorinated estrogens degrade much more quickly under sunlight than the regular estrogens. Before they even get to the end of the basin.

DANIEL: In other words, they’ve degraded before the water exits the plant and returns to the river.

EISNER: That’s good news.

DANIEL: Stephanie Eisner again.

EISNER: So it might make some people change the way they do things.

GRIFFITH: Our goal is that we can inform how we treat wastewater in a more cost effective, overall a better way.

[BOAT MOTOR RUNNING]

DANIEL: A couple miles away, a small boat speeds along the Willamette River. Dave Griffith is aboard.

GRIFFITH: So, there it is right over there.

Treated wastewater flows into the Willamette River and gets diluted. (Photo: Ari Daniel)

DANIEL: He points to a spot in the water near the tree-lined shore. It’s where the water from the treatment facility flows into the river and gets diluted.

GRIFFITH: So we’re gonna go just downstream of this point to get a sample of basically river water and wastewater mixed together.

DANIEL: This is where Griffith can measure how many estrogens there are in the real world. Which will tell him just how effective the degradation of these hormones has been.

GRIFFITH: If we understand better the mechanisms here and in the wastewater treatment plant, we can better predict what’s happening in any other river situation where you have a wastewater treatment plant discharging water.

DANIEL: Estrogens are just the beginning. Because Griffith’s curious about the interplay between chemicals and our liquid environment more broadly.

GRIFFITH: There’s not a chemical out there that you make, produce, use that doesn’t end up in the environment in some way or another, whether it’s accidental or intentional.

DANIEL: Griffith pauses, the boat hovers over its waypoint, and the water sampling begins in earnest.

[WATER SOUNDS]

Nearly all the water flowing past the boat today won’t end up in one of Griffith’s glass containers. It’ll snake northwards, connecting with the Columbia River, where it’ll surge west, ultimately flooding out into the Pacific. Until eventually, one day, it may once again find itself inside your home.

CURWOOD: That’s Ari Daniel reporting from Salem, Oregon.

Links

The Willow Lake Wastewater Treatment Plant in Salem, OR

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth