Brazil To Grab Indigenous Lands

Air Date: Week of March 29, 2019

The Amazon rainforest is threatened by mining interests, but under the Brazilian Constitution, indigenous tribes within Brazil have been able to reject development. (Photo: Amauri Aguiar, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

A constitutional crisis looms in Brazil as its new president, Jair Bolsonaro, seeks to open the Amazon tropical rainforest to more development. The country’s native tribes have a constitutional right to reject any development on their territory, but President Bolsonaro recently said he will allow mining on indigenous land without their consent. Sue Branford writes for Mongabay and joined host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the threats mining poses to indigenous culture and the environment.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

A constitutional crisis looms in Brazil as its controversial new president, Jair Bolsonaro, seeks to open the Amazon to more development. Before the 1950s the interior of the Brazilian Amazon was solely occupied by the indigenous tribes who'd been living there for millennia. But starting in the 50s and 60s the Brazilian government began a program to encourage people to settle the Amazon and make it productive.

[PORTUGUESE ANNOUNCER WITH VOICEOVER: It is not enough to build roads. We must colonize for agriculture or for cattle. The land is good. There are green pastures in the forest made of milk and honey. MUSIC FADES]

BASCOMB: The government built a new capital city, Brasilia, at the edge of the rainforest and moved full steam ahead on exploiting the land with little thought for the native tribes living there. Then following the collapse of the military dictatorship, a new constitution was written in 1988, which for the first time gave native tribes legal ownership of their land and the constitutional right to reject any development on their territory. The new president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, recently announced plans to reverse those rights and allow mining on indigenous land, despite protests from native tribes. President Bolsonaro came to power promising to clean up the government after two former presidents wound up in prison for corruption and money laundering. Sue Branford writes about the Amazon for Mongabay and joins me now. Sue, welcome to Living on Earth!

BRANFORD: Nice to be here again.

BASCOMB: So, Brazil's constitution is pretty clear about the land rights of indigenous people. It says that they have an inalienable right to a veto for projects like this. So how exactly does the Bolsonaro administration think that it can go against the constitution?

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro (Photo: Palácio do Planalto, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BRANFORD: Well we're not absolutely clear. I mean, there are various way forwards, it will probably be quite difficult for them to take the correct route, which is really a constitutional amendment, which would have to go through Congress. It's more likely that Bolsonaro will decide on a presidential decree, which will at least allow him some time to overrule the Constitution. I mean, he has got a big majority in Congress, and the agriculture and the mining lobbies in Congress are very strong. So I don't actually think he will have any really long term problem. I think what he's going to confront is a lot of opposition from environmentalists, from campaigners, from the Indians themselves. Because for the Indians to win these rights over their land was a big conquest in the 1988 constitution. It was what seemed to be a sea change, that for the first time, Brazil was recognizing that these original inhabitants had the right to their land and had the right to decide what they were going to do with it.

BASCOMB: What are they planning to mine for and what are the potential environmental impacts of that?

A youth from the Yanomami peoples of the Amazon. President Jair Bolsonaro says he will continue advancing mining interests without the consent of indigenous tribes such as the Yanomami. (Photo: Sam Valadi, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BRANFORD: Well, the Amazon has an awful lot of minerals. It's got big gold reserves, probably the largest in the world. It's got silver, it's got bauxite. There is a lot of mining wealth under indigenous land. And so it is very much this thinking that Brazil has all this mineral wealth that should be exploited by Brazil, they shouldn't not be used just because what they see as a handful of Indians want to conserve it. But this is widely seen in Brazil as a backward way of thinking. That particularly now when we're getting more and more concerned about global warming, there's a growing number of Brazilians who feel that the forest, the Amazon forest, should be conserved, that if we go on, if Brazil goes on cutting down the forest, that Brazil is going to reach a turning point. Because scientists have been saying for many years now that once about 25% of the forest is felled, then you're very likely to spark off a whole process by which the rich tropical forest is transformed into a savannah. And they now say about 21-22% of the forest is felled; so we're very close to the tipping point.

BASCOMB: You know to build a mine, of course, it's not an isolated structure; they will need roads to get to the mines, and that of course means opening up the forest to other activities. There's the famous "fish bone" effect, you know, so if you look from above, and you look down, there's the main road that's been built, maybe it's paved. And then off of that there's all these tributaries of informal roads that farmers, agriculturalists, other miners and things will use. How big of a concern is that do you think?

BRANFORD: That's a very big concern. I remember when they were building the BR-163 Highway, which went from Cuiabá to Santarém, a port on the Amazon, they promised that they would control the influx of population, that there would be none of these lateral roads built off the main highway. And they made a series of projections about what they thought the environmental damage would be. And 10 years later, the damage was off the scale, it was much worse than their worst projection made at the time. It is very difficult to control influx of population once you've got some kind of road, whether that be a highway to join up two cities or whether it be an access road for a big mine. People do move in and there is land hunger still in Brazil, because quite a lot of land is in the hands of the big farmers. There's thousands of landless peasants who see the only way forward, the only way to earn their living, is by occupying a plot of land, so they move in whenever they can, and one can understand why they do it. And this is likely to be more serious now, it's already getting more serious in the Amazon, because Bolsonaro is not controlling the influx of population. He has dismantled FUNAI, the indigenous agency; he's in the process of dismantling IBAMA, the environmental agency. So loggers and small-time miners, they can all move into indigenous land, and the Indians are very much on their own; there's really no institutional forces they can turn to have these invaders evicted from their lands, and so there's been a considerable increase of violence in these areas now.

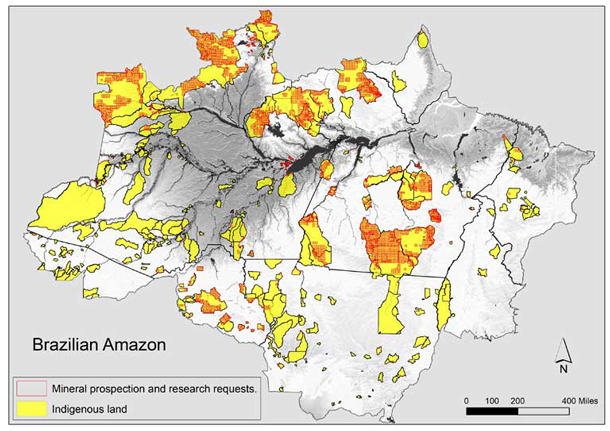

Mining industry and individual prospecting requests on indigenous land as filed with the federal government. (Map by Mauricio Torres with Mongabay, using data provided by the Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral.)

BASCOMB: Can you give me an example, maybe from the bad old days during the military dictatorship, and how mining or this type of development on indigenous lands impacted indigenous people? So, what are these indigenous tribes looking at from their own past to inform them today about making decisions about how to move forward?

BRANFORD: Well I think the project that the Indians talk about most is the big Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River, which is the second largest hydroelectric power station in the world. And the government made a lot of promises to the Indians whose lives have been seriously disrupted by this dam, that they would give them land, they would give them money, they would make sure their lives weren't disrupted. And the government has in fact, given the Indians some money, but a lot of delegations of indigenous people have visited Belo Monte and have come back horrified at what's happening to indigenous culture. Because these people, a lot of their land has been taken away, they haven't got enough space to hunt or even to cultivate crops. So they're basically sitting in villages, getting handouts, food baskets, from the authorities, and their culture is being decimated. And I've heard a lot of Indians say that they can scarcely believe it, the Indians in these villages now have high levels of diabetes, they have strokes, they have all these diseases of the Western world, which many people think come from the food we eat, and that Indians have never had in the past. And it's made them feel they should not really believe the government if the authorities come with promises about the money they will get and all the advantages that will come from these big mining projects. And I think there's nothing like going to an area and seeing the impact of a project to make communities aware of just what could happen to them, what the risk is for them.

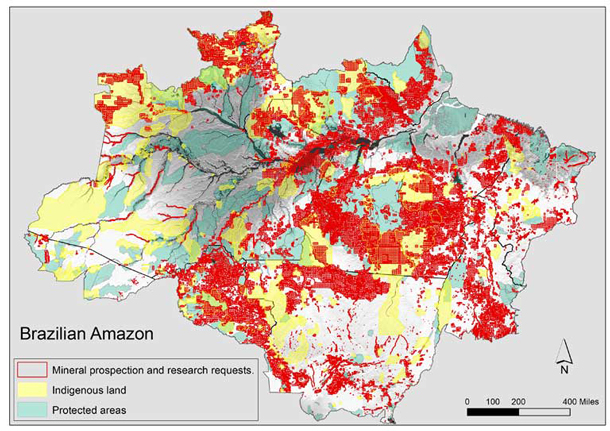

The mining industry has not only made prospecting requests (red) within indigenous reserves (yellow), but also on other conserved lands (green). (Map by Mauricio Torres with Mongabay, using data provided by the Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral.)

BASCOMB: Now, this will have to go through the courts, I believe; what should we be looking for there? How likely is this to get the green light in the courts in Brazil?

BRANFORD: Well, this is an interesting development because the judges, the judicial system in Brazil, which is widely regarded as reactionary, conservative, is actually taking the forefront now in organizing opposition to Bolsonaro. So we've got the General Prosecutor Raquel Dodge, who is the most powerful prosecutor in the country saying, hang on Bolsonaro, we're going to fight this in the courts, we're not going to let you ride roughshod over our Constitution. And there's also the Public Federal Ministry, which is a sort of special bit of the judiciary, which not many countries have, which is not actually part of the official judiciary. It's a kind of independent group of lawyers and they are now saying that they're going to be supporting the Indians and doing everything they can to stop mining happening on their land. So we will see opposition and it will come rather surprisingly, I think, mainly from the judicial system who is not at all intimidated by Bolsonaro.

To begin strip mining, it is necessary to remove all forest and topsoil on site. (Photo: Norsk Hydro ASA, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Sue Branford is a freelance journalist based in London who writes for Mongabay. Sue, thanks for taking this time with me.

BRANFORD: Thank you.

Links

Mongabay | “Brazil to open indigenous reserves to mining without indigenous consent”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth