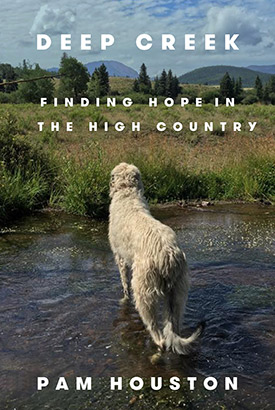

Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country

Air Date: Week of March 29, 2019

Winters at 9,000 feet in the Colorado Rockies can bring low temperatures of 35 below zero. (Photo: Pam Houston)

In her new memoir, “Deep Creek,” writer Pam Houston describes finding refuge in a 120-acre ranch high in the Colorado Rockies. As she cares for her Irish wolfhounds, horses, donkeys, and Icelandic sheep through gorgeous summer days and frigid 35-below winters, and marvels at the local wildlife, the ranch serves as her sanctuary after a childhood of abuse and neglect. Pam Houston speaks with Host Bobby Bascomb about how, even as the changing climate threatens to destroy her beloved ranch with wildfire, she aims to “love the damaged world and do what I can to help it thrive.”

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Writers have often sought refuge in nature and wilderness. In a vast desert or forest, or looking down at the landscape from a mountain peak, trauma and heartbreak can seem so much more distant, and the burdens of the past easier to carry. For writer Pam Houston salvation came in the form of a 120-acre ranch high in the mountains of Colorado. In her 2019 book “Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country” she chronicles 25 years of winters that bring temperatures as low as 35 below, and smoky summers that threatened her ranch with wildfire. Pam has lived through a lot with the land. And she writes about how the place has gradually helped her heal from childhood sexual abuse she experienced at the hands of her father. Pam Houston joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

HOUSTON: Thank you very much!

BASCOMB: So Pam, first of all, tell me about the ranch that's the focus of your memoir, Deep Creek. How did you find the place nearly 25 years ago, and why did you decide to call that home?

“Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country” is Pam Houston’s first memoir. (Photo: W.W. Norton)

HOUSTON: Well, the ranch is 120 acres in a high mountain meadow at 9000 feet. It's got 13,000-foot mountains on all sides of it; fur and spruce forest and aspen. And I went looking for a place to begin with, because I sold a book of short stories, my first book, when I was still in graduate school, and when I got the check for $21,000, my agent said, Don't spend it all on hiking boots. And that seemed like good solid parenting advice. And so I went driving all over the West looking for a place and I got to Creede, Colorado, which was just the next place on the list. A writer friend of mine, Robert Boswell, had said, check out Creede, I heard it's cool. I got there and looked around at some houses and finally got taken out to this ranch, this 120-acre ranch. And it was the third week of September, and if you can't fall in love with Colorado in the third week of September, you can't fall in love. Because the aspens are changing in giant, undulating swaths of Tequila Sunrise colors all over the hillsides, and the sky is blue and the air is crisp. And here was this place, with this hundred-year-old barn with a big beautiful mountain behind it. And my $21,000 represented 5% down on that place. And the realtor said, You know, I think the widow Blair -- who was selling it -- I think the widow Blair is going to like the idea of you. And if you give me your 5% down and a signed hardcover of Cowboys Are My Weakness, I'll see what I can do.

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] Now, the third week in September sounds stunning. But then winter comes --

HOUSTON: [LAUGHS] Right?

BASCOMB: -- and winter at 9000 feet is not for the faint of heart, the way you describe it in your book. You describe a scene where you have a really legitimate concern that you might actually get lost in a blizzard between your house and your barn. Tell me what it's like to live there in the winter, and, you know, how you overcame that?

HOUSTON: Well, it is possible; we can get as much as four inches of snow an hour, the record is 76 inches in 24 hours. There are days when the winds are so high and the snow is so thick that I can shovel my way to the barn and get everybody fed, get everybody hay, get everybody water, get everybody their grain. And sometimes my path to the barn is obliterated by the time I do 25 minutes of chores.

A 100-year-old barn lends character to the ranch and keeps the horses, donkeys, and Icelandic sheep warm. (Photo: Pam Houston)

BASCOMB: Wow. So what does it entail to own a ranch at 9000 feet in the Rocky Mountains? I mean, this sounds like really hard work.

HOUSTON: Well, um, kind of the biggest thing is the weather. We have drought, we have fire, we have flood, we have blizzard. And then we have so many days that are just so spectacularly beautiful, they make your heart sing. It's a lot about protecting everything from the UV rays, which at 9000 feet are super intense. So if I don't put UV protector all over everything-- house, barn, shop, cabin -- once a year, the sun literally eats the logs away. It's about having backup plans; you know, when the power goes out, I have a good wood stove so I can keep the house warm, even if we lose power and my furnace goes out. It's about having water on hand in case the power goes out, because then the pump fails. You know, it was an amazing learning curve. Because when I came out West and bought the place, I mean, I didn't even know hot water didn't come out of the wall, you know, when you turn the tap on. So it was a lot of learning, a lot of listening to my neighbors, a lot of asking for and accepting help. When I got there, I said, my tasks fell into two categories: the things I didn't know how to do, and the things I didn't even know I didn't know how to do. But somebody would come by and say, when was the last time you protected your logs with that UV protector? And I'd be like, okay, [LAUGHS] UV protector. When was the last time you swept your chimney? So I bought brushes to sweep my chimney. It was 25 years and counting of learning.

BASCOMB: Now, your memoir is really focused on how much the ranch helped you to heal from the traumas of your childhood -- emotional abuse from your mother and sexual abuse from your father. In what ways has your ranch and nature helped you to heal, and why, do you think?

A “spirited troupe” of horses, donkeys, Icelandic sheep, Irish wolfhounds, a cat, and chickens keep Houston busy on the ranch. (Photo: Pam Houston)

HOUSTON: Well, I was born to two people who, who didn't want to be parents. And I think for some of my life, I thought that was really sad. [LAUGHS] And because I've been a writing teacher for 20 years, I have come to understand that there are many, many things that are sadder than that. But as I wrote the book, and as I talked about my relationship with the ranch and thought about it, and did the kind of deep emotional work one has to do to write a memoir, I really came to understand that my parents' lack of parenting turned me to nature, to look for sustenance and healing and succor, basically. I grew up in an alcoholic home, I grew up in a violent home, my father broke my femur when I was four years old. And I thought he would kill me, most of my life -- most of my young life. But what I did is I went and walked the railroad tracks, or I went and played horses in the woods -- which, meaning, I was the horse, [LAUGHS] running through the woods, and leaping over logs, and hitting myself with my own little crop [LAUGHS] that I broke off a tree branch. And, you know, from the very, very beginning, nature was the place I went to feel better. And when I got into the relationship with the ranch 25 years ago, my idea was to protect it, to save it, to take care of it the way it had taken care of me all my young life. And then, of course, it turned out that learning how to make that commitment and learning how to be responsible to something over a quarter of a century and learning its foibles, and its fragilities, you know, as well as its strengths and its power, gave as much to me as I gave to it. You know, in the end, yeah, I didn't have that kind of nurturing or support as a kid. But I found a way to get in relationship with something else, which at first was just the natural world around me in the places I grew up, but in my later life has become this big, long love affair with this 120 acres.

Pam Houston fell in love with the 120-acre property in 1993 and purchased it with just 5% down – all of the $21,000 advance she received for her first book. (Photo: Pam Houston)

BASCOMB: Now, what kinds of climate change impacts are you seeing on your ranch these days, if any?

HOUSTON: A lot. I'm seeing a lot of impacts. I know that probably the records would disagree with me, would say that this is an exaggeration, but it feels to me like it's about 10 degrees hotter all the time. It's, in the summertime we never used to hit 80. And now we have weeks of 86, 87. In the winter time, we would always see 35 below, that was always the mark that you'd gotten to the coldest point of the winter, you know, sometimes it would be 38 below zero, this is. Now, the coldest temperatures are like 25 below and --

BASCOMB: It's a heat wave! [LAUGHS]

HOUSTON: [LAUGHS] That might not sound like a big difference. And it might even sound like a like a good thing. But it's hard on the ecosystem. The beetles that are eating the trees in the West are related to the fact that we don't get that severe, severe cold anymore. And of course that's related to fire. Obviously, we're seeing fires all over the West, but also at the ranch, that are fires on steroids. Because the beetle kill has killed so many trees, the temperatures are hotter, we're seeing less moisture. And that all combines to make these giant fires. And we had a fire in 2013, the West Fork Fire, which burned within a half a mile of the ranch, it burned 110,000 acres and burned for weeks and weeks.

Beetle-killed forest in Colorado. Spruce bark beetles and drought have contributed to an increase in wildfires in the state in recent decades. (Photo: Hustvedt, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, you describe the fire in just painstaking detail in your book, but your ranch ultimately was spared. Why do you think that is?

HOUSTON: Well, all of our ranches were spared because we had the most amazing firefighters imaginable. At one point, the firefighters in our county outnumbered the residents by 3 to 1.

BASCOMB: Wow.

HOUSTON: We had literally thousands of firefighters saving our properties. My ranch was never evacuated, unlike many, many, many of my neighbors. And one thing I learned during that fire is that meadows really stop fires, and I was never evacuated because, I believe, the firefighters felt that I have a big meadow protecting me. And then I also have a stand of aspen at the back of my property, which is where the fire would have come from. And those aspen trees hold a lot of water in their trunks, and aspen trees will turn a fire as long as there are firefighters there to help them, you know, to help them turn it. So, I actually learned over the course of this terrifying weeks of seeing 200-foot flames shooting from the trees out my bedroom window, that I'm actually a little safer on my very ranch than some other people. Also, now that we've burned -- the forest burned in a literal horseshoe around my property. So, you know, we're probably okay now. But that sounds like a very selfish thing to say, as I hear it to my ears. I mean, the West is going to be dealing with fire as far forward as we can see, because of continuous drying, warmer temperatures and the beetle kill, which are all either directly or tangentially related to climate change.

BASCOMB: Your book's subtitle is Finding Hope in the High Country. For me and I suspect a lot of regular listeners to Living on Earth, hope may be hard to come by when each week we talked about the unfolding environmental disasters all around us. How do you personally continue to find hope?

Pam Houston writes about an incredible experience in the Arctic of stumbling upon the migration of about 800 narwhal, small whales that have a long tooth sticking out the front of their head like a unicorn horn. (Photo: Dr. Kristin Laidre, Polar Science Center, UW NOAA/OAR/OER, Wikimedia Commons)

HOUSTON: Well, I think the challenge right now, isn't about looking for any kind of hope that would fall into the naive category, I think we're in trouble and we know it and that's the reality. But I also think that probably being an adult means being able to hold the hope and hold the sadness and the sorrow about this climate catastrophe together. I was up in the eastern Canadian Arctic and two days in a row just showed me this so clearly. The first day, we completely against all odds, once in 10 lifetimes experience, we got into the annual narwhal migration in our boat. So, we're in a boat and we're running with 800 narwhals you know, which most people never get to see in their lifetime.

BASCOMB: Wow, that must have been amazing. I mean, narwhal, for people that are not familiar, they're a whale with a giant spike off their head, sort of like a unicorn or something, that they use to poke through the ice. Is that right?

HOUSTON: That's right. It's actually a tooth. But yes, it looks like a spike. And it's a tooth that grows forward out of their mouth and out into the front of them, like a unicorn horn. They believe they're the original unicorn myth. And it was the most staggeringly amazing thing, you know, in a life of amazing outdoor experiences, it might be number one for me. But at the same time watching those narwhals was the knowledge that probably even more than the polar bear the narwhal are threatened by the melting sea ice because they need the sea ice to hunt. And then the very next day a little further down the coast of Baffin Island, we saw this blue thing out in the distance. And you know, we're like, what is that? Is that an island? Where are we? And it turned out to be a five mile by five-mile chunk of ice. And it was staggeringly beautiful, it was made of crystal blue glass, and it had giant rivers pouring off of it in these sort of porcelain white blue pour-overs. And, you know, it was bigger than we could see around from our boat, and just this gleaming thing in the sun. And of course, it was the piece of the Greenland ice shelf that had fallen off in 2012, and it was still floating out there. So, you know, never was there a more beautiful object, and never was there more evidence of the trouble we're in. There it was, you know, all together. And, and I see, I see versions of that every single day. And, you know, I think one of our troubles right now in this country, is it like, is it this or this? Are they with us or against us? Is it us or them, you know. And it seems like, you know, "and" is the operative conjunction. Like, yeah, it's, it's magnificent, the earth is magnificent -- and it's in dire trouble because of us. And that's a hard truth. But I don't think we can lose either of those. I don't think we can lose the joy at the wild things we still get to experience, so that we might fight for its life.

Pam Houston and her horse, Roany. (Photo: Mike Blakeman)

BASCOMB: Pam Houston is author of Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country. Pam, thanks for taking this time with me.

HOUSTON: Oh, you're welcome. It was my pleasure.

Links

“Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country”

Outside Online | “Pam Houston’s ‘Deep Creek’ Is (Of Course) Fantastic”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth