Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Air Date: Week of June 7, 2019

Walden Pond in Corcord, MA was a source of inspiration for nature writers Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. (Photo: Flickr, Mike Mahaffie CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In the mid-nineteenth century, the nature writers and transcendentalists Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson shared a rich and fulfilling friendship, but it wasn’t always smooth sailing. A new book, "Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson", traces this complex relationship through the two writers’ journals and letters. Author Jeffrey S. Cramer is the curator of collections at the Walden Woods Project in Concord, Massachusetts, and sat down with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss how the two helped each other grow as writers.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Henry David Thoreau might never have built his tiny cabin at Walden Pond or written his classic book "Walden" if it weren’t for Ralph Waldo Emerson, his mentor, friend, and fellow nature writer. While a student at Harvard, young Henry came across Mr. Emerson’s essay on nature.

MAN READING FROM “NATURE”: In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, no disgrace, no calamity (leaving me my eyes), which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground, my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, all mean egotism vanishes.

CURWOOD: While Ralph Waldo Emerson is little read in the 21st century, his thoughts are echoed in Henry David Thoreau’s "Walden", which is widely read by high school students today.

MAN READING FROM "WALDEN": I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

CURWOOD: Jeffrey Cramer is the curator of collections at The Walden Woods Project, a non-profit dedicated to protecting the woods surrounding Walden Pond where Mr. Thoreau lived deliberately. And Jeffrey Cramer has a new book called "Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson". He spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Living on Earth producer and reporter Jenni Doering sat down with "Solid Seasons" author Jeffrey S. Cramer. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

DOERING: Why did you decide to write a book about the friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson?

CRAMER: I've never quite been happy with the way the friendship has been portrayed in biographies. So, I felt that it was time to really bring out the personalities of both men, to make them more human rather than iconic, and to tell their story.

DOERING: So, why did you call your book “Solid Seasons”?

CRAMER: So, I did that because there was a phrase that Thoreau used in "Walden" where he said, “there was one other with whom I had solid seasons, long to be remembered at his house in the village.” And he's talking about Emerson and he's talking a little bit about a rift they had in their relationship at one point. But, what surprised me was, I found that same phrase in a letter that Emerson had written to Thoreau from New York, in which he said, “I have had what Quakers call a solid season, once or twice.” And, therefore that phrase, “solid seasons”, was something that Thoreau picked up from Emerson. So, I just love that they both use that one phrase, to talk about those kinds of very strong and powerful personal friendships. And, what I take it to mean, and I think it's certainly how Emerson and Thoreau both used it, was that the solidity of the friendship, the strength, the power of that, and that's something that's so rare. So to have that season of friendship, whether it's short or long with that kind of powerful solidity was just an amazing thing.

DOERING: When did they first meet?

CRAMER: They met sometime after Thoreau graduated from Harvard. There are a few different stories. So they may have met shortly before that shortly after, but they met primarily because people noticed connections between Thoreau's early writings and Emerson's, and they brought them to Emerson's attention. And he took Thoreau into their household, ostensibly as a handyman, but also to help with editing Emerson's works and to learn more about the whole writing process.

DOERING: Yeah, I mean, you write in your book how people were talking about Thoreau as imitating Emerson. To what extent do you think that was true, or just an impression?

CRAMER: I think it might have been true, but not conscious. So I think definitely there were things in Thoreau's mannerisms that may have been unconsciously trying to imitate Emerson, whom he admired. I don't think it was something he set out to do. I don't think he tried to be Emerson in his writings. I don't think he meant to start looking like Emerson as people claimed he did, or talking like Emerson, but I think it was just something that happened.

"Solid Seasons" provides new insight to the friendship between Emerson and Thoreau. (Photo: Courtesy of Counterpoint Press)

DOERING: I mean, their relationship wasn't uncomplicated, right? And, I think Thoreau had a lot more angst maybe than Emerson about it, from what you write. So, what was the issue there? What came between them? And why was there such a concern about, is this really the friendship that we want?

CRAMER: Yeah. So, both men I would say had ideals about what a friend should be. Thoreau seem to have put all of his faith in one person at a time. So, the friend, the ideal friend he wanted, particularly after his brother John had died, seemed to be Emerson. And so Emerson disappointed him in various ways along the times of their friendship, particularly in relation to his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, that Thoreau felt that Emerson should have promoted more. Emerson, however, didn't try to find the one ideal friend in one person, he found different aspects of that ideal friendship in many people. So Thoreau was just one of the many friends that Emerson had; although, certainly later in life, he kept referring to Thoreau as his best friend. So it became something greater than I think Emerson realized at the time when both men were alive.

DOERING: That actually reminds me about the fact that reading your book, it sounds like Emerson, just, his respect for Thoreau, after Thoreau had died, just kept growing until the end of his life or you know, near the end of Emerson's life. That he recognized what a great soul the world had lost, a great writer. Why do you think that that sort of transformation happened for him? Or can you characterize that?

CRAMER: Well, I think one of the things is Thoreau could be annoying. He could be a difficult friend. As one friend said, “I love Henry, but I do not like him.” So I think sometimes when you would have Henry in the room with you, it would, might be difficult to actually hear some of the things he's saying. I think when Thoreau died, and Emerson started reading his journals very carefully, and all of his writings again and again and thinking about him in relation to writing his eulogy, but other things – I think he realized what Thoreau offered the world. And at that point, the personality, the things that could be annoying in the friendship, were gone. And all he’s left with is the brilliance of Thoreau's words and writing, as well as the love that still remains in his heart for his friend that he lost. So I think at that point, he could really start thinking about Thoreau in a different way. And, as you mentioned, over the next 14, 15 years of Emerson's life, he really spent all that time talking about Thoreau, and people would come to visit Emerson in Concord, and he would say, you know, “let's not talk about me, let me tell you about Thoreau.” And it was just so interesting to see that. And he realized also that a lot of his own ideas, which had been represented in Thoreau's writings, or were very similar, Thoreau took them to a greater degree, and Thoreau tried to live that life. And Emerson was more on an intellectual level. He wrote about things; I don't think he felt them as deeply as Thoreau did. And I think that's one of the reasons we connect with Thoreau now and not Emerson is that we feel that there is a person who is speaking directly to us. And it's why so many Thoreau scholars, when they write about Henry, or talk about – I just did it – why we start calling him “Henry” and not Thoreau, but nobody ever calls Emerson “Waldo”.

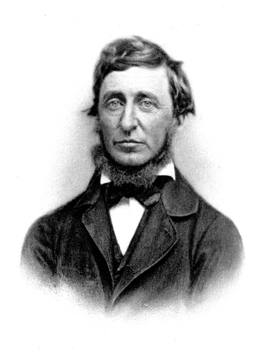

Henry David Thoreau is widely known for his works "Walden" and "Civil Disobedience", as well as many others. (Photo: Courtesy of the Walden Woods Project)

DOERING: So, you mentioned that after Thoreau died, Emerson started reading his journals. But we now have both of their journals. What do you think they would have thought about their private thoughts being read by all these millions of people now?

CRAMER: Well, the journals in those days were not quite the same as a diary today. So they weren't as private, they did get shared, you might actually loan your journal to a friend. And so it wasn't quite the same. But there were certainly remarks in both men's journals about the other person that may have been difficult for Emerson to read, certainly later on, as he's reading what Thoreau had to write about him. But overall, I don't think they wrote things knowing that the other person would read them and as a form of criticism that they should read, but I think they used it as a place to put down their thoughts and if the other person happened to read them at some point in time, so be it.

DOERING: What kinds of surprises did you come across in writing this book?

Ralph Waldo Emerson was known to be a mentor to Thoreau, but he was greatly influenced by his mentee as well. (Photo: Courtesy of the Walden Woods Project)

CRAMER: The surprises that I came across was, for me, how much Thoreau influenced Emerson. I mean, it's, it's obvious in every biography that Emerson influenced Thoreau. What I found was, and this was surprising, was how much they worked off of each other and shared ideas and grew from that exchange. One of the other things was, as I put the book together, I would put all their writings about each other in chronological order. So I could sort of get a better picture, which didn't quite exist when you read each man's work separately. And what I found was that at certain points when they're out together on the pond, or in the woods, having a conversation, when they go home, and they're both writing in their journals about the same experience, how do they write about it? And I remember one particular time where Emerson finished his first book of essays, which contains the essay “Friendship,” and they went off to Walden Woods for a picnic. And they’re both having a nice time and they go home, and Emerson's writing, you know, it's a lovely day, the sun on the water is beautiful, and our friends are nice and blah, blah, blah. And Thoreau goes home and he writes, Friendship is horrible! People suck! And he goes home and he's ranting about what is not right about his friendship with Emerson; I'm thinking, you two just spent like an hour or two in the woods, having the same conversation with each other, seeing the same scenery, and you both go home and write completely different things. Those kinds of things don't show up unless you start merging all of their writings together, which is what I had to do to create this book.

DOERING: I mean, and they seem to have a different relationship with nature, although they were both writing about nature a lot and talking about it. But, Thoreau was the one who would go out and actually be more part of nature. I think Emerson was a little more cerebral about that.

CRAMER: Definitely. But, Emerson did love being out in nature. I mean, he would go for walks, he would go boating on the river with Thoreau, or on the pond. He spent a lot of time outside, but it wasn't quite to the level that Thoreau did it. I mean, Thoreau needed desperately to be outside three, four hours a day. It didn't matter what the weather was, that was part of his life, that was part of his work, that was part of his being. For Emerson, it wasn't the same, he enjoyed going out into nature and seeing nature, he enjoyed being out on the pond, he enjoyed going for long walks in the woods. But it wasn't that kind of same integral part of his life.

DOERING: They were both very independent thinkers, and you know had a, a strong moral framework. What do you think that they would think about sort of the political system we have today – and climate change, this huge moral dilemma that we're, we're facing?

Jeffrey S. Cramer is not only the author of "Solid Seasons", but also the Curator of Collections at the Walden Woods Project’s Thoreau Institute Library. (Photo: Courtesy of Tom Hersey)

CRAMER: Both of them were very involved in social reform and political things that were going on in the world in their day. But they also stayed out of it for a little bit. I mean, Emerson was often reluctantly drawn into various frays; once he was there, he was in it full heart. Thoreau, had no love for the political system, the political world. So he again, he stayed out of it as much as possible. For Thoreau, the idea of changing the world was through self-reformation. That we change ourselves, change how we live, we change what we're doing that affects other people or the world. That is how we make change. So, for him, if we're looking at global warming and climate change, what are we doing as individuals that are causing this dilemma, this problem, and he would change things in his life so that he's no longer contributing to it. And, so, he's throwing the responsibility for what is happening directly back to the individual. We cannot rely on other people to solve our problems. We have to solve them ourselves. There are a lot of people who say that's not going to work anymore. I mean, Bill McKibben's clearly said, you know, driving your Prius isn't going to save the world anymore. Still, if we all drove Priuses, it would. If we all did this or that it would change things. So Thoreau and Emerson would take that sense of we as individuals have to reform our lives. And, that's the way to change the world.

CURWOOD: That’s Jeffrey Cramer, author of "Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson", speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Links

"Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth