Resilient Corals Get a Helping Hand

Air Date: Week of June 28, 2019

A diver with Raising Coral Costa Rica tends to a floating garden of Pocillopora corals. (Photo: © David Garcia / Ecodiverscr.com)

More than half the world’s coral reefs have died in the last few decades and scientists predict that as many as 90 percent could die off this century as the ocean chemistry changes and temperatures rise. But some coral populations are actually thriving in warmer waters, and scientists are working to speed up natural selection by propagating these resilient corals. Joanie Kleypas, founder of the nonprofit Raising Coral Costa Rica, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about her work.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The world’s coral reefs are in dire straits. More than 50 percent of corals around the world have died in the last few decades and scientists predict that we’re well on our way to a 90 percent die off this century. Warmer ocean temperatures, ocean acidification, and poor water quality combine to make a toxic environment for most corals. But some corals are actually thriving despite their challenges. And scientists like Joanie Kleypas are hoping they will be able to propagate these resilient corals to give struggling reefs a leg up. Joanie is a Senior Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and founder of the nonprofit Raising Coral Costa Rica. She says their results so far have been encouraging.

KLEYPAS: It's remarkable, really. I mean, you take these small samples of coral, and you put them in the nursery. And, you know, the point I like to make is they really want to grow. Some of these corals look bad when you collect them, and then you put them in this really nice environment and they grow like crazy. It's really a fulfilling experience to see that. In fact, one of the species we're working with, this is off of the Pacific side of Costa Rica, which is really a low diversity area, but the reefs are still really important there. We could not find a species of coral that was very important, it was a branching species; it had been wiped out mainly by sedimentation. But we eventually did find a few colonies, about 10 so far. And we take samples of those, and we put them in the nursery. And they, we just started with little, you know, fingertip-size pieces that were white and bleached. And now we have hundreds of colonies just in the nursery, and we're out planting them back on the reef. And it looks like we might be able to bring that species back. But the entire time we're thinking, well, these corals have all only been found in deeper, cooler waters, we're not sure if they'll survive the next bleaching event. And we recently found a colony in a very shallow, warm water part of the region where we're working. So we know that species survived the last bleaching event. And it would be very good stock, and increase our genetic diversity, to culture that thing, so we, we have samples of that in our nursery right now. And they're growing really well.

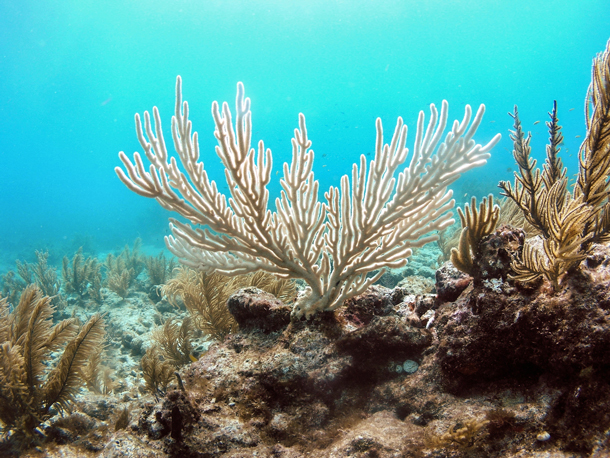

Ocean warming and acidification are causing corals to bleach, meaning that they lose their symbiotic algae. If stressed for too long, they can die altogether. (Photo: Kelsey Roberts, U.S. Geological Survey)

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. So you are taking samples from places that are doing well right now and growing those out, and then planting them out again?

KLEYPAS: Exactly, we're just speeding up what they would do naturally, by probably about five times or more. When you knock a population of corals down to so few, then when they do reproduce and release their eggs and sperm in the water column, the probability of an egg and a sperm finding each other is really low. But if we can go into some of these areas and plant thousands of these corals of different genotypes, when they spawn, then they will find each other. So, that sort of brings them past this threshold of having such low numbers to a point where they can become self-sustaining again.

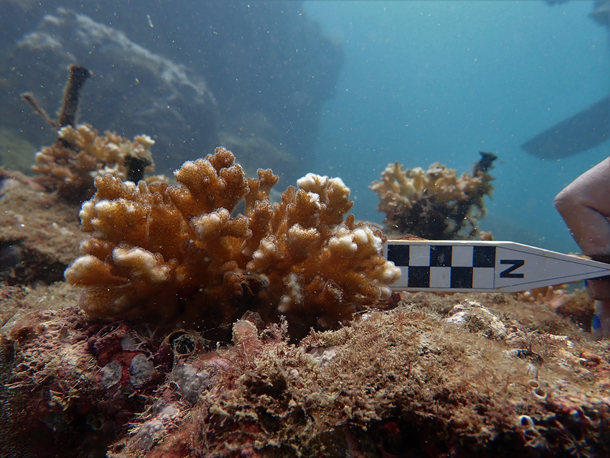

Pavona corals transplanted by Raising Coral Costa Rica. Pavona corals are nicknamed cactus, potato chip, and lettuce corals. (Photo: Raising Coral Costa Rica)

BASCOMB: Right. And are you just working in Costa Rica, or do you have plans to collect corals in other parts of the oceans?

KLEYPAS: So far, we're really concentrating on the Pacific side of Costa Rica. There is a lot of work being done all over the Atlantic, people are doing this a lot with a couple of the endangered species, in particular, of the staghorn and elkhorn corals. These are big, major species that used to be the foundation of the reefs there. And they've had a lot of success of bringing these corals back and increasing the genetic diversity that they have in their nurseries, and in starting to work with the other species as well, so there's been a lot of success in the Caribbean. On the Pacific side of Costa Rica, there's very few people looking at this. And we like working there because even though there's just a few species, they're really tough there. They're tough because they have to be; it's kind of a harsh environment. The temperatures, you know, can be quite extreme, the pH of the water is pretty low, and yet they thrive. And if you're going to propagate species for the future, you need to find those tough corals.

BASCOMB: So can they only live in that one environment? Or could there be a scenario where you take those corals in the Pacific of Costa Rica, and plant them in the South Pacific, you know, someplace else entirely, where maybe you're not finding those tough, resilient corals? Or would they not survive because they just don't belong there?

Pocillopora corals like these transplants are also known as cauliflower corals. (Photo: Raising Coral Costa Rica)

KLEYPAS: This is one of the other interventions that scientists are talking about: can we move corals around? It's one of the riskier ones. The problem is when you move corals around you, you move around not just the coral, you move around the bacteria that it has on it, you move around all these other species that live on the coral. So there's a risk of introducing invasive species or diseases, so you have to be really careful about moving them around. And certainly, we don't recommend anyone put their own corals from their aquarium in the ocean, just for that reason, we want to avoid any kind of invasive species. But there are also ways to get around that. So they're starting to freeze eggs and sperm. And recently, there was a project where they were able to fertilize eggs of a coral with sperm that were transported from the other side of the world and produce viable offspring. So, that eliminated the bringing of invasive species with that, if you're just bringing the sperm, that eliminates that probability. So there's some really cool and innovative ways that people are figuring out how to deal with these risks.

BASCOMB: To what extent are people talking about genetically modifying corals at this point, in another effort to save them?

KLEYPAS: Well, when you say genetic modification, you can think of it two ways. One is, is sort of the natural way, by like, crossbreeding corals. Again, it's the same sort of thing we do with crops and so forth, you just breed a better coral. There are some people thinking about creating better corals through genetic modifications, through some of these new genetic techniques. And they're thinking about doing that not just with the coral animal, but with the symbiotic algae that lives inside the coral and makes it such an efficient organism. That scares a lot of people. I think, you know, we need to be careful on that, I don't think we're going to be in danger of creating Frankenstein corals. But most of the genetic studies that are going on now are really designed to understand what's going on inside the coral when it is adapting to a temperature change. How do we understand what's happening to that coral by looking at its genetics, rather than trying to change the coral with the genetics. But it is something in the toolbox that needs to be evaluated along with the risk before we use that kind of technique.

BASCOMB: How have corals responded to previous fluctuations in global temperatures? You know, the Ice Age and things like that. I mean, is this the first mass dying of corals that we've seen, you know, in their history on earth?

Joanie Kleypas is a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder CO, and studies how climate change and ocean acidification impact coral reefs. She has conducted research on coral reefs for more than 30 years, and now concentrates on finding solutions to coral reef decline. (Photo: Carlye Calvin, © UCAR)

KLEYPAS: Well, corals -- you know, the stony corals, those evolved in the Triassic, that was 240 million years ago. They're still around, and they've had their ups and downs through geologic history. They've apparently, you know, almost completely disappeared from the geologic record. There's no sign of them ever being preserved. But they always seem to come back. The last time they had a big wipeout of the corals was when the dinosaurs went extinct. And then again, 10 million years after that, in a period of time when the Earth's atmospheric carbon dioxide also went up really quickly. And the reefs that had finally started growing again after the Cretaceous event, they ended up really diminishing a lot during this high CO2, high ocean acidification event 55 million years ago. So they've gone through all of these cycles, up and down, up and down. But most of those changes have been a lot slower than what we're seeing today. That's the problem. We know corals can adapt. They have a huge capacity for adaptation. But right now, it's just too fast. It's faster than they can do it themselves. We are having to become part of that ecosystem to help speed up the rate at which they can adapt.

BASCOMB: Joanie Kleypas is a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and founder of the nonprofit Raising Coral Costa Rica. Joanie, thank you so much for sharing your story with me.

KLEYPAS: Bobby, thank you. It's been a pleasure and a privilege. Thanks.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth