Andrew Yang’s Climate Plan

Air Date: Week of September 13, 2019

Andrew Yang’s signature proposal is a “Freedom Dividend” of $1000 a month for every US citizen over the age of 18. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

Democratic Presidential candidate Andrew Yang is calling for a universal basic income, which he calls a Freedom Dividend. He wants the federal government to send a thousand dollars each month to every US citizen over the age of 18. The 44-year old entrepreneur sat down with Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how the plan relates to his five-pronged proposal to address the climate emergency, which envisions the U.S. economy achieving net-zero emissions by 2049.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Nearly all the Democratic presidential candidates would beat out President Trump in New Hampshire, according to a recent Emerson College poll. In a head to head matchup, 44-year-old entrepreneur Andrew Yang would beat President Trump by 8 points. Only Joe Biden would have a larger margin according to the poll. Mr. Yang is perhaps most well known for his proposal of a universal basic income, which he calls a “Freedom Dividend.” That’s a thousand dollars each month to every American citizen over the age of 18. I asked him to relate that plan with his 5-pronged proposal to address the climate emergency, which envisions the US economy achieving net-zero emissions by 2049. I sat down with Mr. Yang at the New Hampshire Public Radio studios in Concord. Andrew Yang, welcome to Living on Earth!

YANG: Thanks for having me. It's a pleasure to be here.

BASCOMB: So Democratic voters rank climate change as a top concern in the 2020 campaign. If you win the Democratic nomination and are elected President, what policies would you enact to address climate change?

YANG: So the first phase is to try and move towards a renewable economy ourselves as a source of energy. One big component of this is to me a carbon fee and dividend that helps internalize the cost of carbon emissions on to producers and companies. Because right now, when they pollute, there's no accounting for all of the harm that's being done to us all, collectively. The second pillar is moving towards a sustainable world. And this is the difficult truth: that the United States is only 15% of global emissions. So even if we were to curb our own emissions dramatically, climate would continue to warm. So the question is, how can we move the other 85% of global emissions in the right direction? And what's happening right now is that China is going to Africa and saying, "Hey, I've got a power plant for you. It burns coal." And then Africa says, "Great!", because their interest is just trying to get cheap sources of energy by any means necessary. So to curb that set of emissions, we're going to have to go to developing countries and say, "Look, don't use the coal power plant, use these wind turbines or solar panels, and we're going to make them cost effective for you." The third thing is to move ourselves and our people to higher ground. So my flagship proposal is putting $1,000 a month into every American adult's hands, which will make us all more able to adjust and adapt. But we need to have public resources in place so that communities that are experiencing climate change can realistically address and mitigate those effects. And so the fourth part is to try and reverse some of the damage that's being done. So that includes reforestation, that includes seeding the oceans, that includes investing in research to try and find more renewable forms of energy, but also ways that we can actually undo some of the damage that we're doing. And then the last part is the shortest, but maybe the most important: we should have a constitutional amendment that says it is the government's responsibility to safeguard, protect and preserve the environment for generations to come.

BASCOMB: Now, perhaps the policy proposal that you're most well known for is the Freedom Dividend. And that's a universal basic income that would give every American citizen over 18 years old $1,000 per month. But generally speaking, more money for consumers means more consumption. And while that may be good for the economy, it's not usually good for the environment. How do you respond to that?

YANG: A couple things. One impediment to making progress on climate change is that 78% of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck, and almost half can't afford an unexpected $400 bill. And if you come to them and say "we need to fight climate change", a lot of them look up at you and say, "I can't pay my bills today. I'm not worried about 10 years from now". And so if you get the boot off their throats with $1,000 a month they look up, they feel like their future's assured, their children's future's assured, then all of a sudden, they'll say, "Wow, yeah, we really do need to make progress on climate change". We can actually speed up addressing climate change by lifting this mindset of scarcity that right now has swept our communities. In many cases, there are many people that, I think, if you had $1,000 a month, might actually adopt a more minimalist style of life. You can imagine four people getting together and saying, "hey, among the four of us, that's $4,000 a month. Why don't we just get a small home, and then, you know, live there, and then you'll work on your screenplay, like, you know, like, I'll commute and work as I'm doing now, like, someone else will be a caregiver." There is a world where the carbon footprint of a group of people might actually not go up if you have these resources that are, frankly, more flexible and dynamic. You know, they put you in a position to make more human choices. And the example I use in my own family is that my wife is at home with our two young boys right now, one of whom is autistic. And her work right now is considered to have zero value in the economy and GDP and the marketplace. But we know it's the most important work that anyone does. The goal would be to expand our notions of what work is. And I think a lot of the work that we would like to be doing will actually be very positive for the environment.

BASCOMB: Part of the universal basic income is to supplement the incomes of people whose jobs are going away because of automation. But also there are, I mean, industries like coal miners, you know, which are middle class people in these swing states like Ohio; to what degree do you think that this Freedom Dividend would benefit those types of workers?

YANG: Well, it would be a tremendous step forward for many Americans, because $1,000 a month goes very far in a lot of the country. And the truth is that when some of these jobs are being lost, we're selling that we're going to retrain American workers for the new jobs. But the numbers show that almost half of the manufacturing workers who lost their jobs never worked again. And that was with government retraining. Government retraining is largely ineffective in many environments. Independent studies have shown its effectiveness rate to be between zero and 15% in some of these environments. So we have to be more direct and honest about providing more American workers a path forward in a way that they'll actually be able to make use of.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I mean, we hear "Oh, we'll just retrain coal miners to make solar panels instead." But it's not that easy.

YANG: It's really not that easy. We're not infinitely adaptable. We're not widgets, like, imagining that middle-aged men and women are just going to go up and be like, "All right, now I'm a this; now I'm a that", like, that's just not the way humanity works. We have to be more honest. The biggest mistake we're making is that we're equating economic value and human value. And we're saying that if your job is no longer relevant, then you're worthless, and we have to find something new for you to do or you will continue to be worthless. And that's a very erroneous approach to these problems. We have to reverse it and say, Look, we're all human beings, we have intrinsic value. What good is record high GDP if the economy is not working for us? Instead of treating us all as economic inputs into this giant capital efficiency machine, we should be asking ourselves, how is this economy designed to optimize our well being? And that includes sustainability and a climate that is healthy and strong for us and our kids.

BASCOMB: You've also proposed some geoengineering techniques, technologies. Can you talk a bit about that -- what, and why?

YANG: So geoengineering is a big scary word. It sounds awfully daunting. But even if you do something like planting lots of trees, that's technically geoengineering. And I think everyone would be excited about that, because trees capture carbon and bring it out of the atmosphere. So what else could geoengineering look like? It could look like re-seeding oceans; it could look like trying to make clouds more reflective, so that some more of the sunlight doesn't end up heating up the oceans or land. If you look around the world, you have several island countries that are literally getting lost to the ocean and are submerging. Now, these countries are not in a position where they could legitimately geoengineer, because they don't have the resources. But if you were a country that was a world power, that did feel like it was in your interest to do so, you might take matters into your own hands. And I'm thinking of China, specifically, because China has massive climate change related problems. And they're not very consultative. You can imagine them spraying sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere above their own country and just shrugging, and not telling anyone else they were doing it. So the question is, how do we avoid that scenario from unfolding 25 years from now? And to me, the answer is to exert American leadership and say, Look, let's get together the world's researchers and scientists who are looking at different geoengineering measures, and see what people are finding out, to see what we're learning, see what's on the table, and try and achieve some kind of global consensus and structure rather than having individual actors go off on their own.

BASCOMB: But all of these things that we've been talking about cost money. Your plan sounds expensive; where do you think the money for it would come from?

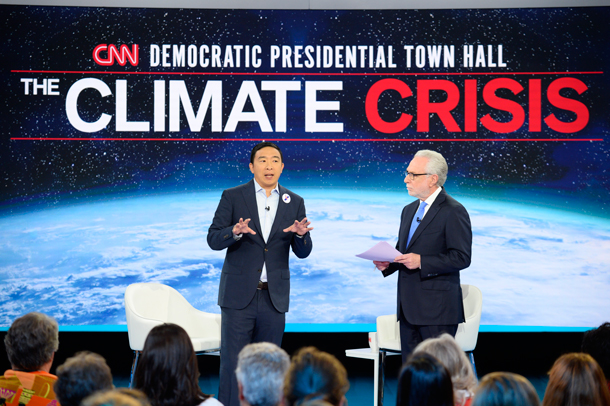

Andrew Yang laid out his plan to address climate change at the 7-hour CNN Climate Crisis Town Hall on September 4, 2019. (Photo: CNN)

YANG: Well, the first big thing, and I think most people listening to this would agree, is that the real expense is going to come if we do nothing. We're talking about trillions and trillions of dollars in lost commerce and devastation, but also human life. The other thing is that over our history, we subsidized fossil fuel companies to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars, and now they act like anything we do in this other direction is going to, quote unquote, hurt the economy. It's ridiculous. We have to do away with this supposed tug of war between doing right by the environment, and growing the economy and creating jobs. We have to redefine the way we see economic progress. We have to start accounting for the fact that record high GDPs are meaningless if your GDP goes up every time there's a hurricane, because, you know, I mean, like a hurricane actually means you have to rebuild a bunch of stuff. So it's like oh, GDP went up, for like the worst possible reason. So we have to redefine our economic measurements to actually correspond to true progress. And one of my goals as president would be to change GDP to be a more complete measurement, that included things like children's health and wellbeing, mental health and freedom from substance abuse, clean air and clean water -- things that would actually correspond, in many cases, to a sustainable planet. And if this sounds difficult to you, keep in mind that we made up GDP almost 100 years ago. And even the inventor of GDP at the time said this is a terrible measurement for national wellbeing and we should never use it as that. So it's 100 years later, we need a new measurement that includes our environmental sustainability. And that way we can do away with this destructive tug of war that we either choose the economy or a sustainable future.

BASCOMB: Now I've read that your favorite president is Theodore Roosevelt, who was an outdoor enthusiast, and a huge conservationist. I mean, he set aside more than 200 million acres of public land. But why was he your favorite president?

YANG: Well, that was part of it. I mean, we all owe him some of our national parks and some of the greatest national treasures. But I like the fact that Teddy was very solutions oriented and bipartisan, and wasn't afraid to go against the grain in terms of powerful interests of his time. He was a trust buster. And I think that there are some parallels to what's needed now. His "Man in the Arena" speech spoke to me when I was young and first read it. There's also this thing, and this is going to be a little bit, you know, sound like a movie character or something. But there was one time he got shot during a speech and then finished the speech. Like -- [LAUGHS] and so you know, like, some of these impressions, to me, made him seem like the archetype of the kind of President we would need in a time of trouble.

BASCOMB: Mmm, sort of larger than life; I mean, if you can finish a speech with a bullet in your body! ... [LAUGHS]

YANG: Yeah, he got shot in the shoulder, and then was like, "I'm gonna finish this." Afterwards, he got taken for treatment. No promises I would do the same, I'm sure if I got shot, I'd be like "hospital now, please".

BASCOMB: Yeah, yeah [LAUGHS], anybody would. On your website, you discuss the need to protect American public lands. I wonder if you'd like to share a couple of your favorite places to go -- you know, public lands, national parks or anything like that?

YANG: So I went to Yosemite with my brother for his bachelor party hike. So as you can tell, we're pretty boring, like, if that's the bachelor party celebration --

BASCOMB: Sounds good to me! [LAUGHS]

YANG: [LAUGHS] Yeah, sounds good to me, I mean it was great! And it was so breathtaking; you almost couldn't believe what you were seeing. It was something that you have to experience to, to understand. So I think Yosemite as a national treasure is amazing. And then in upstate New York, there's a set of mountains there called the Shawangunks, the Gunks; I've done some climbing and hiking there. And in both of those environments, you almost can't believe it, it's like, it's like it was designed for you to hike. [LAUGHS] How else to put it? Like, it's almost too good to be true. It's like, it's almost as if someone deliberately tried to make this terrain ideal for a hike, this is what they would do.

BASCOMB: Andrew Yang is an entrepreneur and Democratic candidate for the 2020 presidential election. Andrew Yang, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

YANG: Thank you for having me. It's been a joy sitting down with you.

Links

Andrew Yang campaign’s climate change plan

InsideClimate News | “Andrew Yang on Climate Change: Where the Candidate Stands”

Living on Earth’s coverage of CNN’s Climate Crisis Town Hall

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth