Success of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

Air Date: Week of October 4, 2019

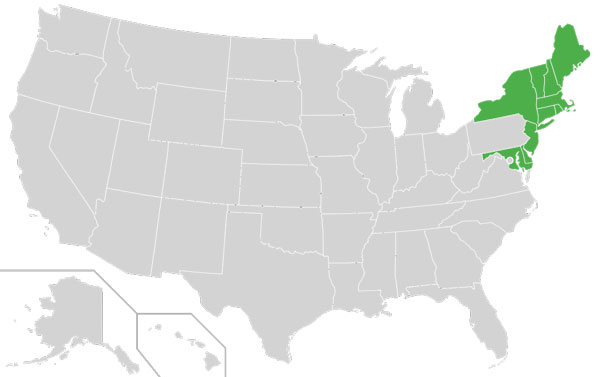

Including Pennsylvania, RGGI is comprised of 10 members states in the Northeast United States. (Photo: MarginalCost, Wikimedia Commons, CC)

In 2005, seven Northeast states teamed up to create a market-based carbon reduction plan best known by the acronym RGGI, and since then three more have joined . David Cash, from the University of Massachusetts Boston helped create the plan. He tells host, Steve Curwood, about a new study that finds participating states have dramatically reduced their emissions while at the same time lowering electricity rates for consumers. After the recording of this segment, Governor Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania began taking steps to add the Keystone State to the RGGI plan.

Transcript

CURWOOD: The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative called RGGI, is one of the unsung heroes fighting climate change in the United States. It’s a market-based collaboration among ten states in the Northeast that caps and gradually reduces carbon emissions from electric power plants. Revenue from RGGI is invested in clean energy projects, energy efficiency programs, and green startups. A new report by the Acadia Center tallies up the CO2 reductions, cost savings, and health benefits of the program and found that power plant emissions in RGGI states have fallen by almost half in ten years and that’s 90 percent more than the rest of the country all while making electricity cheaper. David Cash is a former energy and environment commissioner for Massachusetts who helped develop RGGI, and he now leads the McCormack Graduate School at UMass Boston. David Cash, welcome to Living on Earth!

CASH: It's great to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So exactly where did the idea for-for RGGI come from? Why the 10 northeast states?

CASH: In the early 2000s, it was becoming more and more apparent that climate change was a significant issue that would have health impacts and ecosystem impacts and damage our coasts. All of the things that we actually see happening now. Increase of wildfires, more hurricanes, and more severe hurricanes, all of those kinds of things were predicted then. And it was also seen more and more, that there were significant economic opportunities that might come with addressing climate change if one did it wisely. There would be opportunities for reduction of energy costs, there would be opportunities for innovation and job growth in the clean energy sector. And at the time, there had been cap and trade programs, for SO2. It was very successful at combating acid rain, with the cost of compliance, much less than anyone had predicted. And the innovation of new technologies, much better than anyone had predicted. We thought this would be a really good opportunity to address this problem in a market, you know, the Northeast is a pretty good market, it's large, we are all on combined electric system. So it would be relatively easy to regulate. And the Northeast has been a mover in environmental issues, historically.

CURWOOD: Now, SO2, sulfur dioxide, you point to that as an example of a cap and trade program that worked really well. Just what exactly was that cap and trade program and how those work anyway?

CASH: Here's a critical parts of cap and trade. The government sets a limit on what the entire industry can emit. Now, I don't remember the exact tons in SO2. I'm gonna say 100 and thats very, very low. But let's say the whole industry, the whole electrical industry can only emit 100 tons. And let's say they're emitting 120 right now, right. So in sometime future, they have to be under that cap. So those power plants that can be really efficient and produce more electricity without emitting so much, they're going to have allowances, they can sell to some of those plants that aren't as efficient. And in the SO2 program, all of those power plants were given their allowances, they call them grandfathered. So if you emitted eight tons last year, or whatever the year was, you know, they have a baseline year, you got your eight tons, and then you could trade those. Now, if you think about it, that means you're given a lot of value to these companies, right.

CURWOOD: Mhm.

CASH: And at that time, with this being the first ever of these kinds of complicated programs, politically or otherwise, it was smart to give those out. Even though the government and the public lost out on the value of those. Okay. By the time we came to doing RGGI, there was a lot of debate within the RGGI states, do we require an auction? Do we require a certain percentage? They're being allowed to pollute. They're being allowed to dirty our air. Now to limits that we think will not damage us too much or the planet that much. But that's quite a privilege, and they should pay for it. And, so, that's how we structured the RGGI program was that they had to buy those allowances. So that was one way states got that money. And in Massachusetts, we plowed it right into energy efficiency. We made it easy for you to get energy efficient stoves, energy efficient furnaces. To winterize your house, to get energy efficient light bulbs. All of these things that might cost a little bit more, we made it easy for you to do that. We plowed that money right back into it. So that's one way. The other way is, remember, the power plants had to buy those allowances. Would wind plants have to buy those allowances? No.

CURWOOD: No.

CASH: No, of course not. Because they're not admitting anything. They don't need an allowance, right? You use the allowance, at the end of the compliance to say I admitted 10 ton here are my 10 allowances that shows, that keeps everybody in compliance. Wind doesn't have to do that. So if you're a wind developer, there's a whole expense you don't have to worry about. So you can compete. Those are the two basic ways that the market really works well in these kind of programs.

CURWOOD: And then what about the factor that if you are taking this money and you're providing it to electricity consumers to buy more efficient. Everything from light bulbs to the furnaces and such, that would lower the demand for energy. And if you lower demand, you tend to lower prices?

CASH: Exactly. That's the third way that I didn't talk about. That you're lowering demand throughout all of this, which means, as you say, basic economics 101 has less demand and the price should go down. So the price goes down. So our models showed that even for customers who would not get new light bulbs and all that kind of stuff, their energy bills would generally be going down.

CURWOOD: Of Course one of the big obstacles for this was, in fact, how the state of Massachusetts was towards the end of these negotiations. Tell me that story?

CASH: Sure. So, Massachusetts had been a very active player from the beginning, shortly after Governor Pataki republican governor of New York had invited the Northeast governors to participate. And I mean, we had thrown lots of resources at this from the highest levels. Lots of staff hours went into this, and a lot of investment went into this. And during the negotiations, this give and take between governors, between states, we worked hard to get Governor Romney the things that were important to him. And at the last moment he pulled out. So, this was in December of 2005, I believe.

CURWOOD: You're telling me that Governor, Mitt Romney, at the very last moment he yanks the rug out from under this project.

CASH: He did, he did. And I never talked to him about it. So I don't know what his motivation was, what his interests were. But that's the path that that he put us on is pulling us out of it.

CURWOOD: I imagined that the big fossil fuel interests weren't so crazy about this. And maybe he was thinking about the White House.

CASH: Uh, that's, that's possible.

CURWOOD: So, then how did RGGI come to being in Massachusetts?

David Cash is a former energy and environment commissioner for the state of Massachusetts and is the current dean of the McCormack Graduate School at UMass Boston. (Photo: Courtesy of UMass Boston)

CASH: So, we continued monitoring the other states after they started. Everybody but us signed an MOU, a memorandum of understanding between the states. Because at this time, the federal government was not stepping up. This was in the George W. Bush years, there wasn't a lot of activity on climate change. And as Governor Pataki noted, in his invitation letter, if you can't do this federally, regionally is much better, right. The larger the region, that market I described, works much better and lowers prices much better. And, uhm, so we waited and waited and, and then Governor Patrick was elected, I was lucky enough to make it through the transition and be bumped up to be Assistant Secretary for Policy in what became the new Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs with the idea that how could you regulate and have policies about energy and not have environment at the table and vice versa, right. And so we fully briefed him on all of the data, all of the models, all of the outputs from the whole RGGI process. And of course, he was interested in emissions, he was interested in health impacts, and he was interested in bill impacts. And we had the data that showed, as I described, with the auctioning and the reinvesting of that, those funds into energy efficiency, where we're going to lower bills. So, on day seven of his administration, he announced that he was joining and in fact, he did it on this campus at UMass Boston. It was quite remarkable.

CURWOOD: Now, David, the RGGI program itself, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, is, well, it's pretty invisible...

CASH: Mm, it is.

CURWOOD: ...to people on the street. Somebody who pays money to electric utility, for example. What does it mean for people, though, in their day to day life?

CASH: It means that they're going to get notices from their utility that they wouldn't have gotten before. A notice that says, hey, do you want a free energy audit of your house? And once we determine what your needs are in your house, do you want free light bulbs. You'd notice that your utility would offer to pay a large percentage of getting your house weatherized. You'd know that you could get a zero percent financed new natural gas furnace, or the newer kinds of electric heating and cooling devices that are way more efficient than air conditioners, and the old baseboard heaters that you remember. Those are all things you'd never see RGGI on it. You'd never see that this is a complicated policy, but you would see 'Oh, I have the opportunity to do this.' Or you would notice that your neighbor is working at a startup in Cambridge, or in Springfield or in Pittsfield. And, why are they in a startup? Because the market incentives are there for a lab researcher to start to try to make the new battery or the new photovoltaic cell or the new kind of electric vehicle. And then you might notice that your neighbor has solar panels on their roof and you go over to them and you say, 'Hey, What's that on your roof? I didn't know you're a Greenie.' And they'll say 'I'm not a Greenie. I just knew that if I put these on my roof, I was gonna not pay electric bills forever!' And then you're like, 'Oh, how do I do that?' That's how you would see it day to day, I'd see these changes happening in our society, and in how we buy energy and use energy in ways that are really profound.

CURWOOD: So, David, looking back to the launch implementation of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, which you participated in. Tell me a story of when you got either really excited or you were really surprised by what was going on? What was that aha moment?

CASH: Well, I think as someone who was, again, part of a team, in some ways, stretching to do something that hadn't really been done before. When the first numbers started coming in, of what revenues the states are getting, and how much it was saving consumers. When those numbers first started coming in. It's like opening up a champagne bottle at the at the end of a of a championship game. You know, like, yeah, we've- this is what we strived for. This is what we worked for. This is what our theory said would happen. But, wow! We made something work that could be a model for other jurisdictions. We made something work that was impacting people's lives in really powerful ways that they might not ever know about. We realize that they were low income families whose electricity budget which is a much bigger part of their family budget than for middle income and high income, that slice of their budget was relieved so they could spend more money on health care, on food. Those kinds of realizations when the when the when the numbers started coming in. That was pretty remarkable. And the fact that this just continued on that trend. I mean, this is- this has staying power.

CURWOOD: David Cash is a former environmental and public utilities commissioner in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He's currently Dean of the McCormick Graduate School Policy and Global Studies at UMass Boston. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today, David.

CASH: It's been a pleasure, Steve.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth