The Reindeer Chronicles: Working with Nature to Heal the Earth

Air Date: Week of December 18, 2020

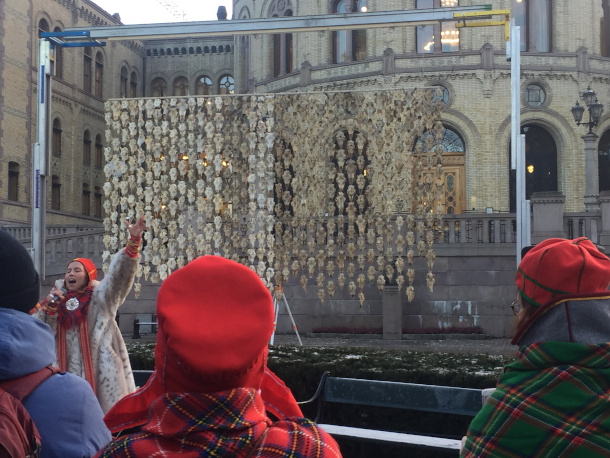

A protest in front of the Norwegian Parliament. In the background is an art piece consisting of 400 reindeer skulls, created by Màret Ánne Sara. (Photo: Astrid Carlsen (WMNO), Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY 4.0)

Environmental destruction and habitat loss can feel overwhelming, but the trend can be reversed. That’s according to environmental researcher Judith Schwartz. Her book, The Reindeer Chronicles: And Other Inspiring Stories of Working with Nature to Heal the Earth, details how people around the world are reclaiming land and helping mother nature heal herself. Judith Schwartz joins Host Paloma Beltran to talk about the restorative potential of landscapes and soils.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Environmental destruction and habitat loss can feel overwhelming but the trend can be reversed. That’s according to environmental researcher Judith Schwartz. Her book, The Reindeer Chronicles: And Other Inspiring Stories of Working with Nature to Heal the Earth, details how people around the world are reclaiming land and helping mother nature. The book’s title is inspired by a case from Norway where the native Sami people still herd reindeer just as they have for generations. The Norwegian government claimed the reindeer hurt the delicate tundra ecosystem, seen by many as a convenient excuse to remove the Sami people and access the rich mineral deposits beneath their land. But that claim contradicted indigenous knowledge about the important relationship between reindeer and their frigid habitat. For more I’m joined now by Judith Schwartz, welcome to Living on Earth!

SCHWARTZ: Thank you, Yeah, so this is a case that speaks to the importance of indigenous knowledge. So, you know, for thousands of years, Sámi reindeer herders have been moving their animals across the far north, and they have summer terrain, and then they have winter areas. So they move the animals to different spots depending on the season. So the Norwegian government was operating on the assumption that, "well, if there are more animals, well, you know, that's bad for the environment. So we need to ask or demand that these reindeer herders lower the numbers of reindeer." But the truth is that the way that the Sámi herders have been managing their animals, in fact, helps to maintain the tundra ecosystem. So here's how it works. So with the summer herding, the reindeer are browsing, they are nibbling at shrubs and small trees. And the reason that that's important is that the native heath, the kind of grassy areas that has a higher albedo, which means that it reflects the heat. However, these shrubs and trees, they have a lower albedo, which means they retain the heat. And you know, when they get established, that can heat up a whole microclimate. Okay, so that is adding heat to the landscape. But because the reindeer are nibbling at those plants, they're keeping them in check, so that they don't have that heating impact. And in the winter, the reindeer in large numbers are moving across the snow, and their hooves are pressing down the snowpack. And while that initially sounds like a negative thing, that Oh, no, the beautiful snow there, you know, they're messing that up. Actually, the snow had been acting as an insulator. So it was keeping the cold away from the, it was protecting the soil from the deep chill. But when the reindeer press down the snow, that means that the soil stays frozen, the permafrost stays frosty, so they are maintaining the cold. And that is important, especially in an area near the poles that is warming faster than other parts of the world. And research was done that found that, I think the research was done in Siberia, the way north of Siberia, that areas that had herbivores, plant eating animals on them in the winter, stayed colder, significantly colder than areas that had no animals on them. So often the assumption is that animals are harming the landscape. But we need to ask questions of landscapes that have always had animals on them, and what is the function of the animals in that environment?

Another art instillation of reindeer skulls, this one by Sami arts activist Máret Ánnesara. (Photo: Heinz Bunse, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: Definitely. And I mean, currently, the Sámi people are still struggling to keep their rights. Could you tell us a little bit more about what they're dealing with right now?

SCHWARTZ: Yeah, it's actually a huge challenge in that the area that the Sámi live, happens to be an area with great mineral wealth, and also an area that would give businesses access to energy resources. And it's also attractive for hydro power. So there is tremendous pressure on these people to give up the rights to their land. Or kind of open the door a little bit. And we know that when you open the door a little bit, then you know, your rights begin to erode. And that can happen very quickly. People I know in that region are really concerned about this.

BELTRAN: So by now we are well aware that enormous chunks of the Earth's environments have fallen barren, in large part to human industry. But in your book, you show how feasible It is, in many cases to restore biodiversity to devastated regions. What are the physical steps to achieve environmental restoration and how does it work?

SCHWARTZ: All right, well, the important thing to know is that all of our ecosystems are always in the process of change. So you have forested areas that are shifting between one level of succession to the next, everything is always in process because that's how nature works. So we can work with natural processes to repair ecosystems. So in the most basic sense, what you want to do when you have an area that is no longer functioning, no longer thriving, is to build biodiversity, build biomass, which is the amount of plant material and build soil organic matter. That is kind of the formula, because that is how our healthy ecosystems evolved through, over long, long periods of time. But working with natural processes, we can certainly nudge our landscapes in the right direction. And depending on where you are, it doesn't even necessarily take that long a time.

A Sami woman smiles at a reindeer. (Photo: charclam, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: Yeah, there definitely seems to be a lot of misunderstanding about how soil works, right. And there's a chapter in your book where you talk about female action, you form part of a group of women who wanted to learn how to be ranchers. And I found it fascinating that you talked about the connection to the land, how some woman might experience a stronger connection to soil than others sort of driving this movement. Could you maybe tell us a little bit more about that, and do you feel this strong connection to the land?

SCHWARTZ: Yeah, yeah. So when I wrote a book about soil, and I talked about it with other women, I was surprised by just how they kind of brightened up and they said, "Oh, my gosh, nothing makes me happier than having my hands in the soil," or they remember their childhood and how they played with plants and animals, but it was about a visceral connection to the soil. And in truth, I didn't originally have that, I came to an appreciation of soil through looking at how ecology works, and what the potential for restoring soil is. But I'm certainly learning and I'm certainly enjoying gardening. And I certainly enjoy looking at critters in the soil. So there is something, and actually when I do so, it brings back a kind of childhood sense of exploration and just that tactile, enjoyment of just being in a place. I just find that there are so many women that are doing this work, that have an intuitive connection to how everything links together, just a kind of like they get it immediately. And it was really exciting when I went to the new cowgirl camp in eastern Washington State. And there were a bunch of us all together that could just sort of be soil nerds and be animal nerds and talk about different breeds of sheep, and, you know, we can all laugh together and how silly these animals are, and it was really a wonderful thing. And what impressed me so much was that many young women just, they just felt so empowered about the notion of buying a ranch and managing animals, when I can tell you for certain that when I was in my 20s, I would never have thought that that was even within the realm of possibility. But it can be done. And that's the thing. We had sheep on our property a couple of years ago. And it just seeing those animals being around them learning their personalities, was so much more meaningful to me than I ever would have guessed.

BELTRAN: There's like no way of putting an actual economic value for our interaction with nature, right?

SCHWARTZ: That's true. And a lot of people I know, do this work on a shoestring and yet are among the most fulfilled, happy and engaged and optimistic people that I know, because they are doing what they love. And there is really nothing like being connected to landscape.

BELTRAN: Could you maybe talk about some of the problems in your book that you encountered or some of the problems that people were experiencing? that had to do with environmental restoration?

Dales Mountain Ranch in Washington, near the Colombia Gorge. (Photo: Unsettler/Eric Anderson, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

SCHWARTZ: As I was exploring in my own reporting many different ecological challenges and how they could be addressed, I kind of fell into the trap of thinking that all we needed was to know the science, all we needed was to know the techniques, the right way to do agriculture that would be regenerative as opposed to degenerative, and all of these different wonderful ways of restoring the watercycle etc. I thought that all we needed was just that knowledge, but when you come back to it, environmental problems are really people problems, in that it reflects the way that people have been managing these landscapes, often looking to extract value without kind of holding on to the the basic elements that provide function and value. So what I saw many times were challenges among people, communities that had a hard time working together, because each different groups within the community didn't understand what the other groups were doing. And in fact, in my reporting, I was able to, to observe an incredible episode where groups that had been in tremendous conflict were able to come to an agreement on how to work on their land. And also, sometimes the human side of where we get stuck relates to the legacy of industrial agriculture or the legacy of colonialism.

BELTRAN: Most people would think of restoration as a hard and slow process. But in your book, could you describe that once a project reaches a certain point, biodiversity is able to come back pretty quickly! Why do you think we lack an understanding on how biodiversity restoration works, and how is it able to come back so rapidly?

SCHWARTZ: Well, I guess it's worth appreciating that nature wants to heal. Nature wants to move towards a state of greater health and abundance. So in other words, we'd be working with that tendency that is already there. As for why we don't know this is possible, I think that we often kind of look from a problem standpoint that we kind of go along in thinking that things have always been the way they look to us right now, and then when something goes wrong, we react and try to scramble to solve a problem without necessarily really understanding the conditions that created that healthy landscape in the first place. Environmental restoration represents a huge opportunity. And I think we've missed opportunities in the past, when we have looked at climate as a matter of technology and the atmosphere, as opposed to understanding that what's in the atmosphere has moved through the ground and cycled through the ground as well. And by focusing on what we can do on the ground, by restoring our soil, rebuilding organic matter, drawing down carbon from the atmosphere, into the soil and vegetation, we have just so many possibilities that we've so far neglected. But we don't have to keep neglecting that, and I would say that there are signs that people are realizing that this is a very meaningful and, you know, optimistic way to go.

BELTRAN: Judy Schwartz is the author of the Reindeer Chronicles and Other Inspiring Stories of Working with Nature to Heal the Earth. Thank you for this beautiful book and conversation, Judy.

SCHWARTZ: Well thank you, my pleasure.

Links

Click here for more on The Reindeer Chronicles

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth