Florida-Sized Glacier Could Unleash 2+ Feet of Sea Level Rise

Air Date: Week of March 4, 2022

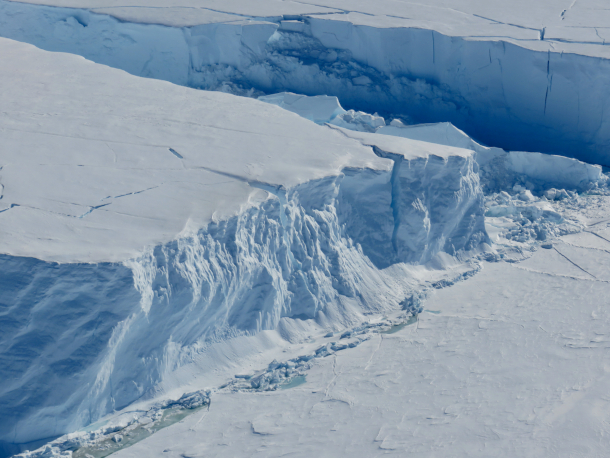

The Thwaites Glacier is one of the hardest to access places of Antarctica, and scientists have only recently been able to go to study the area on the ground. (Photo: Karen Alley)

Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica is one of the largest in the world, and scientists consider it the world's most important glacier, not just due to its size, but also because of the massive amounts of ice it is holding back behind it. Glaciologist Karen Alley joins Host Jenni Doering to explain how the melting and collapse of this glacier and the ice it holds back could affect sea levels in years yet to come.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Thwaites Glacier is one of the largest in the world, about the size of Florida. Should it melt completely it would raise sea levels around the world by something like two feet. But even that might be just a start. Some scientists suggest the loss of Thwaites from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could uncork even more massive amounts of ice behind it, and lead to many feet of sea level rise. And that is why some have dubbed it the "Doomsday Glacier. " Here to help us understand what’s happening to Thwaites is glaciologist Karen Alley. She’s an Assistant Professor in the Centre for Earth Observation Science, Environment and Geography at the University of Manitoba. Professor Alley, welcome to Living on Earth!

ALLEY: Thank you so much for having me.

DOERING: So I've been seeing the word "doomsday" all over the media stories about Thwaites Glacier. How accurate is that term? And how worried should we be that the glacier is on the brink of collapse?

ALLEY: So if you were to argue what is the most important glacier in the world, it would certainly be Thwaites Glacier. Thwaites is huge. It's a little bit bigger than the state of Florida. So this is a tremendously large tract of ice and it is retreating, it is changing very quickly, it is contributing to sea level rise, we expect it to contribute much more to sea level rise in the future. Doomsday depends on how you look at it. So it certainly is something that we need to be paying attention to. It is very important, it is changing, it is going to affect communities all over the world as sea level rise continues. But it's also something that we can learn about and prepare for. And these changes are going to happen on decades-to-centuries type timescales that give us the chance to understand what's happening, and to prepare for those changes that might occur in the future.

DOERING: There are of course, a lot of glaciers on Earth. So besides its size, what else makes Thwaites of special concern?

ALLEY: So, Thwaites Glacier sits at the outlet of a lot of the ice that makes up the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. And this ice sheet is special, A, because it's large, certainly, but B, because of the shape of the land that it's sitting on. So glaciers tend to be very stable and change very slowly, if the land that they're sitting on kind of slopes upward from the coast. But West Antarctica does the opposite. It gets deeper as you go inland from the coastline. And that's not a very stable configuration once you start having forcings that cause a glacier to retreat, if it has that kind of configuration, that kind of shape of its bed, it can get into a feedback loop that basically makes it really hard to stop once it starts. So this is a big glacier. It holds a lot of ice, but it's also in this unstable configuration, that we could push past a tipping point, depending on how we warm the earth in the future.

As Thwaites Glacier ice shelf breaks down and melts, it accelerates the melting of the ice behind it. (Photo: Karen Alley)

DOERING: Wow. So even if it is over decades or centuries, how much sea level rise are we talking about here?

ALLEY: With the contributions from Thwaites Glacier and the other glaciers that it will impact as that sea level rises, at maximum over the next few centuries, we'd be talking about a few meters of sea level rise. In the near term, that translates to centimeters to maybe tens of centimeters in our lifetimes. But those are numbers that are very difficult to predict with a lot of certainty. We kind of know the end state. We know that Thwaites could retreat all the way back to the Transantarctic Mountains. And in that case, we're looking at a few meters of sea level rise, but the pacing of that and the amount of that, in the meantime is very difficult to predict.

DOERING: So Dr. Alley, I live here in Boston, and today, it's in the 40s. We've had a lot of ice and snow on the ground recently, and it's all melting away. And it happens pretty quickly over the course of a day or two. It's really hard for me to picture it taking centuries potentially for ice, even this much ice to melt. How is it possible that it takes so long for this ice to melt on the earth?

ALLEY: I've been doing glaciology for quite a few years now. I've been to Greenland, I've been to Antarctica, I've stood on those ice sheets and even being there, it's hard to realize just how much ice there is. In Antarctica as a whole, it has about 57 meters of global sea level, I mean, just picture 57 meters. It's just a tremendous amount of ice. And so those sorts of changes, we're talking about changes that would be significant on a global scale. It just takes a while because there's so much ice there. It's also still quite cold in Antarctica. We are warming the world, for sure, we're warming the oceans, we measure it in the oceans and in the air temperature, but it's still very cold. So at Thanksgiving, if you have your turkey and you thaw it on the counter, it takes several hours to thaw your turkey on the counter, although there's you know, health risks with thawing it on the counter, I don't recommend it. If you thaw it in your refrigerator, it will still thaw but it'll take a lot longer. And we're thawing Antarctica in a refrigerator or in a freezer at this point. It's still a very cold place. But the warming is significant enough for us to be seeing those changes that really matter on a global scale.

Shown here is one of the camps during the 2019-2020 Thwaites-Amundsen Regional Survey and Network Integrating Atmosphere-Ice-Ocean Processes (TARSAN) project. (Photo: Karen Alley)

DOERING: So you mentioned Thwaites is already contributing to sea level rise. How much?

ALLEY: So, global sea level rise right now is a few millimeters per year, and Thwaites Glacier alone contributes about 4% of that sea level rise. So it seems like a really small number. Right now other ice sheets, the Greenland ice sheet and other glaciers contribute to that. We also are seeing sea level rise just because water expands when it gets warmer. So it's taking up more space, and that's causing sea level to rise. But this one glacier alone contributes about 4% of what we're seeing. And we do expect that percentage to increase in the future.

DOERING: So, what exactly is being researched at the Thwaites Glacier now, what are scientists still looking to figure out?

ALLEY: There are many aspects that we're still trying to figure out. And there are many different teams that are working on those very distinct aspects. So one thing we're definitely trying to constrain is what the ocean is doing. So the changes that we're seeing are most directly because of changes in ocean circulation and ocean temperature. And so we need to determine what those changes are, and explain why they have happened and how they're likely to change in the future. On the ice itself, we're measuring the ice shelf, we're trying to understand the structures of the ice shelf, and the dynamic processes that govern how it flows, so that we can understand its stability, and when it is likely to disintegrate. Then we move upstream, and we think about that area where it goes from sitting on land to going afloat. That's called the grounding zone. And there are really complicated processes with how the ocean interacts with the ice there and how the dynamics, the physics of the ice works with the grounding stone. And even upstream above that, there's a lot we don't know about what the bed is like that the glacier is sitting on. So we need to determine how it behaves, if we're going to be able to predict how the grounded ice, the ice that sitting on land, is going to respond to these changes in the future.

DOERING: Professor Alley, what do you want the public and policymakers to understand about Thwaites?

Karen Alley is an Assistant Professor in the Centre for Earth Observation Science, Environment and Geography at the University of Manitoba. (Photo: Cecelia Mortenson, Courtesy of Karen Alley)

ALLEY: First of all, there's a lot that we still don't know about Thwaites. We're doing our best, we definitely know the direction things are going. Thwaites is retreating, Thwaites is contributing to sea level rise. We don't yet know for sure, if we've kind of pushed it over a tipping point. There's a chance, if we can keep warming down so that it doesn't get too high, that Thwaites might not retreat all the way. And so being proactive about global climate policies is really important. It may keep Thwaites from retreating all the way. Even if we do cause Thwaites to retreat, it will take a while for that sea level rise to become really large. It's already happening. I call sea level rise a 'here-and-now problem' because there are already coastal communities being impacted by sea level rise. But those impacts are going to get much larger in the future, even if we don't push Thwaites over a tipping point. But it's really difficult to think that far in the future as policymakers, right? It's hard to plan that far in the future. But it's something we have to do. It's something that we know is coming. And so it's something we need to start thinking about responding to now. Or we're going to see really huge impacts, which we're already starting to see, particularly on vulnerable communities that live in coastal regions.

DOERING: Karen Alley is an assistant professor in the Center for Earth Observation Science, Environment and Geography at the University of Manitoba. Thank you so much, Dr. Alley.

ALLEY: Thank you for having me.

Links

The International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration website

More about Professor Karen Alley

Click here for a 2021 paper co-authored by Professor Alley on Thwaites

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth