Nations Vow to Curb Plastic Waste

Air Date: Week of March 11, 2022

Located outside of the venue that hosted the UNEA meeting, this sculpture by Benjamin Von Wong suggests that the world must turn off the “tap” on plastics. (Photo: UNEP/Cyril Villemain, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

At a recent UN meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, delegates from over 170 countries committed to come up with an ambitious cradle-to-grave, legally binding agreement to tackle the international plastic pollution crisis. Maria Ivanova served as part of the Rwanda delegation to Nairobi that successfully advocated for this ambitious approach and joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss.

Transcript

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB:And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The United Nations Environment Program recently wrapped up five days of negotiations in Nairobi, Kenya. Representatives from over 170 countries committed to come up with an ambitious agreement to tackle the international plastic pollution crisis. The world currently produces roughly 300 million tons of plastic each year and just a tiny fraction of it gets recycled. In Nairobi delegates agreed to a cradle to grave, legally binding approach to stem the flow of plastic waste. The resolution has been lauded as the most important environmental multilateral agreement since the Paris Agreement. Maria Ivanova is an Associate Professor at University of Massachusetts Boston and she served as part of the Rwanda delegation to Nairobi that successfully advocated for this ambitious approach. Maria Ivanova, welcome to Living on Earth!

IVANOVA:Thank you.

BASCOMB: So going into this meeting, there were three different options on the table. One was to just tackle single use plastic, another would only address the waste problem in the oceans, and the third was a full lifecycle approach, which is ultimately what was agreed upon here. Briefly, can you remind us, what is a full lifecycle approach? What does that mean, exactly?

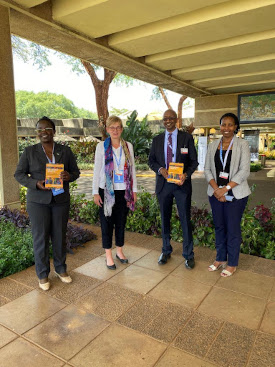

Rwanda and Peru’s ambitious resolution for an international legally binding treaty on plastic pollution was ultimately chosen by representatives at the UNEA meeting. The Rwanda delegation from left to right: Her Excellency Dr. Jeanne D’Arc Mujawamariya–Minister of the Environment, our guest Maria Ivanova–Associate Professor of Global Governance and Director of the Center for Governance and Sustainability at UMass Boston, His Excellency Dr. Richard Masozera–High Commissioner of Rwanda to Kenya, and Juliet Kabera, Director General of Rwanda Environment Management Authority. (Photo: Maria Ivanova)

IVANOVA: A full lifecycle approach is thinking, in a sense, from cradle to grave. It's thinking about a product, from the imagination of what that product will look like, its design, the extractions of the materials, and the production of the product, the use of that product, and the disposal. So the full lifecycle is a simple cradle to grave approach. And for plastics that is very important.

BASCOMB: So this is a resolution to begin negotiating a legally binding treaty. How might that actually be applied in this context? And why is it significant?

IVANOVA: A legally binding treaty is significant, because it provides for accountability measures. This was the most ambitious option on the table, championed by Peru and Rwanda. And so for all countries to agree on a legally binding treaty, meaning that they would be accountable for whatever they do, is very significant, because it will set a regulatory framework that will enable governments to put necessary regulations in place and legislation. But it would also provide a level playing field for businesses that can start innovating. There were a number of businesses represented in Nairobi, including Dow Chemicals, the American Chemistry Council, and others. There was no pushback against the treaty. Indeed, business welcomes an international legally binding treaty, because it will provide the predictability that business needs. This harkens back to the Montreal Protocol, that regulated substances that deplete the ozone layer. It's a very similar setting, that in the Montreal Protocol, governments agreed to regulate those industries. And that led to the development of substitutes. And DuPont was the company that emerged as the champion, because there was a predictable, consistent, constant regulatory framework. So we're seeing a similar dynamic here, even though plastics is a much more difficult problem to tackle, at least at this point.

Our guest Maria Ivanova was honored to be part of the Rwanda delegation, which saw tremendous success during the UNEA negotiations. (Photo: Maria Ivanova)

BASCOMB: So it makes sense, then that companies would want certainty, they want to know if I make a product, I can sell it just as easily in the United States as I can in France as I can in Argentina, because everybody has agreed that this is acceptable.

IVANOVA: Indeed. The issue with plastics is that there are so many ways to make plastics. And there are so many additives, so many chemicals, and so many ways to recycle or not recycle plastics. There are also various ways to substitute for plastics. And I think an international legally binding treaty would enable innovation in this space. And this is what we have seen in Rwanda already, which is a country that has banned plastics, first plastic bags in 2008, and then all single use plastics in 2019. And you've seen how various companies have entered that and come up with substitutes for the plastics.

BASCOMB:So the negotiations will take place over the next two years. And of course, the devil is in the details with these types of things. How confident are you that all of these countries will come together and act in good faith to really address the plastic problem? And not, you know, ultimately try to water it down for reasons that might serve their own self interest?

The president of the United Nations Environment Assembly brings down the gavel as the resolution for an international legally binding treaty is officially passed. (Photo: UNEP, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

IVANOVA: That's a difficult question. As you know, with every negotiation, there are a number of interests at play. And we want to see countries commit. And we want to see them deliver on these commitments. It was inspiring to see that happen in Nairobi. And I do want to see that happen over the next two years, and indeed over the next four years as this treaty is being developed. However, governments change. We are in a crisis of multilateralism at the current moment. And we don't know what these commitments will be. Therefore, I think this process opens the space not only to governments that have ambitions but also to civil society, and to businesses, and to academia.

BASCOMB: So nobody quite expected the United States especially to sign off on this, and a legally binding agreement. The US is of course, the largest user of plastic per capita in the world. My understanding is if they sign up on a legally binding treaty, they can be sued domestically for not living up to their agreement. And you are, of course, part of the Rwanda delegation that made this happen. What was in the secret sauce? How were you able to negotiate this and have such success here?

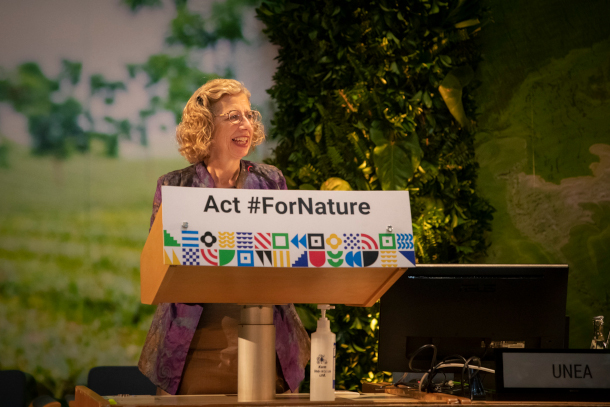

Inger Anderson, the Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme, called the resolution “the most important international multilateral environmental deal since Paris,” referring to the 2015 Paris Climate Accord. (Photo: UNEP, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

IVANOVA: I have to say that the US delegation came willing to resolve the problem. There was no reticence on behalf of the United States of saying no, we cannot do this. On the contrary, the United States sees the problem. It sees the incredible opportunity for innovation and was ready to negotiate along with all other countries. So the US delegation was outstanding in its negotiation skills, but it was not pushing for a lowest common denominator. It was not, which was a refreshing sight to see, because we have seen the United States within the past administration pull out of international agreements that the US had already signed, right? And this is to see the United States in a leading position in negotiating an international treaty alongside with two small states, Rwanda and Peru, was really inspirational.

BASCOMB: Well, that is wonderful to hear. And ultimately, what will success look like to you when two years have passed?

Negotiations for an international treaty focusing on the full life cycle of plastic will take place over the next two years. (Photo: UNEP, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

IVANOVA: So, success will have many phases. Success will be to have an international agreement, signed, sealed, delivered, but ultimately, success will be when that agreement is implemented. And that kind of implementation can start now with various voluntary approaches that are already taking place. Those should not cease just because we have a process for an international legally binding treaty, they will continue. And I think that they can set the ambitions even higher and higher. But the kind of treaty that we're looking at will allow countries to develop their own national plans of how to deal with plastics. And to me success will be when we're not looking at a race to the bottom, but a race to the top. Which countries will have the most ambitious plans, which countries will have the most inclusive participation in those, and who will hit the targets first? That to me will be the successful, I wouldn't even say conclusion, but implementation of this treaty, because we will not implement this once and for all, this is a big issue. We see plastics are everywhere, and they're necessary, but we have to find a way to deal with them in a way that does not harm human health and planetary health.

Delegates from over 170 countries came together to discuss global plastic pollution at the fifth session of the United Nation Environment Assembly meeting in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo: UNEP, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Maria Ivanova is an Associate Professor of Global Governance and Director of the Center for Governance and Sustainability at UMass Boston and a member of the Rwanda delegation. Maria, thank you so much for taking the time and for all of your hard work on this issue.

IVANOVA: Thank you.

Links

UN Environment Programme | “What You Need To Know About The Plastic Pollution Resolution”

The Standard | “Meet Wong, Artist Behind Plastic Sculpture at UN Office In Nairobi”

UN Environment Programme | “Fifth Session of the UN Environment Assembly”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth