Record Heat Wave in Antarctica

Air Date: Week of March 25, 2022

Around the March Equinox in 2022, parts of Antarctica were seeing temperatures spike to nearly 70 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than average. (Photo: Christopher Michel, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

During the March equinox in Antarctica, the eastern portion of the continent recorded temperatures around 70 degrees Fahrenheit higher than typical. At the same time, the Arctic also boasted higher-than-average temperatures. Climate scientist Zeke Hausfather joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss what these heat waves mean for global climate change.

Transcript

CURWOOD: March 20th marked the most recent equinox. That’s when the sun appears to be directly above the equator and shines equally on both polar regions. But this time both the Far North and Far South also shared some record heat waves. As summer was ending in the Antarctic, some weather stations there recorded several days at 10 degrees Fahrenheit. Now that might seem quite cold to us, but it’s a whopping 70 degrees warmer than seasonal norms, and a huge surprise to scientists. And at the same time portions of the Arctic had some days that were more than 50 degrees warmer than usual, though far Northern heat waves are not as uncommon these days as this recent far Southern one. To find out what might be going on, we called up Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist and climate research lead at Stripe Climate. His company is looking at ways to finance and build systems intended to remove massive amounts of carbon from the atmosphere and thereby reduce the impact of global warming. He’s on the line now from Oakland California. Zeke, welcome back to Living on Earth!

HAUSFATHER: Thank you. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: So tell me what do climate scientists and meteorologists think is happening in Antarctica to start up this specific heat wave.

HAUSFATHER: So what's happening in Antarctica is, to be honest, mind boggling for us, you know, it's 70 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than it should be for this time of year in parts of eastern Antarctica, which is really unprecedented. We've never seen anything like this in the 70 years of data we have from that region. We're working, as we speak, to figure out, you know, what role climate change played in this, how much more likely this sort of heat wave was made by the warming that we've experienced there in the world? And we know that, you know, warming has certainly contributed to these sort of extreme heat events, but exactly how much is something we're gonna be figuring out using both the data we've collected over the years and our climate models.

CURWOOD: Now, the southern hemisphere has a lot of heat problems in Australia. Any relationship, do you think, to what's going on in Antarctica?

HAUSFATHER: So certainly, both are being exacerbated by a common cause, which is the the warming of the planet, you know, we've seen around the world, these sort of extreme heat events becoming more common. Another great example is what we saw in the Pacific Northwest this past summer, you know, we had 116 degree temperatures in Portland, 121 degree Fahrenheit temperatures in Canada. And we actually took a look, we being climate scientists took a look after that event. And what we found was quite interesting, you know, it was still an extremely rare event, a maybe one-in-1000 year event. But without climate change, it would have been a one-in-150,000 year event, so already has been made 150 times more likely. And if the world warms by two degrees Centigrade, about four degrees Fahrenheit, by the end of the century, which we're on track to warm more than that today, it would become a one-in-20 year event. And so that teaches us that, you know, this larger global warming can have a disproportionate impact on the likelihood of these sort of extreme heat events.

????Heat wave in Antarctica, +38 °C (+68 °F) above normal.

— Dr. Robert Rohde (@RARohde) March 21, 2022

That's not an error, or a typo.

The remote research station at Dome C recorded a temperature nearly 40 °C above normal for this time of year, beating the previous March record by a startling 20 °C. pic.twitter.com/HkzydQyQ7A

CURWOOD: To what extent, is there's some sort of atmospheric river bringing water vapor down into Antarctica from places that usually doesn't get it?

HAUSFATHER: So, any extreme heat event is going to have meteorological conditions or weather patterns that are driving it. And so in this case, what seems to have happened is there was an atmospheric river that brought a lot of moisture over East Antarctica. And that moisture carried a lot of heat with it. And so that drove these extreme temperatures we've been seeing in the region. Or relatively extreme, I should say, it's still below zero, but it's not negative 70. And so that, you know, there was a direct cause of that. But that sort of event, you know, has not happened in the past, you know, we have nothing similar to it in the seventy year record we have for that region.

CURWOOD: So this particular heatwave in Antarctica, how fair is it to attribute this to global climate change that humans are involved in?

HAUSFATHER: So we know that climate change has made Antarctica warmer than it was a century ago. You know, Antarctic is actually a fairly complicated place when it comes to the climate, in part, because there's really two factors going on. One is greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which are warming the region. But at the same time, the ozone hole that we created through emissions of chlorofluorocarbons back in the, you know, 60s 70s, and 80s, has actually led to a lot of cooling in that region relative to what would have happened if we hadn't emitted those. And so because of that Antarctic has warmed more slowly than the Arctic. You know, that being said, it's still warmed enough that there's probably, you know, an influence in terms of the likelihood of the sort of extreme heat event. It's not warming as fast as the Arctic, which is warming about three to four times faster than the rest of the world, in part because one of the big drivers of Arctic heating is what we call albedo, or reflectivity changes. So as you melt sea ice, you melt snow, you expose dark surfaces underneath, those dark surfaces absorb much more of the sun's heat, and reflect much less back to space, Antarctica is a bit more resilient for that, in part, because so much of the continent is covered by mile thick ice sheets that you need a lot of melting to expose darker surfaces. So in part, because of that, we haven't seen quite the degree of amplification of global warming in Antarctica, as we've seen in the Arctic, there's also the possibility and this is an area where, you know, it's a little harder for us to be sure about, that climate change is changing weather patterns in a way that might make this sort of event more likely. But again, until we have time to, you know, do research on this, do attributional studies of this, it's, we can't say with confidence today exactly how much more likely climate change made this sort of extreme heat.

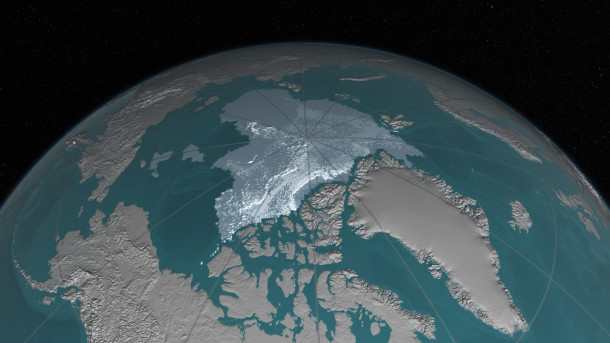

Scientists have estimated that the Arctic Circle is warming from 2-4 times as fast as the rest of the world, causing permafrost to thaw at a rapid rate, impacting infrastructure and people’s livelihoods. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Tell me, how does climate modeling work when it comes to figuring out possible extreme weather events?

HAUSFATHER: Sure. So you know, what we saw in Antarctica is an interesting example, right? It's so far outside anything that we've observed in that region, that we can't easily use the historical temperature record there to figure out, you know, what are the odds of this sort of event. And so for that climate models are actually really useful. And in particular, a fairly new development in the climate modeling world called large ensembles are really useful. And the idea behind large ensembles is you take a state of the art sort of supercomputer climate model, and you run the same model, say 50 different times. But each time you start it up slightly differently. Of a butterfly flap its wings in Brazil, so to speak. And that leads to you know, different chaotic weather patterns in each of those model runs. And so you can look across, say 50 different versions of the world with slightly different weather and say, do we see anything like what we saw this past week in Antarctica in any of those models. And it turns out some initial work being done by Flavio Lehner at the National Center for Atmospheric Research shows that we do. There is a particular member of that ensemble that has a sort of crazy extreme heat spike in 2018 in that model run. That’s similar to what we saw in the real world in 2022. And so we can look at that and say, okay, given these 50 versions of the real world we see this one time, what does that tell us about the odds of this event? And then what we can do, which is really cool, is we can sort of say, okay, let's go back in time in those models to say, or the 1800s in general and say, okay, in the climate of the 1800s? How likely would this event have been? And we can look at the difference between that likelihood to get some sense of how much more likely climate change has made these sort of extremes. So a really cool way to use climate models to sort of study how the variability of weather and the likelihood of extreme heat events has changed.

Antarctica is not warming as fast as the Arctic, in part because of a feedback loop in the Arctic, where the thinner ice melting faster reveals dark open water, which absorbs sunlight and traps more heat. In contrast, Antarctica has much thicker ice sheets, so most of the melting has yet to reveal the dark open water. (Photo: Jeremy Potter, NOAA/OAR/OER, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Okay, I'm sitting down. Now, Zeke, just tell me what sorts of predictions are the climate models showing us now in terms of extreme weather events going forward?

HAUSFATHER: So it really depends on what we do. If we can bring our emissions down to zero, the Earth will stop warming, we're still going to be stuck with the warming we've had so far, at least unless we're removing carbon from the atmosphere. But we can ultimately control how much warming we have. That said, the world today seems on track under current policies for about three degrees warming, by the end of the century, three degrees centigrade. So about five, five and a half degrees Fahrenheit, that could be much higher, if we end up getting unlucky with what we call feedbacks in the climate system, or could be a little lower if we end up getting lucky, but it's still a very scary future. You know, one of much more extreme heat events, more extreme wildfires, sea level rise, many of the world's species going extinct because the temperature ranges they live in are shifting faster than they can move, impacts in agriculture. You know, they're sort of a parade of horribles so to speak, that would happen in that world. But the good news is, we can change that, you know, we still have time to reduce our emissions. And if we get our emissions globally to zero, in the latter half of the century, we could still limit warming to well below two degrees, which is what countries agreed to under the Paris Agreement back in 2015.

CURWOOD: So, Zeke, you're a scientist, but I'm going to ask you a political question. Right now, with the war in Ukraine, and with the boycott of Russian oil, there's a lot of talk of building out more fossil fuel infrastructure. How advisable do you think it is that we should add more infrastructure for fossil fuels to meet the problems that have been caused by this unprovoked attack on another nation by the President of Russia?

Zeke Hausfather is a climate scientist and Climate Research Lead at Stripe. (Photo: Courtesy of Zeke Hausfather)

HAUSFATHER: It's a tough question. I think we need to be very careful about locking in further dependence on fossil fuels, given the challenges of climate change, and the big impacts it's going to have on the world. You know, at the same time, high fuel prices fall mostly on the poor. Lower income people spend much more of their paychecks on transportation, they tend to have older, less efficient cars. And so I think we need to target our climate policies in a way that really helps the poorest people. You know, electric vehicles are great, it's great, they've been getting a lot cheaper, as someone who drives an electric vehicle, you know, I don't pay that high cost of the pump. But electric vehicles are new cars, and most people who are lower income, don't buy new cars, they can't afford to. And so having ways to give relief to those people in the short term, I think is important to consider. At the same time, we need to make sure that any additional oil and gas infrastructure we build, you know, is built with a view toward eventually getting off it. You know, if we're building liquefied natural gas terminals to bring more gas to Europe, we should make sure that those could also support liquefied hydrogen for a future green hydrogen economy. You know, we need to make sure that pipelines we're building to transport natural gas, say from the Middle East or from Africa to Europe could potentially take CO2 in the future to places to sequester and underground you know, any of the future fossil fuel infrastructure we build we need to build with an eye toward repurposing it for the clean energy economy in the future.

CURWOOD: Zeke Hausfather is the Climate Research Leader at Stripe. Zeke, thanks for taking this time with me today.

HAUSFATHER: No worries. It's great to chat.

Links

NBC News | “Antarctica, Arctic Undergo Simultaneous Freakish Extreme Heat”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth